Last week the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland released a study finding that poverty is on the rise across the nation. Midwest urban areas have seen particularly intense spikes, while Northern cities have the heaviest concentrations of urban poor.

As the report notes:

[T]his increase was most rapid in neighborhoods that already had a large share of poor residents. This increase in the concentration of poverty is a distinct cause for concern because the disadvantages to an individual from being poor are thought to be either muted or amplified depending on the poverty in their neighborhood. Neighborhoods with many poor residents typically have less access to job opportunities, face higher crime rates, and incur a range of other social problems.

New Jersey is home to many such urban areas: Camden, Atlantic City, Trenton, Newark. But it is also one of the few states with a policy toolkit that could theoretically help break up clusters of poverty by integrating affordable housing into prosperous suburban areas, allowing low-income people to live in wealthier neighborhoods and school districts with greater resources.

Due to a series of court decisions, broadly known as the Mount Laurel Doctrine, the state prohibits municipalities from instituting housing exclusionary policies and requires that they zone for a “fair share” of the region’s affordable housing. “Affordable” is defined as housing costs that equal less than 30 percent of household income.

The first case was opened in the late 1960s by low-income African-American residents of Mount Laurel Township, 15 miles to the east of Camden. The town was growing increasingly expensive and zoning codes precluded multiple-unit rental housing, which is cheaper (and more environmentally-sound). Like other municipalities, Mount Laurel was trying to use zoning policies to maximize its tax base and push out low-income residents by encouraging the construction of larger houses for richer people, not to mention shopping malls and office parks. One town councilman is reported to have said, “If you can’t afford to live in Mount Laurel, pack up and move to Camden!”

In 1975 the New Jersey Supreme Court decided in the plaintiffs’ favor, but the township continued to defend its segregationist policies. It took a 1983 court ruling from the New Jersey Supreme Court to firmly establish the Mount Laurel Doctrine.

It is hard to argue that the decision has been particularly onerous for New Jersey cities and towns. Only 60,000 units of affordable housing have been constructed since the 1980s as a result of the doctrine, not even close to meeting demand (46.7 percent of New Jersey homeowners and 54.3 percent of renters are cost-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing). Mount Laurel Township itself managed to put off opening its own affordable housing development, the Ethel R. Lawrence Homes, until 2000 after most of the original plaintiffs died. Last year the Star-Ledger ran a story on people who managed to leave Camden by way of the Ethel Lawrence Homes.

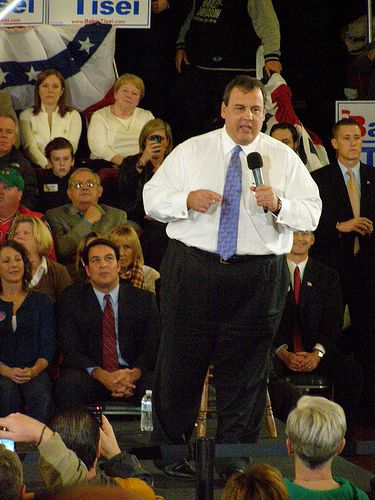

But according to New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, the Mount Laurel Doctrine is “an abomination.” He campaigned against it in the 2009 election, in a bid to secure the votes of higher-income suburban residents, and has persistently tried to undermine the law since being elected. In 2011, he tried to eliminate the Council on Affordable Housing (COAH), which administers the doctrine, declaring, “This is about getting Trenton the hell out of the business of telling people how many units they’re supposed to have… We need to lift that wet blanket off of the municipalities.”

Chris Christie campaigned against Mount Laurel Doctrine. Credit: Marissa Babin on Flickr

Christie’s attacks are of a piece with upper-income New Jersey’s history of massive resistance to the Mount Laurel Doctrine — hence the small number of affordable housing units actually constructed. The law comes under attack so frequently that there is a firm, the Fair Share Housing Center, devoted almost entirely to defending it.

Last week the New York Times ran an unsigned editorial decrying the two cases currently pending against the Mount Laurel Doctrine. The first regards a 2011 attempt to effectively reorganize COAH’s out of existence by executive order, which was quickly enjoined by an appellate court, and has since been wending its way through the judicial process.

The other case is Christie’s attempt to reformulate the way that municipalities’ affordable housing obligations are calculated. Under this plan they would be allowed to revert to their old ways, expanding their tax base with sprawling suburban business developments at the expense of lower-income residents. Business development would require no affordable housing development at all.

“It would leave the 565 mayors of New Jersey in a fight over which town can draw the most tax base,” said Kevin D. Walsh, associate director for the Fair Share Housing Center. “This would leave the towns that don’t grow the tax base to house the lower income workers working in the malls that the other municipalities are building. What he is advocating is a recipe for sprawl and inequity in land use. This would return home rule to municipalities over decisions that have widespread regional consequences.”

Walsh said that it’s unlikely Christie will triumph in the courts, although while the judicial process grinds on, the embattled COAH is in stasis and new affordable housing units construction has slowed considerably. But multiple studies have found that the actual effectiveness of the Mount Laurel Doctrine, when it is allowed to operate unencumbered, does not seem to be in doubt.

A comparative study for the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy analyzed the effect of smart growth policies on affordable housing stock. Over the course of the 1990s, in three of four states with smart growth policies — Maryland, Oregon and Florida — the proportion of households paying more than 30 percent of their income for housing increased. (These states also tended to have higher average incomes and market demand than the control states used in the study.) The exception among the smart growth states was New Jersey:

Its statewide housing program, the progeny of several state supreme court [sic] decisions, clearly propelled the production of affordable housing, including the expansion of rental units… While New Jersey’s housing costs were high, its renter cost burden increased less during the 1990s than in the other smart growth states.

The state Supreme Court decisions are, of course, the Mount Laurel Doctrine.

A 2009-2010 study of the Ethel Lawrence Homes, by Princeton University Professor Douglas Massey, showed “no detectable effects of the project’s opening on any outcome… Trends in home values, crime rates and taxes were the same in Mount Laurel as in similar townships nearby.”

But the real story is the effect the affordable housing development had on its residents. By comparing those who applied but hadn’t secured a housing unit to those who did, the study found the first group suffered significantly less violence and what are delicately termed “negative life events.” Employment rates were higher for those who lived in the Ethel Lawrence homes, as were incomes. Their children enjoyed “significant indirect effects through hours studied, school quality and school disorder, which on net improved grades.”

The Mount Laurel Doctrine is meant to de-concentrate low-income populations and allow them access to the social goods afforded by wealthier communities. If anything, it has not been allowed to reach its full potential. Combating segregation and inequality benefits the whole state, and would benefit the whole nation if emulated widely, by increasing incomes, tax revenue, safety and access to good education. Combating affordable housing opportunities does none of those things.