In 30 states, calling 911 to report an overdose can land both you and the person you’re trying to help in jail. As of Tuesday, Pennsylvania is no longer one of them. At least not in principle.

This week, Governor Tom Corbett signed the 911 Good Samaritan law. Under the provisions of the law, citizens who report an overdose in good faith are granted limited immunity for certain drug-related crimes. Those who overdose will no longer face charges for any personal drugs or paraphernalia police find when responding to such a call. Further, the law allows officers from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia to get the training they need to administer an overdose antidote that’s already saved thousands of lives.

The measure is a long time coming: Pennsylvania ranks seventh in the nation in overdose mortality, according to the Centers for Disease Control, but scored lowest among its neighbors on a recent Policy Report Card detailing overdose prevention strategies.

Legal protection for drug users who call 911 is a critical component of such a strategy. Barely half of all overdoses result in a call for emergency assistance despite the fact that most occur in the company of others. It’s not hard to understand why. Addicts tend to avoid the police because police tend to lock them up. Laws like the one Gov. Corbett approved this week are supposed to fix that in the name of public health.

The commonwealth’s Good Samaritan law is far from perfect. For instance, unlike Delaware’s rather expansive law — which provides immunity from arrest, charge and prosecution for a host of drug-related offenses, and includes an “affirmative defense” clause for drug dealers who report an overdose — in Pennsylvania, callers to 911 will only be immune from a handful of possession-related violations (overdose in front of your dealer, or be dealing drugs yourself, and you’re probably out of luck).

What’s more, the law only protects good Samaritans from being “charged” with a crime; under Pennsylvania law they can still be arrested and detained without charges for up to 72 hours. And, citizens seeking protection under the law are required to relinquish their right to anonymity by providing their name to police. This could presumably lead to arrest on an outstanding warrant (not an uncommon thing for a drug abuser to have.)

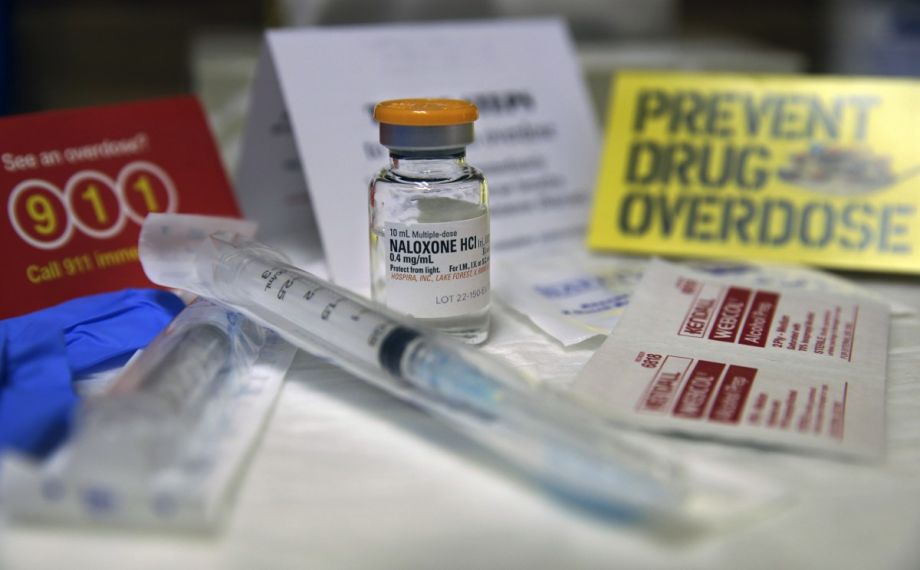

In spite of these weaknesses, drug policy reformers supported the law because it includes a provision for the distribution of the overdose antidote naloxone to emergency personnel, police, and the friends and family of drug users.

“The good naloxone language got tagged onto a not great Good Samaritan bill, so we supported it because we feel we really needed the naloxone language,” explains Alice Bell, the coordinator of the Overdose Prevention Project for the user advocacy group Prevention Point Pittsburgh.

Both Prevention Point Pittsburgh and its counterpart in Philadelphia have run small but successful naloxone training and distribution programs since the mid-2000s. Combined they’ve distributed naloxone to some 2,000 drug users and documented more than 1,500 overdose reversals where the drug was used. Prevention Point Pittsburgh has also provided close to 8,000 inmates with naloxone training through a program it runs in the Allegheny County Jail.

Nationally, between 1996 and 2010 programs like Prevention Point’s led to more than 10,000 overdose reversals, according to the Harm Reduction Coalition.

Bell says the new law will enable the group to significantly expand their program, which until now was only permitted to distribute naloxone to individual addicts with a valid prescription in their name.

Prevention Point Philadelphia will also redouble its efforts to get naloxone into the hands of front-line police officers. While paramedics have long carried the drug, in most cities, including Philadelphia, police officers are not trained or authorized to administer it — despite the fact that they are often the first to arrive at an overdose scene.

Jose Benitez, executive director of Prevention Point Philadelphia, says the Good Samaritan law will make his work a little easier. But the county still needs to approve any changes, as well as the funding to see them through.

Benitez can expect to find a strong ally in the Philadelphia Police Department. Commissioner Charles Ramsey was an early supporter of the Pa. law, and police officials say the department is already laying the groundwork for implementation. The official in charge of that transition, Captain Francis Healy, says he has spoken with city officials about meeting the 60-day window for implementation, with an eye toward distributing naloxone to districts that have the highest rates of overdose first.

“The Commissioner wants to move forward with this as quickly as possible. There isn’t a lot of heavy lifting here, but there are details to work out such as how to acquire and store the drug, and getting officers trained to use it,” he said. “If I could get this done tomorrow I would. It would be one less person dead on the street.”

Healy is not hyperbolizing. By all accounts Philadelphia ranks consistently in the top three for the most pure heroin in the nation. In 2012, the city recorded 497 fatal overdoses, according to data compiled by Prevention Point Philadelphia.

Giving first responders and addicts the tools they need to prevent and reverse overdoses will go a long way to cutting that number down. As for the limited immunity, Healy says his officers care more about saving lives than making arrests.

Advocates like Bell say that if that’s the case, police departments in Pennsylvania should put their money where their mouth is.

“Police and prosecutors could implement this in a much broader way than it is written if they want to,” she said. “They can just say we’re going to put public health first and we’re not going to arrest people [who report an overdose.] The law still allows for the tool of arrest, but I would hope that they will say if we can’t prosecute someone we’re not going to arrest them either.”

Christopher Moraff writes on politics, civil liberties and criminal justice policy for a number of media outlets. He is a reporting fellow at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a frequent contributor to Next City and The Daily Beast.

Follow Christopher .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)