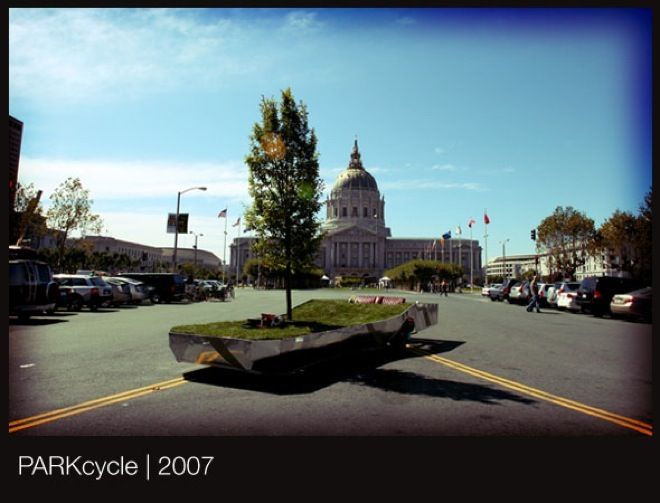

Thought the movement to reclaim city streets was over? Think again. From their studios in San Francisco’s Mission District, the REBAR design collective is churning out interactive, site-specific design interventions that have begun to trigger serious transformations of urban environments, within the United States and beyond. From events like PARK Day (a global initiative in which citizens and artists temporarily transform metered parking spaces into public recreational places) and projects like the Bushwaffle (hot-pink personal inflatables that serve as modular seating structures), REBAR projects place extreme emphasis on public participation that playfully challenge the status quo.

Founded in 2004 by three men from different backgrounds — Matthew Passmore has a law degree while John Bela and Blaine Merker were practicing landscape architects – REBAR is set on making simple yet powerful statements about how and why our cities are designed, and taking them to the streets. Passmore recently took time from his increasingly busy schedule to talk activism, art, and REBAR’s vision for future cities. Below are excerpts of the conversation.

Two themes that seem to run throughout REBAR’s projects are the absurd and the generous. Events like PARK Day are these hilarious ways to re-appropriate public space, but they also provide random strangers with unexpected gifts like shade, food and drink, portable libraries, and more. Why these dual foci of absurdity and generosity?

I think, on the side of absurdity, if you’re trying to make an aesthetic or political statement or some kind of activist statement, humor and absurdity are very effective tools by which to make your message heard. For example, PARK Day is a critical look at how cities are used and broken up, who uses them, and for whom are they designed. In our opinion the city is designed around the automobile. So we could make signs and go to meetings and protest this imbalance that we see in terms of spatial use in our city, or we could take this matter into our own hands and make these things that are silly and open to the public and do so in a way that is generous. Having that sense of humor makes your critical statement more effective.

A lot of your projects are ephemeral installations. Why focus on the temporary?

You have a lot more flexibility in a lot more ways by making ephemeral projects, both in terms of material construction but perhaps more importantly in terms of what you can get away with, what you can say and how radical a statement you can make. If you’re using art or design to question a cultural aspect of society, working temporarily can help you make much more interesting and profound statements.

I would say trying to make some kind of radical critique in permanent form is extremely hard to do. We’re doing more public art now and exploring more and more how to critique established city structures from the inside out.

In articles you have either written or been featured in, the term POPOS comes up often. Can you explain the term and what it means to you in terms of REBAR’s work and focus?

The POPO, which is short for privately owned public open space, is a term that applies to this weird category of space in cities like San Francisco, New York, LA and other major metropolitan areas. What will happen is a developer – in SF it’s a condition of their permit for development –has to set aside a certain footprint of the proposed building as public space.

