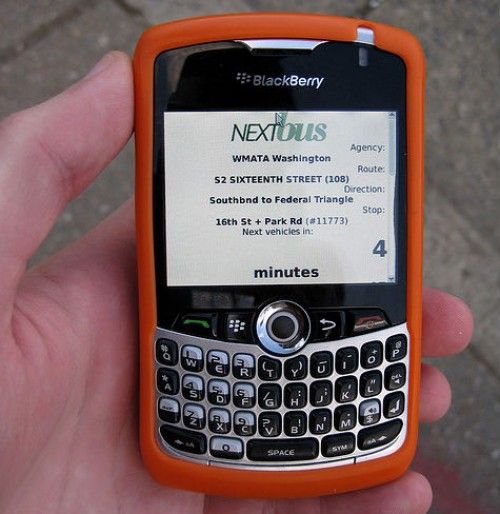

Commuters in Washington are still bemoaning the fall of the popular predictor app NextBus DC, caught up in complexities over data access rights. But NextBus creator Ken Schmier is looking ahead.

“Frankly,” says the Bay Area attorney and businessman, “I think transit agencies are obsolete.”

Schmier’s eyes are on what he’s calling Micro-Transit. The goal: To turn every car in America into a taxicab.

His vision, detailed in a white paper shared with Next City, is to put radio-frequency identification chips into the hands of passengers — in key fobs, transit cards or even driver’s licenses. Willing drivers, in turn, would be equipped with readers. When a potential passenger comes within scanning distance of a participating car, the driver’s picture would appear on an external display, and the rider’s on an internal one, confirming that both have gone through a background check.

Making the moment ripe for Micro-Transit, concludes Schmier, is that the technology is newly affordable: About $2 for the chip and $200 for the reader.

As for passengers getting where they need to go, drivers might opt for a signal showing the direction the car is heading. Longer trips could require hops between cars.

The program is good for cities, says Schmier. Tapping private cars’ “excess capacity,” i.e. empty seats, cuts down on underused public transportation, creates feeder lines to high-traffic trains and buses, and saves gas.

As for providing incentive enough to make drivers willing to let a stranger in their car, Schmier envisions a small fee — 50 cents or a dollar — that would be deposited in their Micro-Transit account for each rider picked up. Or, drivers might opt for high-occupancy vehicle credit. With that, “it behooves everybody to participate, even rich people,” says Schmier, “because they want access to that HOV lane.”

If citywide car sharing sounds crazy, Schmier has four decades of experience moving fringe transportation ideas to the mainstream. As a student at Hastings College of the Law, Schmier noticed that he’d ride the Muni train to school each day but save the fare and drive in at night, when parking was abundant. So, he proposed a limitless Muni Fast Pass, which San Francisco adopted in 1974. NextBus first got attention during the “Muni Meltdown” of the summer of 1998, but didn’t go system-wide until 2001. It has since spread to Oakland, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Boston, Toronto and beyond.

With Micro-Transit, Schmier is eager to discuss all possible concerns. He’s floated the idea of a “Bohemian Club for Street People” to meet the needs of those who might otherwise use public transportation as a place to stay warm and dry.

Schmier predicts his tool would actually serve less dense areas better than public transit. “There are people basically going where people need to get to,” he says.

There’s precedent there. Go Geronimo, a now-defunct program founded in 1996 in Marin County’s semi-rural San Geronimo Valley, paired passengers and drivers on the way along the area’s one real road, Sir Francis Drake Boulevard. Registered participants signaled one another by flashing laminated IDs.

If need be, says Schmier, drivers’ fees in underserved areas could be calibrated upward.

Registered car sharing is something of a formalization of the casual ride sharing known as “slugging” that’s popular in the D.C. area. Schmier points to Avego, an app-driven ride sharing network, as an effort in the similar spirit. Adopting Micro-Transit into a municipal program might help it avoid some of the problems with taxi authorities encountered by the private car service Uber.

Micro-Transit’s program costs, he says, could be paid for with a car tax in the $100 range. It’d be politically palatable, he argues. Drivers would either expect to use the program themselves or it would clear other drivers off the road. Says Schmier, “I could equip every car for one-tenth the cost of Muni.”

For those Washingtonians still focused on when they’ll get their favorite bus predictor app back, Schmier has good news. A new version, called iCommute DC, is in beta testing.

Nancy Scola is a Washington, DC-based journalist whose work tends to focus on the intersections of technology, politics, and public policy. Shortly after returning from Havana she started as a tech reporter at POLITICO.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)