While cities across the U.S. struggle to attract new talent and keep their economies from stagnating, many young people fresh out of college find themselves struggling to pay their loans. Now, some believe there’s a way to help fix both problems at the same time.

With this goal in mind, the New jersey Assembly last month introduced a bill that would provide economic inventives to recent college graduates to move to certain parts of Camden, Trenton and Jersey City. If passed, the Urban Scholar Revitalization Initiative would offer up to $7,000 in reimbursement for tuition fees.

Sponsored by members of the Assembly representing the three cities, the pilot program would be administered with New Jersey’s already existing Urban Enterprise Zone Authority, allowing businesses that receive tax credits under the program to earn further credits for helping recruit more young people to the program.

New Jersey wouldn’t be the first to consider or even pass such a bill. Niagara Falls, N.Y. is known not only for its spectacular views, but also for a dying population. A city that once had more than 100,000 residents is petering dangerously close to 50,000 — any lower, and the city would lose the requirements needed for many state and federal programs. The city has channeled $200,000 for its own incentive program.

Camden, N.J. has seen massive population loss and disinvestment. Credit: Danny Howard on Flickr

Joining Niagara Falls is the state of Kansas, with 50 participating counties (called Rural Opportunity Zones rather than municipalities) offering incentives. Kansas is acting aggressively: Via waiving income tax for five years and offering up to $15,000 in loan reimbursements, by October 160 people will already have received payments as new residents of the state. Nebraska is now considering a similar program; a bill is on the 2012 legislative agenda.

Detroit, famous for its massive population hemorrhaging, is playing host to the Hudson Webber Foundations’ “15 by 15” initiative, aiming to have 15,000 young people working in Detroit proper by 2015. Through its “Live Downtown” program, employees of companies like Quicken Loans can receive subsidies for housing and mortgages.

So, what is the logic behind these new incentives? We recently discussed Richard Florida’s contested Creative Capital theory, along with Ed Glaeser’s Human Capital theory. For Florida, a city must invest in amenities and Bohemianism to attract talent. But for Glaeser, what cities should invest is in people. It seems this approach is a go-for-the-jugular attempt to get what cities desperately need: talented people who make money. With new talent, cities would be able to expand economically, attract new businesses, increase tax bases and revenue, and stem population loss, creating a viable, vibrant urban environment.

The question now is will it actually work? What will make or break these programs is readily accessible work for these young graduates. Even if a city offers money to help cover student debt, if a lack of nearby jobs means that graduates wouldn’t be able to pay off the rest of their debt, let alone afford an apartment. For Niagara Falls, proponents of their new law point to nearby Buffalo as a source of employment. But Buffalo too is in need of help. And rural Kansas and Nebraska aren’t exactly booming (though they aren’t totally crippled, either). Though, it might be an important way to stem brain drain. In Kansas, a majority of those qualified for the program had ties in the region.

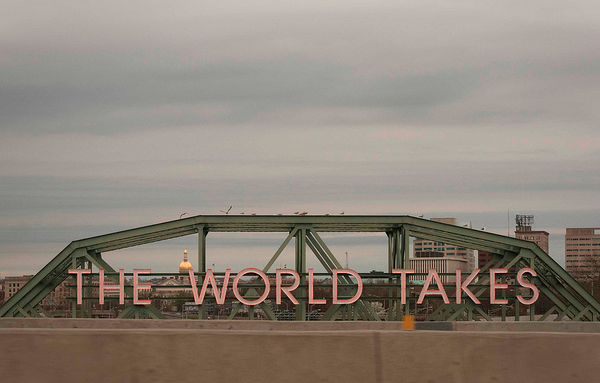

Jersey City has already seen a great deal of reinvestment. Credit: Willem van Bergen on Flickr

What makes the New Jersey program interesting is the state’s ideal geography: Major employment centers like Philadelphia and New York City are only a short train ride away. Camden has the PATCO high-speed rail line Center City Philadelphia in nine minutes. Jersey City has the PATH subway system directly to lower and midtown Manhattan. And Trenton has the SEPTA R7 to Suburban Station in Philadelphia in an hour, and the New Jersey Transit Northeast Corridor service to New York’s Penn Station in roughly an hour and a half.

But is this all too perfect? If the program fails, it would be yet another example of wasted money that could have gone to services such as police and education. But if it works, it could help bring much-needed investment and serve as a future model for other struggling cities.

As of yet there are many details that need ironing out. How will students find out about these programs? How will they be advertised? How much money will be allocated? After all, success hinges on whether graduates will actually heed the call.