For REBAR, our projects started with a chance encounter with a sign for one of these POPOs in downtown SF. If you ever see them they’re actually pretty funny – it was a little silver sign, and it says ‘public open space’ or something like that and you see this plaque on this building and you regard the building and its this high rise office building. And there’s this really Orwellian disconnect, in a plaque that says public space on a building that has these kinds of architectural queues in its use and its scale, in addition to security cameras and guards and whatnot, because all of these sites are under heavy surveillance. A lot of them have even more significant barriers to entry, in that you have to go past a security guard to an elevator and then go up to the 15th floor where’s there’s some kind of park.

So POPOs are ambiguously defined. They’re a weird niche in the fabric of the city, loopholes in the code. Investigating these kinds of sites is a theme in our practice. There’s a creative legal dimension to what we’re doing, in terms of looking into legal loopholes or niche spaces that are ambiguously defined in terms of who controls it, what’s allowed there.

Do you think designers and planners have an obligation to be activists?

I suppose I wish designers felt that kind of obligation. I don’t think they do. There are a lot of programs that try to inspire a pro-bono, generous design culture. But I don’t know if there’s obligation. Personally I have obligation to work on the problems that affect and annoy me, to make the world better. But I don’t want to lay too much of the burden of solving of those problems on design either. Design has its limits.

One of the things that comes up around a lot of our projects, because we design public spaces, is that people say we’re going to attract more homeless people and drug users. That may or may not be true, but the fact of the matter is those problems are not going to be solved by design. Those are very complicated and elaborate social justice and public health issues. The solution is not to design a city that excludes parks and spaces for people. Design has a role to play in creating good public spaces but it’s not a panacea. It has its limitations too.

That said, it’s also very often deployed as a tool for the powerful, to create a certain spatial agenda, behavioral agenda of powerful market and profit driven forces. So I think there is, in our practice, a sense of the idea that there needs to be a countervailing force to that. Someone needs to be designing from the ground up, from a community-based standpoint.

Initiatives like PARK Day are growing in interest and participation throughout the world. Is REBAR trying to guide PARK Day as it grows?

With that project, we long ago decided to let it become an open source thing, guided by actors and agents all over the world. Two years ago we started a social network to collect and share the knowledge participants had collected over the years, enabling them to talk to each other. At this point we facilitate people doing it themselves.

What we’re really interested in now is how PARK day can lead to more permanent change within cities. In San Francisco, if you look at the Pavement To Parks Program run by the Department of City Planning, there’s a recent component called the Parklet Program, where there’s an official permit system by which citizens or a community can, on the ground, convert a metered parking space into a plaza for people. So what started as a guerilla action in the form of PARK Day, has now been transformed into a strategic city making process.

Was the Parklet Program an initiative you worked on with the City?

In a lot of ways, the City formed the Parklet Program on their own, but they will openly tell you that it was inspired by PARK Day.

What’s cool about it is this inexpensive way to incubate and test a program. You put this parklet out on the street, which is completely reversible, making it much cheaper than building out a bulb on the sidewalk. If the parklet works, you can always come back later and build it out with more permanent materials. If on the other hand it’s not successful, you can take it out and return the street to being a regular street.

So parklets are an interesting way to test out site program before actually building something more permanent. Now you can go in and get feedback and gather data over time about what’s working, what’s not, and make refinements, so that when you come in and build it, it’s the right design for the site.

There was a recent article in the NY Times about certain European cities – Munich, etc – becoming intentionally less accommodating towards cars. The article made me think of some of your initiatives, like the Parklets. What do you think is the ideal relationship between pedestrians, cars and public transport in future cities?

Making cities more hostile towards cars is the way the issue was framed in the Times article but you could also look at it as de-priviledging cars, leveling the playing field, and equalizing modalities of transportation. For too long cities have been given over to the efficient moving and storage of automobiles. And those are outdated planning principles. They do not apply to the contemporary conditions and contemporary values help by most people who are alive, whether they live in the city or not. There’s a fundamental inefficiency of using a vehicle that weighs ten times that of its occupant. It’s clear that the trajectory those planning principles have put in motion is completely unsustainable.