Though the current rankings in Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros have a few mild surprises (Washington, D.C. tops the list, with New York and Chicago in second and fifth place, respectively), the chart in the report — by Christopher B. Leinberger and Patrick Lynch from the Center for Real Estate and Urban Analysis at George Washington University School of Business — that will either buoy or dismay pedestrians and density advocates alike is the one that predicts the future of walkable urbanism in those same areas. But wherever your city ranks on the list, if you’re an urbanist, you’ll love at least one Leinberger forecast: “Top-ranked walkable urban places are witnessing the end of sprawl. This is a major change in the way we build the country.”

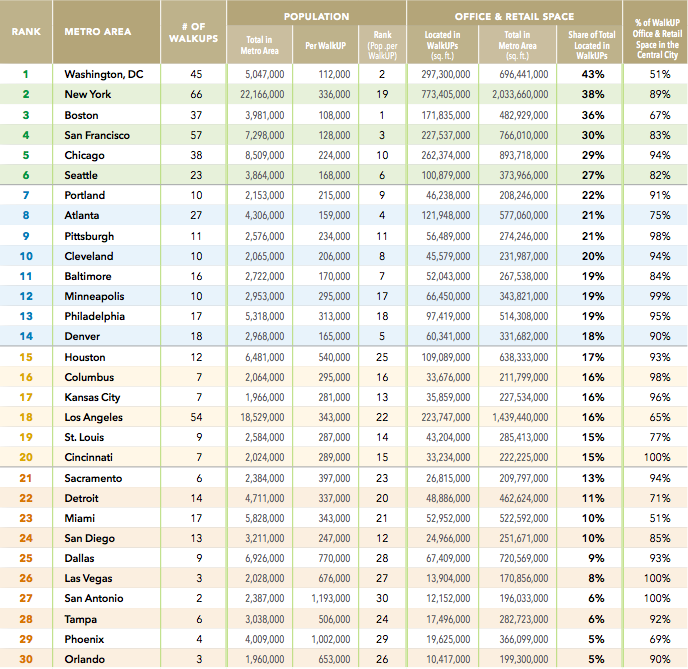

Leinberger and Lynch’s operating premise is that Americans with options are increasingly moving away from what they call “drivable sub-urban” in favor of walkable urban places, which they call WalkUPs — basically, places where offices and stores are walking distance from homes and where those spaces are beginning to fetch higher rents because of demand. With that understanding, the report’s current ranking divides the 30 largest metro areas, from top to bottom, into four sections: high walkable urbanism, moderate walkable urbanism, tentative walkable urbanism and low walkable urbanism:

A current ranking of walkable urbanism in America’s 30 largest metros, from “Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros” © The George Washington University School of Business 2014

Fear not, No. 23 Miami. A look at the metrics behind the list reveals advice for metros looking to move up: Take seriously the movement toward the urbanization of suburbs, plan for transit development, and be friendly with your zoning.

Urbanizing suburbs are a huge factor pushing D.C. into its top spot: “It not only has the most office and retail in WalkUPs, but also has the most balanced distribution of walkable urban space between the central city (51 percent) and suburbs (49 percent).

Chicagoland, on the other hand, has some things to learn. “Chicago’s doing a lot of things right but it’s focusing on center city, but very little in the suburbs,” explains Leinberger. “Evanston is kind of lonely out there.” Meanwhile, he points out that a bright spot for Detroit is “a remarkable turnaround in suburban town centers, as well as unexpected turnaround in downtown and midtown.”

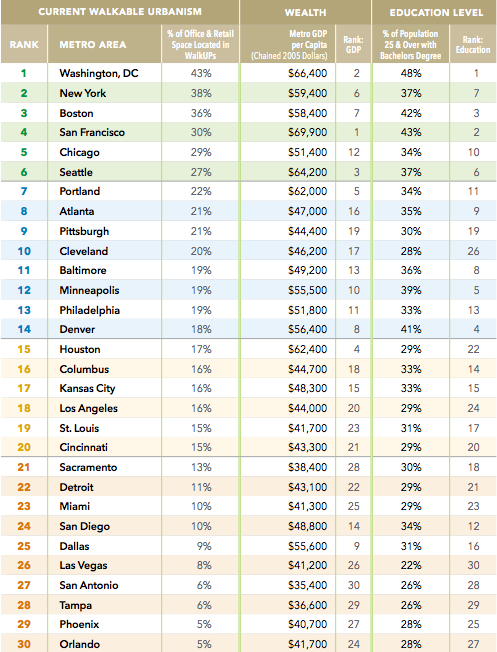

In the future rankings (with three levels: high potential for future walkable urbanism, moderate potential for future walkable urbanism, and low potential for future walkable urbanism), Detroit’s high marks for WalkUP development, and Denver’s rail investment earn the former a jump on the list of more than 10 points, and the latter a move from No. 14 to No. 9.

A prediction about the future of walkable urbanism, from “Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros” © The George Washington University School of Business 2014

“It’s not essential to have light-rail transit, but it sure does help,” Leinberger says. “[But] there are great examples of WalkUPs that just have bus and bike and car access. Bike lanes are cheapest way to increase your transportation options.”

When it comes to zoning, Leinberger looks around the U.S. and sees local politicians and their constituents warming to the idea of using less land and getting more out of existing infrastructure. He should know. Leinberger is also the president of Locus, a coalition of real estate developers that works in concert with Smart Growth America to promote policies that enable denser, transit-oriented communities. “As a real estate developer, I’ve done 12 projects, all walkable urban places, and all of them were illegal when I proposed them. That gets tiring,” he says.

Both the current and future rankings recast decades-old city vs. suburbs tension and suggest that, for the best possible economic outcome, a region’s local governments and community groups need to pull together around development. Of course, this dream world would benefit developers (projects would be approved more quickly and built more cheaply), but it’s also a world, says Leinberger, where people want to live. “Blame the kids,” Leinberger says. “The millennials are driving this.”

Linking walkable urbanism to education and wealth, from “Foot Traffic Ahead: Ranking Walkable Urbanism in America’s Largest Metros” © The George Washington University School of Business 2014

Although more research needs to be done to understand why walkable urbanism is correlated with higher per-capita GDPs and education levels … evidence suggests that encouraging walkable urbanism is a potential strategy for regional economic development.

Leinberger says organizations like Locus and private real estate developers think constantly about affordable housing, and he seems confident that good solutions will come as walkable urbanism moves out of its infancy. He says he can name at least 14 affordable housing tools, such as federal low-income housing tax credits, but stresses that to develop a conscious strategy, “you have to have the intention to address it.”

Whether a region aspires to No. 1 on the list or keeps driving along at the bottom, pent-up demand leading to what Leinberger says will be “tens of millions of square feet” in urban development over the next decade” may force all metros to re-think how they’ll get a piece of that walk-in business.

You can read the full report, which includes methodology, here.

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Janine is a Philadelphia-based freelance writer and editor.