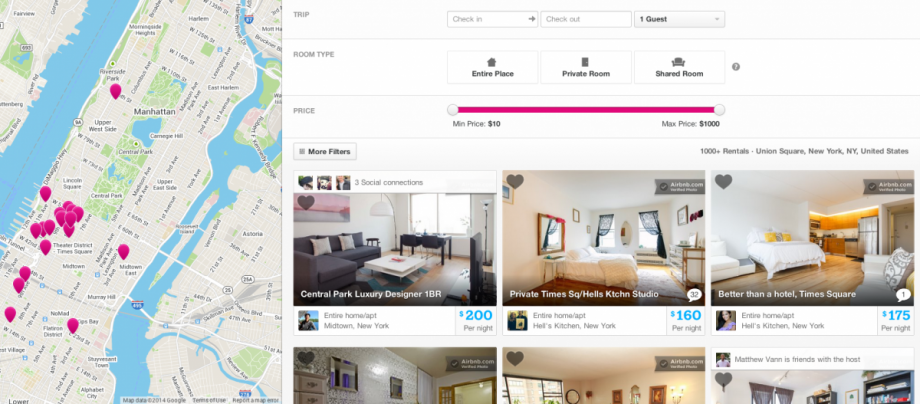

New York State Senator Liz Krueger (Dem.) represents five hundred blocks of the world’s choicest real estate— a district that stretches from just below Union Square all the way north to 96th Street. Around the time she was first elected to her senate seat in 2002, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia were meeting, a three-hour straight-shot up Interstate 95, as undergraduates at the Rhode Island School of Design. It would be years before the two would go on to launch the housing-rental website Airbnb.

After taking office, Senator Krueger began hearing complaints of tourists and transients traipsing through her district’s residential buildings. She dug in. By 2007, she was condemning landlords for “pushing moderate and low income people out of those units and suckering tourists into renting illegal rooms.” Meanwhile, within a year, the brand-new airbedandbreakfast.com was garnering great press as a clever matchmaker for housing at Denver’s overbooked Democratic convention, and not just, reported Crain’s Chicago Business, “for the futon crowd.”

In 2010, Krueger successfully championed the Illegal Hotel Law, state legislation that streamlined and strengthened enforcement against sub-30-day residential rentals in New York City. As the bill went into effect, Airbnb was completing its first big funding round, worth more than $100 million. In recent months Senator Krueger and Airbnb have been at odds. The state’s attorney general has been targeting “hosts” who illegally rent out whole apartments, but it is Krueger who has positioned herself as Airbnb’s leading skeptic in high-stakes New York. She has accused the company of inducing an unknowing public into breaking the law, last week slamming the company for blithely facilitating “floating brothels.”

“Throughout the history of the world” says the senator, “there have been people who have said, ‘I’m going to go visit the grandchildren for the week. Wouldn’t it be great if I could make a little money on my apartment while I’m gone?’ But the Internet and the ability to exchange information and money with strangers has blown it up beyond comprehension.” In our interview, we discussed Airbnb’s legal status New York City, turning down tens of millions of dollars in hotel tax, and what the problem is with leaving keys at the bodega.

Next City: What do you say to a constituent who says, “Why would you begrudge me renting out my place for the weekend to make a little extra money? What’s so wrong with that?”

Liz Krueger: If you live in my district, I would say, “Do you live in a private home?” And they would say, no, because people who live in private homes in Manhattan are statistically multi-millionaires who don’t need to rent their places out. But I would say, “Do you live in a private home? And in which case, there’s no issue. Make your own decisions.”

But if you live in an apartment building with people living to the right and the left, below and above, your right to let strangers stay in your home for money impacts all your neighbors. Did they sign off on the deal?

It’s also very unlikely that it’s legal under your lease and co-op or condo bylaws. I would say, “I hope you know that you can be evicted from your home, even if you own it. Are are you prepared to take that risk?”

NC: But the legal basis for opposition seems to be your Illegal Hotel Law…

Krueger: You know, they say that. But not so much. The 2010 law means that there are tools for enforcement for complaints that have gotten to the level of government. The underlying question of, “Is it legal?” where the answer is no — that’s been true long before the law I passed. That law gives tools to particularly go after people who are renting apartments to turn them into illegal hotel units on a full-time basis, who rent two, three, nine, 25, a hundred and ten apartments, and literally turn them into 365-day-a-year sites.

But, “I’m going away for the weekend, why can’t I rent out my apartment?” It’s not my law that’s really the issue for them.

NC: San Francisco is considering a law to allow sub-30 day residential rentals with licensing and registration. Would you be on board with that?

Krueger: When you look at the volume on the Airbnb site, a huge percentage are not the going-away-for-the-weekend. They are the, “I rent out apartments to take them off the residential market and put them into illegal hoteling.” That’s the biggest problem.

NC: But would you support something like the San Francisco law?

Krueger: Probably not, because in discussions with city governments they discuss how impossible enforcement would be. It’s not just registering. It’s also confirming that person got permission to do so under their lease. In New York City, California, any place you want to name in the U.S., just doing a law like that has very little to do with the legality of whether you can do this in the apartment you live in. I can’t find any place in the county where leases say that you’re allowed to sublet on a daily basis to anyone you want.

NC: Why not then let that be handled at the building level?

Krueger: In New York, if you decide to do that probably nothing happens under existing law. Our law is complaint driven. If the owner of the building says it’s fine and all the tenants say it’s fine, you might still be breaking other laws, but probably nothing’s ever going to happen to you. It’s not an enforcement model where people are running around to every building going “Gotcha.”

