On the morning of June 25, 2007, Sam, an inmate at Graterford — a maximum security prison less than an hour’s drive from Philadelphia — was feeling pretty good about himself.

A few months earlier, he had participated in a first-of-its-kind telecast to more than 3,000 urban youth gathered together at Community College of Philadelphia. The event was part of an “End the Violence” campaign sponsored by the prison’s newly formed United Community Action Network (U-CAN) — an organization of which he was a founding member. The group came into existence due to concerns over the city’s rising homicide rate, which in 2006 had crossed the 400 mark for the first time in nearly a decade.

The “Old School/New School Call Out” U-CAN organized involved more than 900 Graterford inmates — who spoke directly to the city’s most at-risk youth about the consequences of their actions, and how these young men could avoid taking a similar path. Seated in the audience that day was Sam’s 19-year-old son and namesake, Sam Jr.

Other U-CAN-sponsored “End the Violence” events followed the telecast. In May, the Graterford Prison Chapel hosted a rare memorial in honor of victims of urban violence that was broadcast citywide by a popular local R&B station. The campaign was gaining traction.

Now, Sam and several other inmates were in the prison’s auditorium painting banners for the next campaign, which called on youth in Philadelphia’s most violence-plagued communities to set aside their petty grievances, which all too often lead to fatal consequences.

As Sam carefully formed the words “Squash the Beef” on a piece of poster board, he overheard some inmates nearby talking about a shooting the night before that took the life of the son of a former co-defendant of his who went by the street name “Black.”

The conversation puzzled Sam. Black didn’t have a son. Later that day, an unexpected visit from his sister and daughter cleared the confusion. It was Sam Jr. who had been shot and killed as he sat in a car in the city’s Overbrook section with another teen. (Sam claims the other boy, who survived the shooting, was the intended target of the hit). Unable to process the sudden loss, Sam cut the visit short and returned to his cell where he says he spent a long time contemplating his reflection in the mirror.

More than a decade later, the pain has not dulled.

“When you’re a father, and you commit a crime, your child is your codefendant,” Sam says. “When you go to prison, he goes to prison with you. I let him down by being in here. He needed me out there, but I was in here.”

Sam Jr.’s murder went largely unnoticed outside Graterford’s walls. He was the 196th homicide victim in Philadelphia so far that year (one of two murders reported on that night alone), and his violent death elicited just a few short sentences in the local press. “Numerous gunshots rang out at 8 p.m.,” KYW News reported. “Two young men ages 18 and 19 suffered multiple gunshot wounds. One victim was pronounced dead at the scene of a head wound. … Police [have] no suspects in the double shooting.”

Witnesses to the murder were not talking to authorities, but they were talking to someone. Sam says he knew who killed his son within three days of the crime when he was approached by a group of younger inmates with connections on the street who offered to “‘take care of the situation’” for him, he recalls. His response: Don’t do anything in the name of my son. Let it go. The reply stunned the younger men, who believed that street code dictated retribution. One of the inmates was so visibly frustrated by the stand-down order he was moved to tears, Sam says.

Looking back, Sam now recognizes the moment as pivotal. “I was tested by the death of my son. I truly believe that” he says. “You get tested in so many ways, but when you’re tested with the loss of a child, how are you going to act? Are you gonna go back to a street culture or are you gonna stay true to your word and use it to break a cycle.” Sam chose the latter.

Instead of embracing vengeance, he penned a letter to his son apologizing for abandoning him, and then he began the long hard task of forgiving the men who took Sam Jr.’s life. In the process, he laid the first brick in the foundation of a new program at Graterford that would channel his own experiences of being a father behind bars. He began to plan a 14-week curriculum designed to reconnect men with their children, teach them how to be fathers, and, with any luck, motivate community change, one family at a time. Working with other U-CAN members inside Graterford, Sam willed “Fathers and Children Together,” (F.A.C.T.) program into existence.

F.A.C.T. is far from the only parenting program geared towards incarcerated men or those returning from prison, yet it holds a distinct position among its peers. Its innovative approach didn’t come out of white papers or spring from political working groups; F.A.C.T. was created by incarcerated fathers, for incarcerated fathers.

“This program is particularly unique because it was constructed by a group of men inside who not only understand the needs of fathers behind bars but who hold a significant amount of credibility within the facility,” says Abigail Henson, a doctoral student in criminology at Temple University, who was invited by F.A.C.T. to audit the program.

F.A.C.T accepted its first “cohort” of families in 2012 with the goal of educating incarcerated men that the responsibilities of fatherhood go beyond being a financial provider. To date, a total of 160 men have passed through the F.A.C.T. program. Only two of the 28 inmates released from Graterford since completing the program have returned to prison. F.A.C.T. accepts children between the ages of seven and 17, as long as their primary caregiver on the outside is willing to participate as well. That usually involves dinner or some other activity while the men have one-on-one meetings with their children that are supervised by program facilitators and sometimes a child psychologist. Each cohort begins with relationship training for the men before visits even start. They learn everything from practical skills, like the importance of helping a child with homework, to expressions of fatherhood that may be less familiar to them, such as offering children validations of love and self-worth. “At the end of the day the child is the collateral damage of this system of mass incarceration,” says Ali, another F.A.C.T, co-founder, and one of the program’s facilitators. “Some of the decisions we make as men are bad, but at the end of the day our children shouldn’t suffer because of them.”

