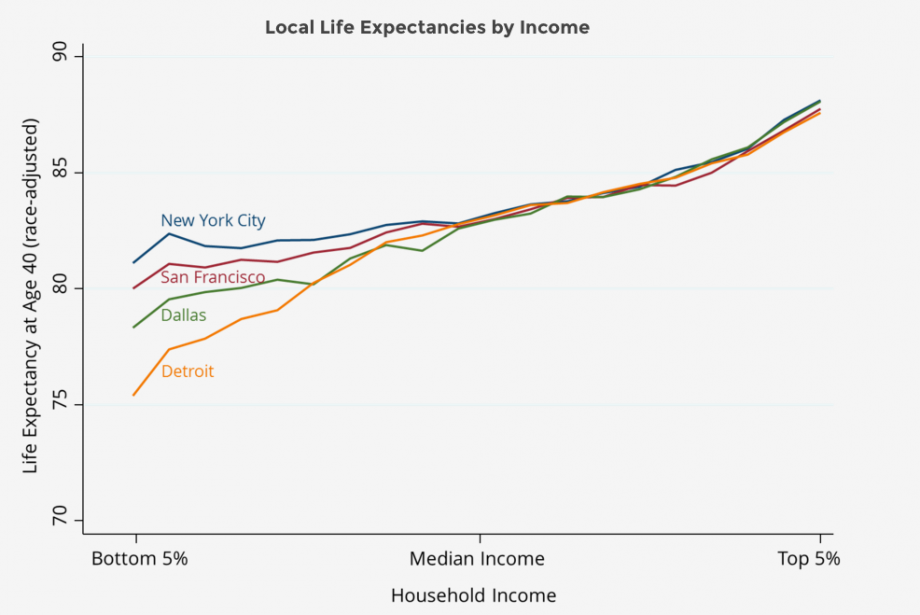

America’s wealthy have gained three years of life expectancy this century, almost without regard to where they live, but for poor Americans, geography can mean the difference between celebrating an 86th birthday and not seeing the age of 76.

According to new research published this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the gap in life spans among the rich and poor widened between 2001 and 2014. The richest 1 percent of American women now live 10 years longer on average than the poorest 1 percent; the richest men live an average 15 years longer. But the pattern didn’t hold everywhere. In some cities, like New York, Miami and Birmingham, Alabama, the poor have seen rising life expectancy this century and live nearly as long as their middle-class neighbors, suggesting that small-scale, local policies to improve public health can lengthen life spans, despite income inequality.

“You want to think about this problem at a more local level than you might have before,” Raj Chetty, the study’s lead author, told the New York Times. “You don’t want to just think about why things are going badly for the poor in America. You want to think specifically about why they’re going poorly in Tulsa and Detroit,” citing two cities with lowest levels of life expectancy for low-income residents.

(Credit: The Health Inequality Project)

The study, the most detailed analysis of the issue to date, suggests many connections between wealth and mortality. There are the obvious reasons: The affluent can afford higher-quality healthcare; they exercise more, smoke less, experience less stress and are less likely to be obese.

But there were many less obvious factors as well. The paper found little correlation between a region’s Medicare spending rate or the proportion of the population with health insurance and the life expectancy of poor residents. It also found that economic factors like the unemployment rate and income inequality had little relationship to life spans. On the other hand, poor residents do live longer in places with higher concentrations of college graduates and high local government spending. A smaller longevity gap was also tied to population density, with wealthy cities topping the list of places the poor live longest. New York City, for example, has the highest life expectancy for men and the second-highest for women. (Miami topped the list for women.) NYC also has a high rate of spending for low-income residents and aggressively regulates unhealthful behaviors like smoking.

Birmingham saw an increase in life expectancy for adults in the bottom quartile rise 3.8 years for men and 2.2 years for women between 2001 and 2014. The Times connects those gains to numerous local measures enacted by the county: the expansion of preventative healthcare like vaccinations and mammograms, a portion of local taxes directed to hospital care for those who can’t pay, a countywide ban on smoking in restaurants and workplaces, and philanthropic campaigns to improve health.

“There is a very strong correlation between income and life span,” Thomas R. Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, told the Times. “But it is not inevitable. There are things we can do to change the life trajectory of people. What improves health in a community? It includes wide access to social, educational and economic opportunity.”

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)