My motivation around this topic started with constituents contacting us saying, I’m being harassed out of my own building. Even in that New York Post prostitution story, quote the prostitute: ‘We like this because we use buildings that don’t have doormen or cameras.’ [The quote: “Hotels have doormen and cameras. They ask questions. Apartments are usually buzz-in.”]

I didn’t ever hear about brothels before that New York Post story. But when I was starting to work on this issue seven years ago, I was hearing was from residents saying, “Scary things are going on with total strangers in the apartment next door. People I don’t know have keys to the front door. People are buzzing people in in the middle of the night. Nobody knows them. People are drunk in my elevator. I can’t let people walk around the hallways anymore. People with luggage come in at all hours of the day and night. This is a residential building. What the hell is going on?”

And then we hear from landlords who say, “Crap, what is going on in my own building?” When the city does an enforcement violation, they’re the one who gets hit with a ticket. A common strategy is the person doing the illegal hoteling pays the bodega on the corner a couple bucks to give keys out. The guest is told, “Go to the bodega and ask for the keys to Apartment 14.” When the landlord learns that’s happening, he’s got to replace the front door lock and give every single tenant new keys. Landlords tell us it costs them a thousand dollars every time they get a complaint.

The cover of the New York Post last Monday, April 14.

NC: Does that suggest that the law needs to be even stronger then?

Krueger: I believe the law does need to be stronger. I’m getting constant complaints and companies like Airbnb seem as a business model to want to encourage people to break the law. The problem hasn’t gone away.

And look, it’s New York City. There are certain landlords who would love to empty out their buildings of lower-rent tenants. Before I became a senator I was running eviction prevention programs to help people to stay in their homes. So when I see people say, “I need a little extra money, I’ll just go online and list my apartment on Airbnb,” and then they call up and say, “I’m being evicted,” it sets me off.

Yes, they make have broken the law. But I’m indignant that Airbnb and other companies say, “We have no obligation to tell people that they’re breaking the law and are at risk of losing their homes over it.”

We’ve had multiple discussions directly with the company. We know they’ve had multiple conversations with the state attorney general. Everyone has said, “Put the information up on your website.” Let people know at X location that if they participate, they could be at risk of violating the following laws and losing their homes. And put up information for guests saying, “If you have a terrible experience there’s very little you can do about it.” If you did that, a whole lot of people would think twice about putting themselves at risk as tenants or choosing to use this model for their vacations.

But these companies who do the websites keep telling me they have no legal obligation on any of this. They actually say things like, “Well, we’re doing this all over the country. There are different laws everywhere. How could we possibly keep track?” Wherein we respond, “You’re in the Internet business. You’re very skilled at computer websites.”

I mean, I can’t even talk the tech language you and Andrew [Goldston, Krueger’s communications director] talk. But even I could figure out how to do a pop-up that says, “If you’re planning on renting out in New York City, here are the rules.”

NC: Airbnb recently pointed out that hotel industry has complained that it wasn’t paying those taxes, but when they offered to pay about $21 million a year to the city and state, those same people said that the money wasn’t welcome.

Krueger: Not to pooh-pooh $21 million, because you and I both would think that’s a lot of money, but when you take an affordable apartment off the market in New York City it costs the city to replace that unit, at minimum, $500,000. So $21 million in hotel occupancy tax is 42 affordable units. In New York City we’re talking about the loss of thousands of residential housing units. We’re talking about the fact that every time a residential unit is lost it ups the rental cost of other units. So $21 million for all that lost affordable housing? Yeah, no thank you.

And as the attorney general’s office has put it to me, collecting and paying a tax does not make what you’re doing legal. If someone wants to evict you, paying a hotel occupancy tax is prima facie evidence. What’s a judge supposed to do? “Did you pay hotel occupancy tax on your apartment?” Yes, judge, I did. “So I guess you were running a business.”

I suppose someone could go around trying to change contract law so leases cannot say you can’t do short-term subletting without permission. But I’m going to bet you a whole lot of money that’s never happening. People would say, “Are you crazy? We’re not opening up contract law like that.”

NC: What about the idea that Airbnb can be a more affordable, more intimate way of experiencing a city. Hotels can be expensive and…

Krueger: Actually, they vary. They can be really expensive and they also aren’t that expensive all the time. You can find rooms in the $100 to $150 range. Which yes, in a lot of places is still a decent amount of money. But there’s a pretty broad universe. Would I like to see more cheaper options? Yes. We’re working with the city to hopefully create a system where hostels would be allowed to operate. Lots of the world has hostels as a low-cost option. We’re definitely interested in exploring that.

NC: The sense out there is that Airbnb is preparing to go public. Do you feel like you’re standing in the way between them and several billion dollars?

Krueger: (Laughs.) I think that’s their only agenda. I suspect that the current crowd is just desperate to do their IPO. Take their money and run. They don’t really care what the hell’s happening out there.

My law allows some more options for enforcement but it’s minimal compared to the sheer volume of what’s going on. If you don’t have the bodies to do it, that’s not really stopping them.

NC: Have you ever Airbnb’d?

Krueger: I have never Airbnb’d. I’ve been solicited by another company that is going door-to-door, encouraging people to sign up with them to become hosts. Several companies have actually going around fliering to encourage people to do this illegal activity.

I find regularly find myself going online, typing in addresses in my neighborhood, and saying, “Aha.”

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Nancy Scola is a Washington, DC-based journalist whose work tends to focus on the intersections of technology, politics, and public policy. Shortly after returning from Havana she started as a tech reporter at POLITICO.