Last week, Philadelphia erupted in a debate over equitable parks funding, marijuana use, and the policing and private management of public space. The spark: whether or not people should be permitted to sit on the limestone walls in the city’s central Rittenhouse Square.

The kerfuffle began Jan. 12, when “No Sitting on Wall” signs appeared and a spokesperson for the Friends of Rittenhouse Square, a private group that manages the historic park, told the press, “Due to continuous vandalism and marijuana smoking, City Officials, Parks and Recreation, City Police, and the Friends determined it was in the Park’s best interest to no longer allow people to sit on the balustrade.”

That agreement had apparently been set in motion by a meeting four months prior, itself prompted by a recent shooting in Rittenhouse Square. Neighbors to the park — located in the highest-income area of the city — had the ear of Police Commissioner Richard Ross to complain about loitering, homeless people and, yes, pot smokers that seemed to concentrate around the walls. Soon a police cruiser was idling in the center of the park nearly every day, and then last week, though smoking both cigarettes and marijuana are already illegal in the park, the no-sitting signs went up.

Public response to the ban was swift and angry. A “sit-on” was organized for Jan. 17, a “Toke Back the Wall” event planned for Jan. 20, and a flurry of articles decried the city’s overreach and misguidedness in banning sitting to curtail public drug use. But then Mayor Jim Kenney seemed to end the ban via tweet.

Regarding Rittenhouse Square, I’m frustrated too. This government is very large and at times things just get by you. Sit where you want. ✌️

— Jim Kenney (@JimFKenney) January 15, 2017

But as architecture critic Inga Saffron pointed out in The Philadelphia Inquirer, the controversy is far from over. The issue at the heart of the conflict remains: A small group of wealthy citizens were able to exert their influence over a public park that draws residents from around the city without any public input, despite the fact that other Philadelphia parks have received far less care and been prone to far more violence.

Indeed, after the ban, the Friends of Rittenhouse Square released a statement suggesting that since the group had recently raised and spent $1 million to restore the limestone balustrades, they should have the right to deem them off-limits. The parks department released its own statement, which read in part, “the walls were not originally designed to be used for seating so this measure will further protect the structural integrity of these iconic park features.”

Those sentiments were shared by Vicky Bayle and Richard Branton, Rittenhouse Square residents and members of the Friends group who were walking through the park during a sit-on Tuesday. Though the mayor had already signaled the end of the ban, supporters had come out to use the space in celebration. Branton surveyed the roughly three dozen people chattering away respectfully on the walls, attended to by nearly as many journalists, and shook his head.

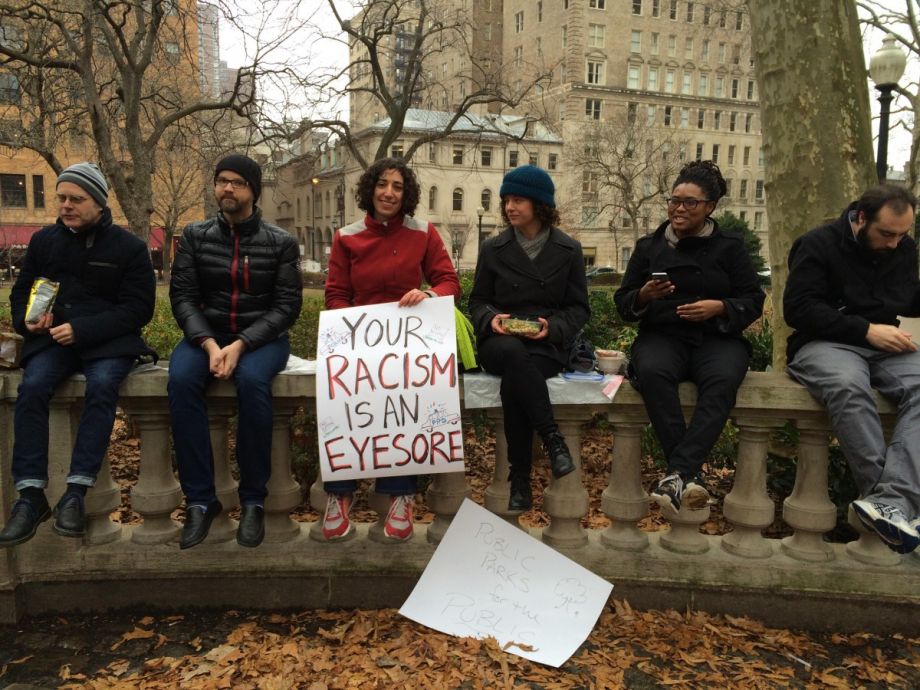

“The problem is not as cute as the media is making it out to be,” he said. Bayle agreed: These mostly young professionals eating their lunches and carrying signs are not the people she wants the police to disperse, those she describes as “drug dealers, people who hang out there day and night, harassing people, intimidating people who walk through there.” When asked if her concerns might not be rooted in racism or classism, she dismissed the idea — the wealthy people who live around the park could be buying drugs there too, she suggested.

