Banking is personal for Derek Green. After graduating high school in 1988, he landed a summer internship with Meridian Bank in Philadelphia’s exclusive Society Hill neighborhood. Every summer during college, he’d come back to Meridian to work at a different branch, and the bank hired him full-time after graduation. He specialized in small business lending, and at one point he was assistant branch manager at a branch across from Joe Frazier’s gym, in the heart of historically redlined North Philadelphia.

Corestates Bank acquired Meridian in 1996. Two years later, Wachovia Bank acquired Corestates. It wasn’t long after that Green left banking. Larger banks preferred the efficiency of credit scores and formulas, and eventually algorithms, to make small business loan decisions. They had no use for small business loan specialists with an intimate understanding of and relationships with local businesses along Philadelphia’s neighborhood commercial corridors.

In the chaos of the 2008-2009 financial crisis, Wells Fargo acquired Wachovia. Wells Fargo today still operates both the branches Green formerly worked at.

Green believes the disparity in access to credit for small businesses between wealthier, whiter areas of the city like Society Hill versus poorer, Blacker areas of the city like North Philadelphia is one of the reasons why Philadelphia has remained the poorest big city in the country. Philadelphia is nearly 44 percent Black, but only 2.5 percent of Philadelphia businesses are Black-owned. The median revenue in Philadelphia for a white-owned business is 14 times the median revenue for a Black-owned business, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. So it’s no surprise to Green that households below the federal poverty line in Philadelphia are disproportionately Black.

Now one of Philadelphia’s at-large city council members, and chair of the council’s finance committee, Green wants to use the power of the city’s own deposits to help close that disparity. On October 5, the finance committee held an online hearing to discuss the findings of an independent report commissioned by the City of Philadelphia that studied the feasibility of a city-owned bank that would hold the city’s cash and support more small business lending in areas of the city that currently lack access to it. The study found that such a bank would be challenging to set up, but that it would be financially, legally and administratively feasible.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it both more urgent and more difficult for public bank supporters to keep pushing forward in Philadelphia. “When you look at the perspective of what they provided in the study, the benefit and the need, historical context from a lending perspective, and now looking at the negative impact that COVID has had globally as a health pandemic and also economically, particularly on small businesses and Black and Hispanic businesses, COVID has only enhanced that,” says Green.

Across the country, state and local governments currently hold around $597 billion in deposits. Just about all of those dollars are deposited at private banks, with the lone exception being North Dakota, where the state deposits all of its revenues into the 100-percent state-owned Bank of North Dakota. Local governments may opt to bank there as well, and more than 98 percent of the bank’s deposits come from the state government or local governments in North Dakota.

North Dakota created its state-owned bank in 1919 as a way to use state government deposits in order to increase access to credit for farmers and the agriculture industry. The bank has since evolved to support access to credit for all industries in North Dakota, including the state’s fossil fuel industry. It also provides easy access to credit for local governments, as well as student loans. The Bank of North Dakota today has around $7 billion in assets, and 2019 was its 16th straight year of record net income — some of which it pays back into the state’s general operating budget or into other state programs.

The Bank of North Dakota now serves as a model for efforts around the country to create more public banks — local or state government-owned banks that hold public deposits. According to the Public Banking Institute, around 60 efforts across 32 states are at various stages of considering legislation related to public banks. California passed statewide legislation last year and is considering additional legislation this year. New York and New Jersey, too.

The current Philadelphia public bank efforts go back to at least 2012, with the emergence of the Pennsylvania Public Bank Project, which brought together tenant and environmental justice organizers and networks, business leaders and former bankers, academics, and other public bank advocates like former Public Banking Institute Chair Walt McRee, whom the city council finance committee invited to testify at the hearing on Monday.

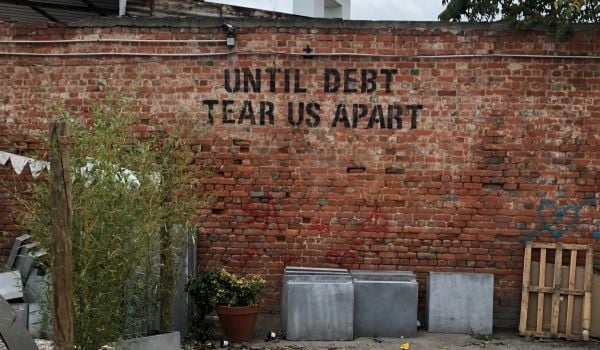

Besides supporting greater access to capital for small business, part of the motivation for public banking supporters in Philadelphia has been the desire to divest public dollars from large financial institutions that repeatedly fall into patterns of predatory activity that disproportionately harm communities of color.

Those earlier efforts helped create fertile ground when, after Derek Green first came into office in 2016, his first bill was a resolution to begin holding hearings regarding public banking. But it still took several more years to find the money to find the funding and conduct a bidding process for an outside consultant to conduct a study examining the financial, legal and administrative feasibility of establishing a city-owned bank.

To oversee the bidding and the study process, the City Treasurer’s Office convened a public bank working group including representatives from the City Treasurer’s Office, Commerce Department, Finance Department, Mayor’s Office, City Commercial Law Unit, the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation, and the Philadelphia Public Banking Coalition — an advocacy group not affiliated with the city.

The New York-based consulting group HR&A won the bidding process at the end of 2019. The group previously conducted a public bank feasibility study for the City of Seattle.

To kick off the Philadelphia study process in January, the working group convened one day of in-person panel discussions to gather early input from an even wider group of voices, from former bankers to cooperative business networks to faith-based groups. Then the pandemic hit.

