Urban Nation is an occasional column by Harry Moroz, NAC’s federal correspondent, on the latest urban-related policy issues in Washington.

Much has already been made of Mitt Romney’s accurate assertion that, “Forty-seven percent of Americans pay no income tax.” But the conclusion that the presidential candidate drew from this statistic — “And so my job is not to worry about those people. I’ll never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives” — is so bizarre that discussing why this 47 percent does not pay taxes deserves further explanation.

Indeed, Romney’s conclusion should be particularly troublesome to Next American City readers because it breathlessly sweeps aside good public policy that helps, more than anyone else, low-income metropolitan households.

As we know by now, most of the households in Romney’s 47 percent do pay taxes of some sort. Still, of those which paid no federal income tax in 2011, about 15 percent (11.5 million or so households) were exempt because of the earned income tax credit, the child tax credit and the child care tax credit.

The earned income tax credit (EITC), in particular, is an extraordinary benefit to cities and metro areas. Begun in 1975, the credit reduces the income tax liability of low- and moderate-income working households and, because it is refundable, provides a subsidy to households with sufficiently low income.

As the Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program has documented, the EITC does a very good job of targeting assistance to areas of poverty, and has continued to do so even as poverty has shifted away from urban and to suburban areas. Brookings researchers found that 60 percent of EITC funds went to residents of the 100 largest metros, while the credit grew most quickly in the suburbs where there were more low-income households.

Digging deeper into the program’s benefits, Brookings’ Alan Berube argues that the ETIC is both an anti-poverty program and a federal investment in local and regional economies. He points out that:

In 2004, the Community Development Block Grant and HOME programs…awarded roughly $3.1 billion to nearly 1,000 municipal governments nationwide. That same year, residents of those same cities and towns received over $20 billion from the EITC.

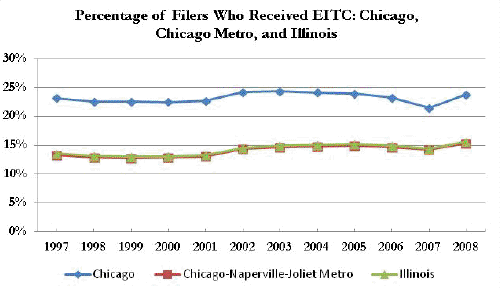

Take Chicago, for example. Between 1997 and 2008, the percentage of tax returns filed in Illinois which received the EITC benefit hovered around 15 percent (the percentage was nearly identical for returns in the Chicago-Naperville-Joliette metro). In Chicago proper, however, this percentage was significantly higher, at 25 percent of all filers.

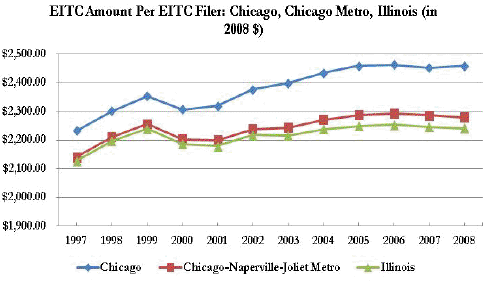

A similar story appears when looking at the EITC benefit amount per EITC filer. The EITC benefit was $2,239 per EITC filer in Illinois as a whole, while it was a significantly higher $2,458 per EITC filer in Chicago. The amount received per metro filer was also higher than the state amount.

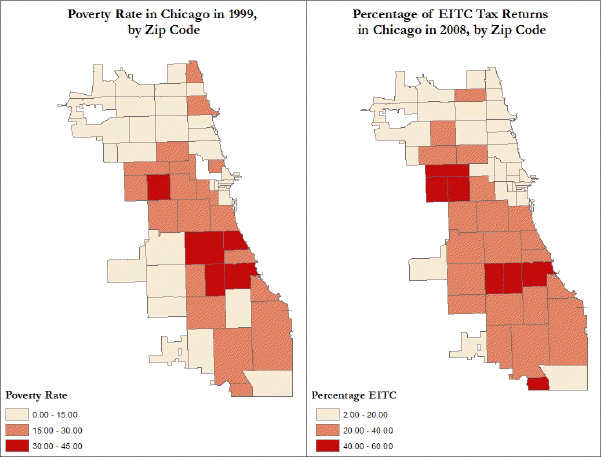

Finally, the EITC isn’t just good at targeting areas of need across cities and metros. As the maps below make clear, the EITC is also a hyper-local investment, targeting disadvantaged neighborhoods; the percentage of returns receiving the EITC roughly maps zip codes with higher poverty rates.

Note: O’Hare is excluded and poverty rates are approximated by zip code tabulation areas, which do not always match zip code areas. Source: City of Chicago and U.S. Census

But Romney’s dismissal of the 47 percent of Americans who do not pay taxes isn’t dismaying merely because it rejects a policy that is important to metro areas. The dismissal is so disappointing because it ignores the substantial benefit that not paying taxes brings to the low-income households in those areas.

First, by tying the benefit to having income, the EITC does a very good job of incentivizing work, particularly for single mothers. Second, the rudimentary understanding that many households have of exactly how the program functions may mean that it does not result in attempts to game the system by working additional hours to earn a larger benefit.

Importantly, the jobs that recipients of the EITC find are not “dead-end” jobs, but seem to result in earnings growth in the future. Additionally, the EITC is particularly effective at helping the transient poor — that is, poor households which move in and out of poverty because of short-term disruptions in income. The EITC avoids the substantial costs associated with these households falling permanently into poverty because of a one-time event like a health crisis.

Further, a study of how the EITC was used in Chicago found that households used the credit to satisfy current consumption needs, but also to make expenditures associated with social mobility. In direct contradiction of Romney’s assertion, the researchers conclude that:

[T]he EITC appears to be our most effective federal program for leading low-income families on a path toward true economic independence.

The benefits of the EITC don’t stop with current workers, however. Recent research shows that receipt of the EITC improves the health outcomes of children. Another paper used the EITC to examine the causal impact of income on educational outcomes (math and reading test scores), and found that “extra family income has a modest, but encouraging, causal effect for children growing up in poor families.” In other words, give families more income and math and reading test scores will rise.

The very design of the EITC — the fact that it provides more income to low-income households by reducing and eliminating their tax burden — is probably the single most important reason why the EITC is so effective at targeting those in need, why it incentivizes work and, perhaps most important for those who care about cities and metros, why it is able to target ever-changing geographies of poverty.

Cities and metros concerned about poverty – and the adverse education and health outcomes that perpetuate it — should be particularly upset that one side of the presidential campaign fails to recognize how tax policy results in less poverty and more workers in the United States.