Jeff Speck’s newest book, Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time, aims to show how making downtowns into places where people want to walk will both spur economic development, restore the environment and fuel broader adoption of the urban lifestyle. Speck’s slim, highly readable volume supports these ideas with studies and firsthand observations from the frontlines of redesigning urban America. Overall, it’s a quick book filled with micro and macro evidence that both challenges traditional urban thinking and is tough to argue with.

The first third of Walkable City is a simple argument for focusing on walkability. A tip to the busy reader: If you already believe that walkability is the key to improving urban life, then just read the succinct prologue then skip all the way to page 71. You might miss some great factoids, but otherwise it’s going to be 50 pages of preaching to the choir.

On the last page of the first section, though, Speck introduces his “General Theory of Walkability,” consisting of 10 elements communities must embrace to get there. You won’t find a summary of those steps below. For that, you need to read the book (and tell us what you thought about it in the comment section below). Instead, let’s focus on six of Speck’s statements that urbanists and civic leaders are likely to question — even those who tend to agree that walkability should be a priority.

I. Specialists give bad advice, pg. 81

There are probably half a dozen stories throughout each book of cases where cities overinvested in the wrong assets (traffic lights, sidewalk expansions, etc.) because the specialist who advised them to do so also stood to make a profit. It boggles my mind that communities commission studies from the same firms that will ultimately do work on a given project, but it happens a lot.

I used to work as an environmental advocate, urging township leaders to modify local code in many of the ways Speck suggests (though for different reasons). Again and again, I saw elected officials (generalists) defer to their engineers (specialists), despite the fact that the latter’s interests were with their firms and the former’s with their town.

Speck takes this point one step further with a thought experiment asking, what if every single kind of urban advocate got their way on street and sidewalk width? By his calculation, you would have a typical main street some 175 feet wide — a daunting hike for a walker, just to go from the drug store to the bank.

II. Parking meters are good for storefronts, and higher prices make them even better, pg. 129

It was surprising to learn that the parking meter was first deployed in Oklahoma City, a place known for sprawl. Not only that, but when the first parking meters went in on one side of the street, it wasn’t long before business owners on the other side clamored for them.

How can that possibly be when downtown business leaders across the country routinely fight parking hikes for fear that it will drive away business? The reality is simple supply and demand. When the price is right for on-street parking, people use just as much parking as they need. Which a) means customer turnover is higher and b) customers are more likely to drive to a particular block because they feel confident they will find a spot when they get there. The market should play a greater role in setting parking prices. Which brings us to our next point.

III. American parking is socialist, pg. 116-120

Speck points out that American cities nearly universally have off-street parking minimums, usually designed around peak use. Under this system, everyone pays for parking, whether they use it or not. Mass transit users, cyclists and walkers all pay for parking they don’t need when shopping in stores built under minimum parking requirements. It’s pure parking socialism (my word, not Speck’s). We would all be better off if cities let the market decide how much off-street parking they need and build to their expectation.

In my review of Michael Chabon’s Telegraph Avenue, I mentioned the growth a Metro stop brought to D.C.’s Columbia Heights neighborhood. Speck writes about the same place, adding a depressing anecdote about the millions of dollars in waste brought about by minimum off-street parking requirements in a project that has otherwise been a runaway success.

IV. The less safe a street appears, the more safely drivers behave, pg. 172

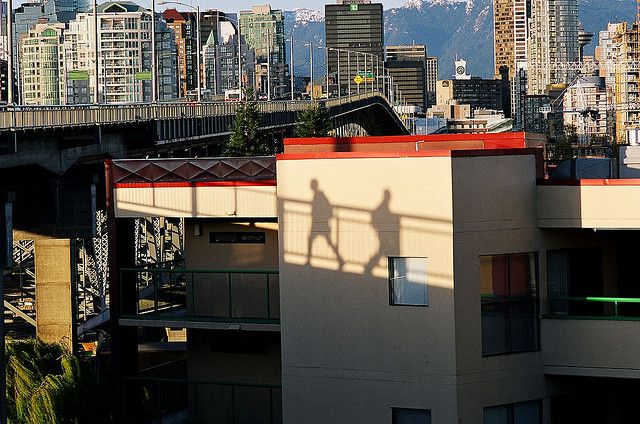

The Philly intersection Speck credits for its chaos. Credit: Charlene Mcbride

Speck didn’t completely sell me on this one, but he argues it well. His point is that drivers are aggressive in places designed for easy driving. As an example he uses a very famous intersection in Philadelphia. If you haven’t been, the two biggest cheesesteak joints in town face each other from across an intersection of two diagonal streets. And other perpendicular streets cut in a little to the north and south. It’s a chaotic place and, in Speck’s observation, very safe for walkers. It is always full of people, and drivers are watching out.

Maybe. Or maybe drivers will get accustomed to it and start behaving badly again, but under more unpredictable conditions. I observed a lot of really scary driving when I was living in North Philadelphia, a place where kids treat streets like playgrounds and every driver there knew it.

This is just the beginning, though. Skip to page 176 for the concepts of “naked streets” and “shared space,” probably the two hardest-to-swallow concepts in the whole book.

V. Mass transit doesn’t decrease driving, pg. 148

Just typing that out made me feel like I was breaking some sort of urbanist taboo. Speck argues in detail, though, that the only way you decrease the number of drivers is by making driving more expensive (in cost or convenience). He points to the case of the Dallas Area Rapid Transit, where billions have been spent connecting by rail the suburbs to Dallas’s center. There are just as many drivers now as there was before, because even the very underwhelming ridership attracted by DART has only freed up the roads for other drivers. Furthermore, DART connects spaces designed for drivers to spaces designed for drivers. So why not just drive the entire way? (And maybe take a cue from The Onion‘s strategy for dealing with traffic?)

VI. Trolleys don’t bring pedestrians — pedestrians bring trolleys (and Zipcars), pg. 151

Speck points to small cities that hope to stimulate a walkable environment by building streetcars and trolleys of different kinds. Streetcars, he said, work well when you already have pedestrians. They work as pedestrian accelerators, helping people to cover more ground on foot. But if the people aren’t already there on foot, your streetcar probably won’t do much good. In much the same way, he points out that Zipcar likes to invest in cities where a person can mostly give up car use. Zipcar covers the mostly. But if you’ve got a town where just picking up the dry cleaning is a chore without a car, it probably isn’t ready for car sharing.

Speck makes other observations that might strike an urbanist reader as counterintuitive. As a teaser, I will just say that his Step 10, “Pick Your Winners,” may be his most challenging notion of all. I won’t explain it here, but it’s a good one.

This book reads quickly. It is loaded with illustrative stories and humor. I have a whole page filled with sources to follow up on after reading. Maybe you will have the same experience reading Walkable City and, if you do, please let us know. There is a lot more in here to talk about.

Brady Dale is a writer and performer, living in Philadelphia. Find him on Twitter.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)