Graffiti on Rittenhouse Square walls this week (Photo by Jen Kinney)

But as June Thunderstorm recently wrote in the Baffler, while cigarette smoking bans might be touted under the neutral guise of public health, it’s no coincidence that the people affected are more likely to live below the poverty line. Even when it comes to pot, attitudes are changing. After lifting the sitting ban, the mayor went on to write, “Along with my liberal view of park use, please don’t litter or graffiti or smoke weed so obviously that you scare olds my age.”

After all, being caught with a small amount of pot in Philadelphia triggers just a $25 fine, and police could easily crack down on it without keeping everyone off the walls or parking a cruiser in the center of the square. So there’s reason to believe that outcries over public smoking have as much to do with who is doing the smoking as with the behavior itself.

“I don’t really see how sitting on a wall versus standing next to a wall affects whether you can smoke pot. If they want to smoke pot, they will,” says Coryn Wolk, who lunches in the park and attended the sit-on with a sign that read “Your Racism Is an Eyesore.”

“I’d like them to actually get rid of the cop car and involve people in decision-making about the park and public space,” she says.

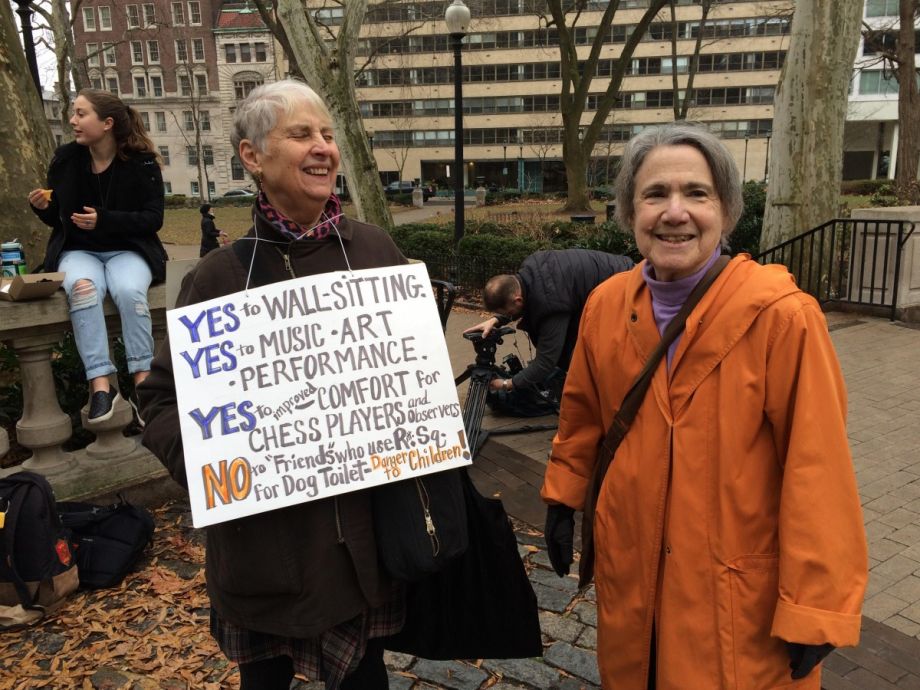

Mina Smith-Segal and Betsy Wice, Rittenhouse residents in support of the sit-on (Photo by Jen Kinney)

Jeff Risom, managing director of urban design firm Gehl in the United States, says the type of ownership over public space that Friends groups and public-private partnerships create isn’t unique to Philly and can be “actually a little bit dangerous.” With cities unable or unwilling to spend the needed resources on park upkeep, that private money is increasingly necessary to maintain usable parks.

“But at the same time if they truly take a sense of ownership, they might exclude groups of people or any type of public life the group deems inappropriate,” says Risom.

If people choose to sit on the walls, though they weren’t intended for it, perhaps they should be seen like desire lines across fields: Attentive designers and parks managers should allow that behavior instead of shutting it down. Risom suggests that for parks like Rittenhouse, which draws visitors from across the city, a Friends group needs to represent all of those users, not just those who can afford to live nearby.

In an article for the New Republic, Saffron floated a similar idea: Rather than conservancies for individual parks, citywide conservancies could direct private dollars to the areas of greatest need, “just like our parks departments used to do,” she wrote.

George Matysik, executive director of the Philadelphia Parks Alliance, hopes that more equitable investment will be one outcome of the Rebuild Initiative, a plan to invest $500 million in city parks, rec centers and libraries, funded by the city’s new soda tax. “Money is going to places that have a lot of inherent wealth,” he says, “but still we see that there are parks and recreation centers in Philadelphia that see 1/100th of the investment that Rittenhouse does.”

One of those parks is McPherson Square, in Philadelphia’s heroin-ravaged Kensington neighborhood. Dennis Payne, who organizes street people and is a member of Friends for McPherson Park (sometimes referred to as “Needle Park”), attended the sit-on. He says it took years just to get street lights turned back on, and now he’s hoping Rebuild will fund security cameras. “We don’t want them but we need them,” he says.

In Rittenhouse, the cop car and anti-sitting signs might only have served to make the park less safe. As Jane Jacobs famously said, and as sit-on organizer Erika Reinhard repeated, eyes on the street are one of the surest ways to provide security in public space. If people don’t feel welcome, they won’t stay, and the park will become less safe for everyone.

“You can’t live your life in fear,” says Reinhard, with a laugh, “especially in Rittenhouse Square.”

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)