Depending on which stories you hear, you may see Luther Campbell as either an outrageous boundaries-pushing musician, or a community-minded volunteer with an urbanist bent. On one hand, he’s well known for being part of the explicit booty bass rap group, 2 Live Crew, and he went all the way to the Supreme Court (and won) to fight for First Amendment rights in hip-hop. But another side emerges when you see him in action in his hometown. Since the 1990s, Campbell has given back to Miami by coaching Little League and high school football in underserved neighborhoods.

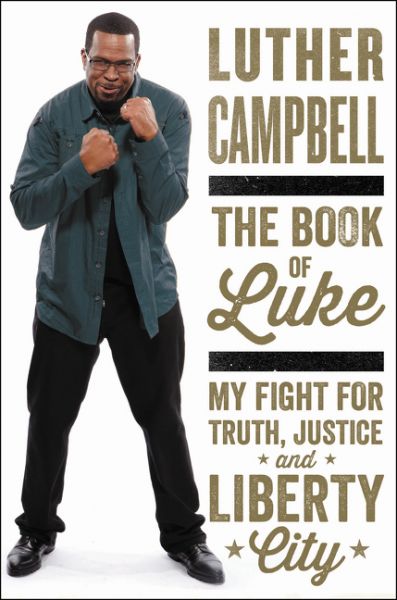

Somewhere in the nexus of these two identities, Uncle Luke (as he’s known in many Miami circles) has also proven that music as well as inclusive entertainment and sports venues in a city are a viable way to support communities and keep kids safe. And he’s documented it all in his book debut, The Book of Luke: My Fight for Truth, Justice, and Liberty City.

Before launching into a braggadocio-laden memoir defending his creation of hip-hop in the South, Campbell delves into Miami’s dirty history. Released in August, it has become a hit, mostly due to how it exposes and contextualizes the usually racist, historical events that led to Miami’s creation.

In a city known for its stereotypes — Miami Vice, cocaine, alligators and the Florida Man Twitter account, just to name a few — many visitors gloss over the sordid details of how America’s favorite tropical city came to be. Campbell, however, uses those stories for the foundation of his narrative. He details how predominantly black neighborhoods like Overtown were gutted by the extension of Interstate 95 bisecting the town in the 1960s, and how his own home of Liberty City — the neighborhood where many of the former Overtown residents moved after being forced out before the road construction — imploded after 1980 riots.

“People are so surprised about what they’re reading in my book. They’re like, ‘I didn’t know people had to be off Miami Beach by six o’clock,’” recalls Campbell, who also ran for mayor of Miami-Dade County in 2011. “And that wasn’t too long ago.”

It was in that tense environment, in 1984 and before 2 Live Crew broke, that Campbell launched a local music event called Pac Jam. Filling his van with deejay gear and records, he and his friends would drive to parks, skating rinks, high school gymnasiums and other venues in these disenfranchised neighborhoods and play music. He did it because if the kids didn’t have anything better to do, he says, they’d have ended up on street corners.

Campbell likes to boast that acts like Poison Clan and Trick Daddy got their start at his Pac Jams. As Trick Daddy, whose real name is Maurice Young, recalls, “When I got out of prison … I went back to the Pac Jam where I grew up and where I was raised. I had a conversation with Luke. He let me enter the contest and I won.”

Campbell emphasizes too how the positive musical gatherings helped wayward youth find stability and safety, as well as learn leadership skills and entrepreneurship in the music business.

Unfortunately, Campbell’s Pac Jams and teen discos didn’t make it out of the ’80s. And in the last 25 years, Miami’s urban core has increased by nearly 15 percent, according to the real estate agency CLRSearch. Foreign investors from South and Central America, and even Asia have built up the city immensely in that time. Many historical landmarks, including music venues like Tobacco Road, have fallen to change. In September, Miami’s 10,000-square-foot multipurpose venue Grand Central (which, in addition to hosting a range of local events, served as the only venue for small- to mid-sized touring bands) closed. According to one South Florida news source, the “shutdown follows a handful of other high-profile nightclub closures in downtown Miami” to make way for luxury condos and retail.

Hector Mendez, owner and president of Studio Center in Miami, thinks that the dearth of appropriate venues contributes to the weak music scene and sense of community within it. Mendez, who grew up in the predominantly Cuban Hialeah listening to 2 Live Crew, first worked with Campbell at Studio Center in the mid-2000s. That’s why when Mendez heard about Girls Make Beats — a local nonprofit that teaches underprivileged young women (many of whom also come from Campbell’s stomping grounds) about deejaying, production, music theory and audio engineering — he donated his entire studio space to the cause.

It’s “one of the coolest organizations that I’ve seen down here that directly affects the community with music,” Mendez gushes.

Examples like Girls Make Beats prove to Campbell and others that music and urban change can be linked in a positive way. In fact, Campbell still believes that the same tactics that he used 30 years ago could be effective today. “No doubt about it!” he exclaims. “I think it would help us.” But, he concedes, “Some of these other facilities need to open up. Have a high school dance at the American Airlines Arena or at Marlins stadium. They got enough rooms in there! Have it at Sun Life Stadium. I mean, I used to do big skating rink parties at the arena that the [Miami] Heat used to play at before.”

Because of increased violence in Liberty City and Overtown, however, he fears too many people are afraid to hearken back to his old, yet proven methods of building community through music. Campbell weighs his options for the future, though, ticking off his upcoming plans for a film adaptation of The Book Of Luke, a website overhaul and reentry into the music business.

“I could see how a lot of people would be scared to open up a club or something like that,” he muses, “but maybe I need to think about doing it.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Hilary Saunders is a full-time freelance journalist and the assistant music editor at Paste Magazine. She’s written about music for publications around the world, and strives to show how the arts can positively impact our cities.

Follow Hilary .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)