“I would say we went on pause basically for two or three months before we were able to get everybody’s attention again,” says Andrea Batista Schlesinger, partner at HR&A who oversees the firm’s Inclusive Cities practice, which includes its public banking work.

The working group emphasized early on that their priority was to see a public bank supporting greater access to small business lending, as a way to encourage more job creation, particularly in low-income, predominantly Black and Hispanic areas of Philadelphia. To provide a more concrete sense of what that need is, HR&A combined U.S. Census data with survey data from a variety of public and private sources to come up with an estimated small business lending gap of $840 million.

In other words, small businesses in Philadelphia need an estimated $840 million more in loans than what the current landscape of small business lenders in Philadelphia is able to provide, according to HR&A’s analysis.

“The quantification may be way off, but they put a stake in the ground, and I applaud them for that,” says Peter Winslow, who represented the Philadelphia Public Banking Coalition as part of the city’s public bank working group.

To model whether a Philadelphia public bank would be financially feasible, HR&A needed to first figure out how large it would be. The consultants determined the city would have $255 million available to deposit in a hypothetical public bank. The $255 million comes from the city’s projected year-end general fund reserve balance.

However, Philadelphia’s comprehensive annual financial report, an annual reporting document that every unit of government produces across the country, shows that the City of Philadelphia at year-end had $600.5 million in bank accounts under its control, not to mention hundreds of millions more in “cash-equivalent” accounts that it could choose to move into a public bank.

“We worked closely with the city treasurer’s office on those numbers, and they advised us to use the $255 million,” says Ariel Benjamin, the principal author of the study from HR&A. “It was a conservative figure for us to use to capitalize the bank.”

One concern with a public bank is that government deposits are volatile, with huge inflows at some points in the year and huge outflows at other points. But a true deposit-taking bank has established options to smooth out large inflows and outflows of deposits. It can borrow from the Federal Home Loan Bank system, created during the Great Depression to provide liquidity for savings and loan associations, and now open to banks, credit unions and insurance companies. There’s also the Federal Reserve’s discount window, often seen as a last resort, which is currently lending to banks for as low as 0.25 percent.

Taking the more conservative $255 million in deposits number, HR&A modeled two hypothetical public banks. On top of the deposits, they project the city would provide around $38 million in startup capital — federal regulators require banks to set aside some startup or shareholder capital at all times.

The first hypothetical public bank would operate under the existing constraints in Pennsylvania. As in most states, Pennsylvania requires banks to collateralize public deposits by purchasing basic U.S. Treasury bonds or government-backed securities. The reason is to protect public dollars since state and local governments usually hold deposits far in excess of the $250,000 limit in federal deposit insurance per depositor.

In Pennsylvania, every dollar of government funds must correspond to a dollar in collateral; current local law in Philadelphia requires the city’s deposits be collateralized at 102 percent of their value. Collateralizing $255 million in deposits at the current required ratio would leave only the startup capital amount, around $38 million, available for loans from this hypothetical Philadelphia public bank.

Based on publicly available banking data showing interest income based on different lending and investments as well as income from fees, HR&A estimated the income of this hypothetical public bank to be nearly $9 million. They also estimated anywhere between an annual net profit of $5 million or a net loss of $494,000, depending on how many staffers were needed to run the bank. The true number is probably somewhere in between, but, “I think we found from talking to banking professionals that you can’t underestimate the kind of capacity needed that goes into standing up a banking operation,” says Ariel Benjamin, principal author of the feasibility study at HR&A.

This bank wouldn’t do much lending, but would allow the city to move millions in deposits from large financial institutions to an entity that would at least in theory not exacerbate racist patterns.

But HR&A also modeled out a second hypothetical public bank assuming the state-wide collateralization requirements were lifted. A bank like that would be allowed to put most of its lending into small businesses around the city. This hypothetical public bank would have 55-70 staff, most of whom would be part of approving and managing small business loans. But the interest earned on those loans would be higher than U.S. Treasury Bonds or government-backed securities, resulting in an annual net income of $4.2 million.

This model would require the most work, since it would require lifting the statewide public deposit collateralization requirements or creating an exemption for a city-owned bank. But it is what the working group and Councilmember Derek Green envision.

“We determined a public bank would be feasible if its primary function was to lend to small businesses, if the legal and policy changes that are required were made, and if the bank were capitalized sufficiently to be able to meet the gap for lending to small businesses,” says HR&A’s Batista Schlesinger. “Anything less than those steps, we question whether it’s a worthwhile endeavor.”

Administratively, one essential issue comes up in the report but wasn’t in the scope of the report to model — governance, or in other words how the bank’s oversight, leadership selection and day-to-day decision-making would work. It’s a question of how to ensure political forces don’t get in the way of professional bankers hired to make lending decisions for the public bank on a day-to-day basis. It’s an especially sensitive moment for public institutions and money in Philadelphia, as the city treasurer was recently arrested and charged with multiple frauds.

“When Philadelphia Public Banking Coalition folks go out and talk to community organizations, faith groups, our neighbors, invariably the first thing comes up that most people are concerned about is the corruption issue,” says Winslow. “Where I see the eternal battles coming down the road are going to be issues about governance, and issues about priorities. Managing expectations about a public bank is really difficult, because the power of a public bank is so enormous, people think ‘wow that would be great’ for their issue.”

Green says his next steps are to continue working with Mayor Kenney and his administration on getting more clarity around the legal structure and fiscal implications of a potential public bank.

Editor’s note: We’ve corrected an error regarding the street address of the Meridian locations where Green formerly worked.

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)