“This complex is under constant video surveillance,” declares a bright orange sign on the façade of the otherwise cheery Euphoria Café. A list of regulations follows: No drinking, no biking, clean up after your dog.

At the bottom of the sign, in small typeface: “This is private property.”

It was here within the Piazza at Schmidt’s — a gleaming, glass-and-red-brick mixed-use retail, commercial and residential development in Philadelphia’s Northern Liberties neighborhood — where on the night of June 11 a fight between two men ended with one of them, 24-year-old Maurice Gimble, dead. His suspected shooter, Steven Miller, 22, was apprehended Wednesday morning in Houston, Texas, having been on the lam since the incident.

Gimble’s killing was the third in the Piazza since it opened for business in 2009 amid controversy over changes that the $30 million complex would bring to Northern Liberties, then a quiet, gradually gentrifying outpost of working-class families and artists. The murder has ignited discussion over how public security fits into an increasingly common breed of urban space: The privately owned and occupied public plaza.

—

Zuccotti Park on the evening of Nov. 15, 2011, just after a police raid cleared occupiers. Credit: ChristiNYCa on Flickr

As cities look to revitalize their downtowns in an era of dwindling municipal resources, more and more are turning to developers to draw investment back into their downtowns through privately operated and managed public spaces.

New York City’s Bryant Park is perhaps the best-known example of this sort of space. Spanning four city blocks in midtown Manhattan, the park is host to thriving businesses, restaurants and thousands of visitors lounging in the open green space. In the 1960s and ‘70s, the park, at that time administered by the city government, was a favorite stomping ground for drug dealers and sex workers. The hedges surrounding the central plaza, festooned with garbage and obscuring a view of the park from the street, provided cover for New York’s illicit economy. With improving public safety in mind, plans were developed during the ‘80s to turn the park into a business- and pedestrian-oriented public space.

Reopened in 1992, the park, though still technically public, is now privately managed by the Bryant Park Corporation. The area sees in excess of 4,000 lunchtime visitors a day and is one of the safest areas of New York, according to the Project for Public Spaces, who indicate that there has only been one robbery in the park since 1981. Jerome Barth, the corporation’s vice president of business affairs, said the key to turning around the space was keeping eyes on the street.

“Number one is the public,” said Barth. “The law-abiding citizens who use the park are the ones who keep it safe.”

A similar strategy is at work in downtown Las Vegas where developer and Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh has attempted to spur investment, in part through bringing people and activity to privately owned open spaces.

Another, more striking example is Zuccotti Park, the privately owned public square of Occupy Wall Street fame. During the seven-week encampment, reports of often-brutal crimes began to surface almost as soon as the first tents went up. Criminal activity became so common and was so underreported that New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg took the unprecedented step of asking protesters living in the tent city to patrol themselves. And once the city had had enough, the police raided the encampment on the morning of Nov. 15, emboldened by the park’s status as a private space.

Design elements of these spaces may have the potential to influence public safety outcomes within them, said Harris Steinberg, an assistant professor of design at the University of Pennsylvania and executive director of PennPraxis.

“There might be some truth to the idea that the design quality of Bryant Park permits a kind of urban watchfulness,” explained Steinberg.

While the shops and apartments ring and enclose the Piazza, every part of Bryant Park is visible from any of the adjacent streets, businesses and homes, a result of clearing and leveling in the late ‘80s. That said, there remains a difference between public space under private management and privately owned public space, a difference that can determine where responsibility lies in ensuring safety.

Though eyes on the street have tamped down crime and violence, Barth admitted that the Bryant Park Corporation’s security contractor does collaborate with city police, but insisted that turning to police is a last resort.

—

Northern Liberties, an old part of the city whose economy was hobbled by Philly’s transition away from industry and manufacturing, is slowly turning around after decades-long disinvestment. Just north of historic Old City, the neighborhood can barely resist comparisons to token examples of gentrification in other large U.S. cities.

A smaller, twitchier version of New York’s Williamsburg, a buttoned-up cousin of New Orlean’s Marigny, NoLibs — half pejorative, half pet name — has seen slow but steady development, moving in inches down 2nd Street. Gastropubs and quirky boutiques are lighting up retail properties left vacant after the collapse of the breweries, tanneries and metal works that buoyed the local economy for most of the 20th century. Though still solidly working class, the recent influx of young people and white-collar professionals has given a neighborhood a facelift.

