From exclusionary zoning policies to trains that stop before reaching areas of racially concentrated poverty, institutionalized racism is literally built into our urban and suburban landscapes. In the Twin Cities, a new method for distributing federal transportation dollars considers the cities’ spatial and economic inequities. Approved last week by a transportation subcommittee of the Metropolitan Council (the agency that oversees planning in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul region), the formula for allotting $150 million assigns points to potential projects — roads, buses, bike paths and even pedestrian infrastructure — based on how they stand to improve racial equity.

It’s desperately needed, according to the council’s long-range planning documents.

“[O]ur region has some of the largest disparities by race and ethnicity of any large metropolitan area in the nation,” a document called Thrive MSP 2040 states.

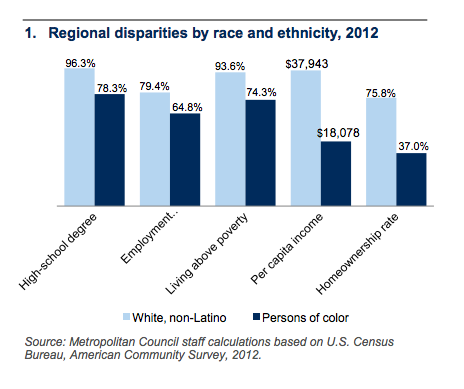

In the Minneapolis-Saint Paul-Bloomington metropolitan area, 25.7 percent of all people of color are poor, compared with 6.4 percent of whites, “the largest such disparity among the 25 largest metropolitan areas.” Unemployment for residents of color is more than double that of their white counterparts, while the “per-capita personal income for black and African American people ($15,336) is just 40 [percent] of the per capita personal income for white, non-Latino people ($37,943).”

Meanwhile, as a document prepared for HUD details, racial segregation continues to intensify even while the region becomes more diverse overall.

“The number of census tracts where more than half the residents were persons of color climbed from 33 in 1990, to 66 in 2000, and to 97 in 2010. Areas where people of color were concentrated expanded from the two central cities to the region’s suburbs.”

“There were cop cars everywhere,” he told the radio program. “And when I walked into the house, these guys had axes and sledgehammers. They were knocking holes in the walls, breaking the windows, tearing up the plumbing — you know, just to make sure he didn’t try to move back in there.”

“They just essentially obliterated the neighborhood,” says Lars Negstad, of the advocacy group Isaiah. The faith coalition works to eliminate “place-based and race-based health inequities” and participated in the Metropolitan Council’s public debate over how to build the new funding formula.

“That story’s pretty well understood here,” Negstad says, explaining that Rondo was an example cited during the process. Planners at the time, he says “were not taking into effect the human cost — how it would perpetuate racial inequality and wall off black neighborhoods from white neighborhoods.”

If their counterparts today don’t consider racial and economic injustices like Rondo, Negstad says, they risk perpetuating them. Urban sprawl and freeway widening projects still disproportionately favor suburban dwellers while harming those who live closest to them.

The updated formula assigns points to projects vying for federal funds in several categories, including safety, usage and, now, equity. Applicants will outline the “impact of transportation investments on low-income populations, people of color, children, people with disabilities and the elderly” along with affordable housing, and their answer will account for roughly 10 percent of their score for roadways, 12 percent for bike and pedestrian projects, and 20 percent for transit.

The scorecard’s emphasis on racial equity stands out, but it’s “not completely unique,” according to commissioner Adam Duininck. Planners looked at regional councils in Denver, Seattle and Kansas City to model the points system.

In Seattle, for example, future projects in the city’s long-range plan are scored in a system that “addresses the extent to which projects improve mobility and/or reduce negative impacts to minority, low-income, elderly, youth, people with disabilities and non-vehicle-owning populations.”

Such plans actually adhere to federal guidelines says Puget Sound Regional Council Program Manager Ben Bakkenta. Several national orders mandate that planning agencies consider environmental justice in project plans.

“But how strong that consideration is — it’s really up to the discretion of each individual agency,” he says. “Something as explicit as awarding extra points, while we’ve done it for years, is not that common around the country.”

In Minneapolis, part of the debate in redrafting the system has been how to measure whether a particular transportation project will have a positive impact on regional equity, Negstad says. But he also sees hope in merely requiring that applicants articulate an answer.

Pretending that land-use decisions are built on a level playing field, he adds, is a fallacy that “leaves out a history of bad decisions all built on hundreds of years of discrimination.”

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)