A colleague of mine —who coincidentally was also one of my favorite transportation policy professors— has an especially esoteric collection of office memorabilia. Seeing the odd model train or toy subway car wasn’t out of the ordinary in an office dedicated solely to transportation planning and consulting. But this colleague, let’s call him Jason, has plastered most of his space with endless statistic myopia. It looks like the office of a mad scientist, obsessed with finding a solution to an impossible problem or creating a perfectly efficient, Frankenstein of a car—a KITT with a taste for biodiesel.

When I looked a little closer and took the time to read the titles of all Jason’s charts and graphs things become a little clearer. Most of the information stuck to the wall with prismatic pushpins actually has to do with how American’s spend their money, especially when it comes to transportation. It was obvious that Jason wasn’t the only one interested in that trend; every graph, chart, and paper had a different scribe.

It costs a lot to go places. T.R. Lakshmannan once converged the theoretical and practical definitions of the mercurial subject: “transportation is providing the utility of a faraway place.” That’s the entire package: when you drive somewhere, the destination is simply providing you a benefit for a cost and the cost is the travel. It may hurt to think about but you never get to your job for free because you’re either going to pay for gas, pay for a subway ticket, pay for a bike, or pay for a new pair of shoes. In a basic sense, improving transportation is really about reducing that cost for all parties—though driving down the price of a good pair of loafers may be beyond that scope.

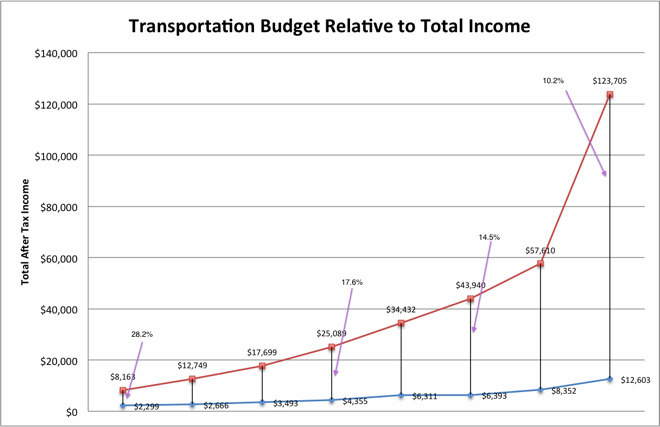

One chart in Jason’s office is conspicuously centralized among an ocean of otherwise scattershot pieces of paper. It shows the spending habits of Americans distributed by their income brackets. Scaled isosceles triangles exhibit how much we spend on clothes, food, and education as a function of total income. And there, in bold, is transportation. The data is gleaned from the Consumer Expenditure Survey managed by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (the most recent dataset is from 2009) which breaks behavior down into earnings brackets up to $70,000 a year—American families who make more than that are clumped together, a dismissal that speaks to the purpose of a survey like this. The dataset is invaluable to breaking down the trends of the modern American consumer as well as identifying potential areas of ghastly disequilibrium.

There are sure to be sectors of the economy where poor Americans spend a terrifyingly disproportionate amount of their income, but transportation is one that has recently caught the eye of planners and journalists alike. A gas tax increase, a concept as boring as it is indispensable, has been in the limelight locally and nationally and is, depending on whom you talk to, economically disastrous or politically unpalatable. Another concept that has gained traction in the Pacific Northwest is based on how far you drive rather than how much gas you buy. But charging for Vehicle Miles Traveled or VMT ignites an all-American brand of paranoia and conjures up images of tiny tracking devices recording your every word and perhaps even that time you got ice cream instead of going to the gym.

The issue, of course, isn’t nominal, it’s proportional. Poor Americans are spending a much higher percentage of their income on a good that should have been engineered into near-obsolescence. The problem of family transportation budgets outside of the cost of gas receives surprisingly little attention in policy circles and news outlets because it lacks the melancholy glamour and tragedy of food prices and foreclosures. But going back and forth from work, school, and leisure can damage a family’s budget as much as any other commodity crisis. There will never be a free way to get somewhere; travel, like thermodynamics, will never hit perfect efficiency. There is room for improvement, however. If there are people making $17,000 and spending 20 cents of every dollar on transportation then maybe it’s time we started reinventing the wheel.