U.S. banks are increasingly being held accountable to communities where they do business, thanks to activists — and the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). The power of the CRA is evident in new research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

In CRA examinations, which federal regulators typically conduct every three to five years, banks get credit for loans made in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. That credit helps the banks when they want the government’s OK for business changes such as expansions or mergers. If regulators don’t think a bank is adequately serving communities where it does business, they can deny its expansion or merger applications.

Consequently, the Philadelphia researchers say, banks respond quickly to changes in the way they can get CRA credit, and a 2014 tweak is causing a ripple effect in the Philadelphia area that could affect homeownership in certain neighborhoods.

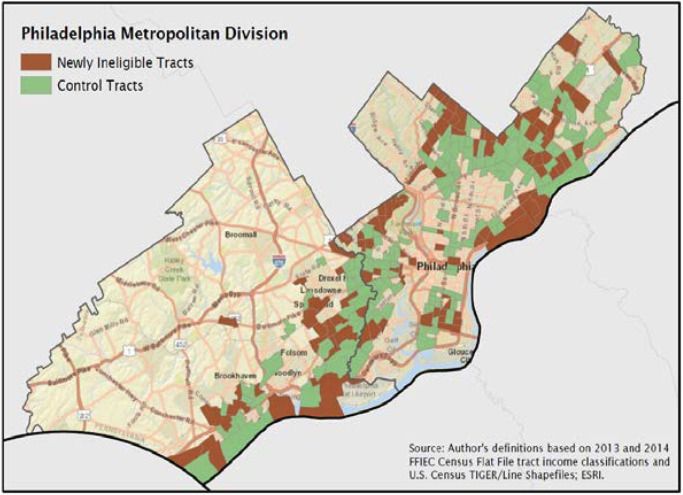

That year, in the Philadelphia metropolitan division — the city of Philadelphia and neighboring Delaware County — 102 census tracts that had been eligible for CRA credit suddenly lost that status.

“The banks,” says Lei Ding, who co-authored a working paper on the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia research, “really reacted to the change.”

The researchers compared Philadelphia and Delaware County census tracts that lost CRA eligibility in 2014 to a control group of census tracts within a half-mile radius and with similar income levels where CRA eligibility did not change in 2014. (The control group tracts either were eligible and barely stayed eligible, or didn’t have it before 2014 and still didn’t become CRA eligible.) Those that lost CRA eligibility have a lot of overlap with Philadelphia’s middle neighborhoods, some of which, while neither very poor nor very wealthy, are struggling with population growth, foreclosures and evictions.)

(Credit: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia)

Looking at the two years prior to January 1, 2014 — when the changes in CRA eligibility occurred — and the two years after, banks dramatically slowed the flow of capital specifically in census tracts that lost CRA eligibility, they found.

Overall, bank lending to homebuyers in areas newly deemed ineligible for CRA credit grew 6.2 percent over 2012-2015. In the control group, bank lending to homebuyers grew 21.7 percent in that same period — reflecting a broader housing market recovery nationwide.

Minority borrowers were hit harder than non-Hispanic white borrowers. Over 2012-2015, growth in lending to minority homebuyers in the areas that lost “CRA status” was 21 percentage points lower than growth in lending to minority homebuyers in the control group. For non-Hispanic white borrowers, that difference was only 11 percent.

If losing CRA eligibility means fewer new homebuyers, the designation change could possibly depress home prices in a census tract, relative to an adjacent census tract — even if the casual observer would see both areas as being in the same neighborhood. Revitalization in Philadelphia could leave some census tracts behind due mostly to the loss of CRA eligibility, as opposed to actual changes in neighborhood preferences.

“There’s many neighborhoods in Philadelphia that have seen massive disinvestment over the years,” says Rick Sauer, executive director of the Philadelphia Association of Community Development Corporations. “We’ve turned the corner about a decade ago, and we’re seeing investment in many neighborhoods around Center City, the river wards and some other areas, but there are still many areas where there has not been the same access to capital as others.”

There could be many reasons why banks increase or decrease lending to certain areas, but comparing similar census tracts nearby helped researchers isolate CRA eligibility as a factor determining how much bank lending activity there was in any given tract. Losing CRA eligibility didn’t mean banks completely stopped lending in a census tract, but it did have this remarkable effect of slowing down the flow of new capital specifically to those census tracts. According to the Federal Reserve Bank researchers:

One possible explanation is that CRA-regulated lenders became slower in increasing their lending capacity, staff training, community outreach, or marketing in newly ineligible neighborhoods during the housing recovery. Another possible explanation is that depository institutions have switched part of their CRA lending efforts from newly ineligible neighborhoods to those neighborhoods remaining CRA eligible, but the results in our empirical analysis suggest this cannot fully explain the observed differences.