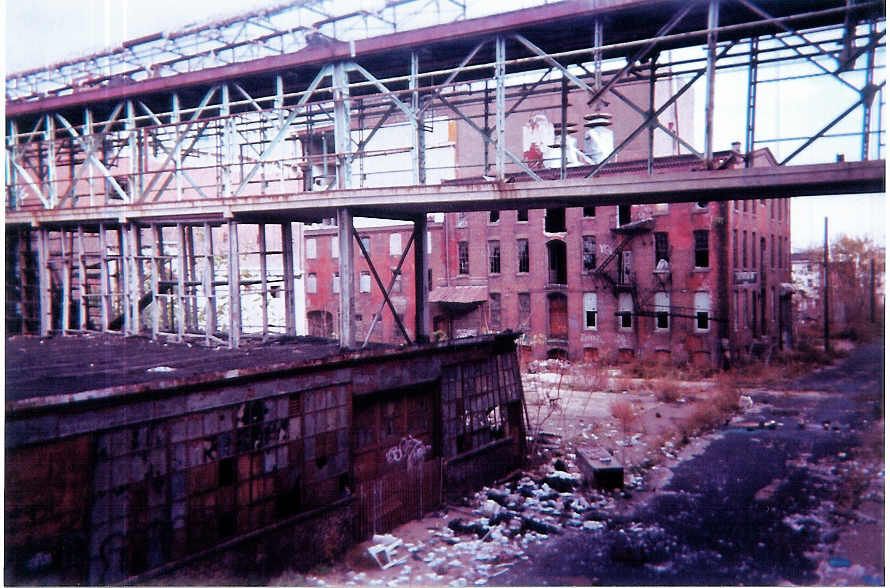

Enter Bart Blatstein. A Philly-based real estate development potentate, Blatstein and his development arm Tower Investments, Inc. bought the old Schmidt’s Brewery in 2000 for $1.8 million at a sheriff’s auction. The property sat on 8.5 acres at the northern end of Northern Liberties. They reopened the site as The Piazza at Schmidt’s, leaving just one of the warehouse’s walls in place, still adorned with Schmidt’s stylized logo.

Schmidt’s Brewery before the site was redeveloped. Credit: jponte12533 on Flickr

“Whatever was going on in Northern Liberties, Blatstein accelerated it,” explained Steinberg, the Penn professor. Hesitant to call it gentrification, Steinberg notes that Blatstein’s arrival capitalized on an already burgeoning arts scene and an inflating demographic of those willing to pay for the new amenities the Piazza would bring. “He was really targeting those 20- and 30-somethings with disposable income.”

Completed in 2009, the Piazza at Schmidt’s — a name referring to the development’s design homage to ancient Roman public forums — became the elephant in the backyard of the neighborhood: A 500-unit residential complex, retail space and restaurant storefronts surround an 80,000-square-foot plaza. It is a private development designed for unrestricted public use, with most of Blatstein’s subsequent development projects in the area radiating out from it.

The jury has since been out on whether Northern Liberties, with all its vital energy and enduring history, now culminates at the Piazza. “The Piazza is certainly a public place, but whether a person feels it is the center of the neighborhood depends on how long they’ve lived there,” said Matt Ruben, president of the Northern Liberties Neighbors Association.

Ruben, a 12-year resident of the area (he closed on his home the same month Blatstein closed on the brewery site), suggested that Blatstein’s project has, to a degree, been successful in appealing to the intended crowd. “The Piazza has raised Northern Liberties’ profile as a destination,” he said.

Still, it remains unclear if the Piazza has been fully enmeshed in Northern Liberties’ social fabric. “The neighborhood looks very different to visitors or to residents,” said Ruben.

Now that the safety of the Piazza has been called into question, some neighbors have expressed concern about security presence.

“A lot of the feedback we’ve gotten from neighbors has been about some kind of enhanced security,” explained Ruben. In a small group meeting last week, Ruben indicated that a discussion was held between neighbors and police in order to help ease fears about. “The police reminded us that Northern Liberties was still one of the safest areas in Philadelphia.”

Police Capt. Mike Cram, of the 26th District that covers Northern Liberties, said that police assured residents of the neighborhood’s safety at the meeting. Though unauthorized to give statistics when reached for interview, he was adamant that the murder in the Piazza was simply a freak occurrence in a neighborhood without much endemic crime.”

We said we’d tighten things up,” he said, “but really there isn’t much going on over there.” Not much is going on over there, at all.

—

Even after police calmed tensions in Northern Liberties, some of the development’s tenants are looking to jump ship. On June 13, Molly Auer made headlines when she posted to Tower Investments’ Facebook wall that she and her boyfriend wanted out of their lease.

“Last night I awoke to gun fire and witnessed a man dying on a gurney to an ambulance,” wrote Auer. “I would now like to move. We have kindly asked to get out of our lease, so now I will be posting here everyday until you oblige.” According to Curbed Philly, Tower Investments hastily deleted the post and blocked Twitter users from retweeting it.

The total number of tenants looking to withdraw from their rental obligations, or whether Tower Investments intends to ramp up its private security detail, is unknown; no tenants have responded to requests for comment.