They also analyzed the activity of non-depository lenders, which are not bound by the CRA, such as independent mortgage companies. Other research has found that non-depository lenders accounted for 38 percent of all home loans in 2015, triple the percentage in 2007. These lenders now account for 75 percent of FHA-insured loans to low-income borrowers, and are often the only source of home loans for borrowers of color.

While non-depository lenders increased their market share in newly ineligible census tracts — they often promise to fill the gap left by banks — the researchers found that non-depository lenders could make up for about half, but not all, of the decreases in the mortgage lending by CRA-regulated lenders in those areas. Moreover, the researchers write, “with increased lending activities by the non-depository institutions in the newly ineligible neighborhoods, people are concerned about the costs and quality of the mortgage products that these lenders are providing.” FHA-insured loans typically come with a higher interest rate than conventional home mortgages.

“It proves that we really need a law that ensures fair and equal access for working poor people,” says John Taylor, CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, a national network of community- and state-based organizations that makes extensive use of the CRA as an advocacy lever to hold banks accountable. “We haven’t evolved to the point where banks will serve those people not because of the law but because it’s good business.”

The changes to CRA eligibility in 2014 were a result of updating census tract income status using new 2010 census data. While some areas lost status because of actual income growth, in Philadelphia’s case, most that lost it did so because of a clerical change in how the federal government calculates median income for the area.

Previously, the Philadelphia metropolitan statistical area, or MSA, included the city plus the four suburban counties around it, Bucks, Montgomery, Chester and Delaware, and median family income was $76,400.

In the changes that went into effect on January 1, 2014, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) decided to split the wealthier Montgomery/Bucks/Chester (MBC) counties from Philadelphia/Delaware County, creating two metropolitan divisions. In the Philadelphia/Delaware County metropolitan division, the new median family income is $54,200.

To be CRA eligible, a census tract must have a maximum of 80 percent median family income. The new lower median family income is what led to having 102 fewer CRA-eligible census tracts in Philadelphia and Delaware County. The Philadelphia researchers estimate that’s one-sixth of all census tracts whose CRA eligibility changed nationwide on January 1, 2014.

“Yeah, it’s crazy,” says Sauer.

The researchers also found that growth in applications to CRA-regulated lenders from new homebuyers in the control group was 15.5 percentage points higher in 2012-2015 than growth in applications from newly ineligible census tracts in that period. As they also note, perhaps that was an indication that banks increased outreach and lending to lower-income areas that remained CRA eligible. Maybe it means that CRA is now helping banks target the most vulnerable neighborhoods, but it still means a dramatic drop in lending especially to borrowers of color in many areas of Philadelphia that have been historically disinvested. As Sauer, notes, even in gentrifying neighborhoods where overall income has risen, many low-income households have survived decades of disinvestment and may still want a shot at buying their own home in those neighborhoods. Banks can get CRA credit for lending to low-income borrowers regardless of where they live.

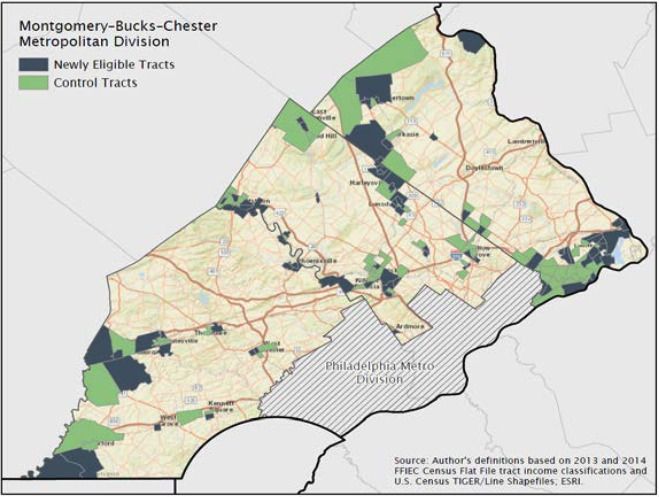

Meanwhile, the new suburban Montgomery/Bucks/Chester metropolitan division got a new higher median family income of $95,400, making 80 census tracts newly eligible for CRA credit. In some ways, this could be helpful, given the suburbanization of poverty.

(Credit: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia)

Banks could turn up the volume of lending in newly eligible census tracts. But the researchers found no statistically significant difference in the volume of homebuyer lending in newly eligible census tracts. “It is possible,” they wrote, “that the credit needs of the borrowers in these neighborhoods in relatively wealthy suburban counties have been well-served through the lenders’ normal course of business without the incentive of CRA.”

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)