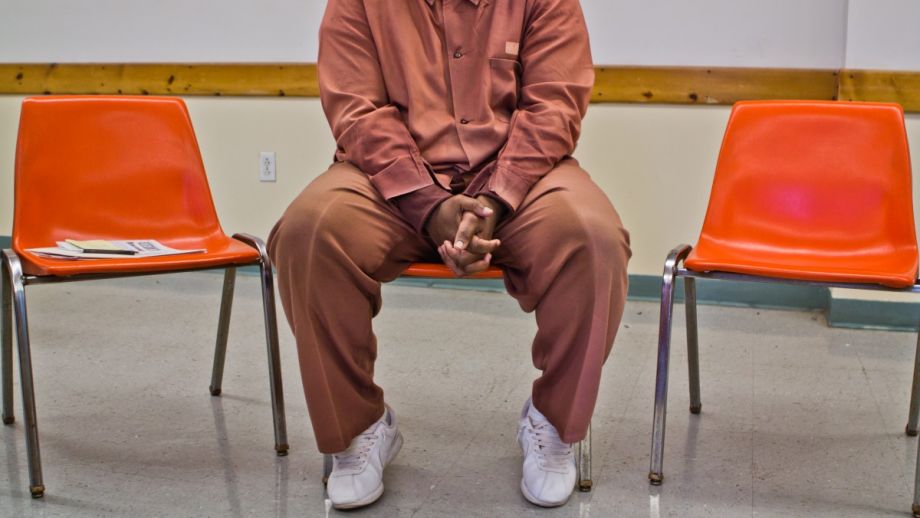

F.A.C.T. members at a meeting inside Graterford (Photo by Kimberly Paynter)

Losing a Parent to Prison

Experts estimate there are more than 2.7 million United States children with a parent in jail or prison. In urban areas, where rates of incarceration tend to be higher, the likelihood of a child having at least one parent behind bars is higher than in most suburban areas. By one estimate used by Pennsylvania state officials, there are 30,000 children with at least one incarcerated parent in the city of Philadelphia alone, and experts say the number is likely higher.

Childhood development experts say that while the impact of a parent’s incarceration varies from case to case, these youth are at higher risk of developing behavioral problems associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. The risk compounds if the child happens to witness the arrest, which is frequently the case. In younger children, studies show that the loss of a parent to incarceration impedes both cognitive and non-cognitive school readiness, essentially handicapping children before they even begin formal studies. A report published in the Journal of Pediatrics finds that parental incarceration also poses potentially serious disruptions to the sleep and eating behaviors of children. In older kids, the anxiety and stress related to parental separation can disrupt learning, and often manifests as anger and antisocial behavior. According to a 2016 study from the Economic Policy Institute, children with incarcerated parents are 48 percent more likely to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than children with non-incarcerated parents; and they are 23 percent more likely to suffer from developmental delays. Children with incarcerated parents, especially sons of incarcerated fathers, are 43 percent more likely to suffer from behavioral problems, researchers found. Unlike other traumas faced by children, the stigma and misunderstanding around crime have created a sort of “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy around the issue of parental incarceration. “With divorce or death, there are traditional ritualized reactions to those things, but kids with a parent in prison face what we call ‘disenfranchised grief’ — it’s like a death without a body and a funeral without a wake,” says Ann Adalist-Estrin, Director of The National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated at Rutgers University–Camden “There is no ceremony, no ritual, no support.”

In highly segregated cities, including Philadelphia — which ranks sixth out of 25 major U.S. metropolitan areas for white-black racial segregation, according to the Pew Research Center — a child’s future remains intricately tied to that of his or her parents. Losing one parent to incarceration effectively cuts that child’s support system in half. As Cornell sociologist Anna R. Haskins writes, parental incarceration “facilitates the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage from father to son,” and plays a role in explaining the presence of racial and gendered differences in early schooling outcomes. “In short,” she writes, “the incarceration of a father affects how ready children are for formal schooling, and the mass incarceration of fathers in this country is limiting the educational potential of their male children.”

Paying it Forward

Sam is a middle-aged African American with small frame glasses and a white beard. Under DOC policy we’re not allowed to tell you his last name, or the specifics of his case. But he is considered a high-profile inmate inside Graterford. Sam is 25 years into a sentence of life without the possibility of parole, meaning that without a commutation from the governor, he’s unlikely to ever walk freely outside a prison again. Sam Jr. was a tearful four-year-old when Sam left for prison, and an emotionally troubled seven-year-old by the time Sam won regular visitation rights and weekly phone calls after a protracted court battle. As his son matured into a young man, Sam did his best to divert him from the lore of street life that captivates so many young men in economically marginalized urban areas. “I told him, look if you want to make a little extra something, you want a little hustle, go up to New York and get you some tee-shirts,” Sam says.

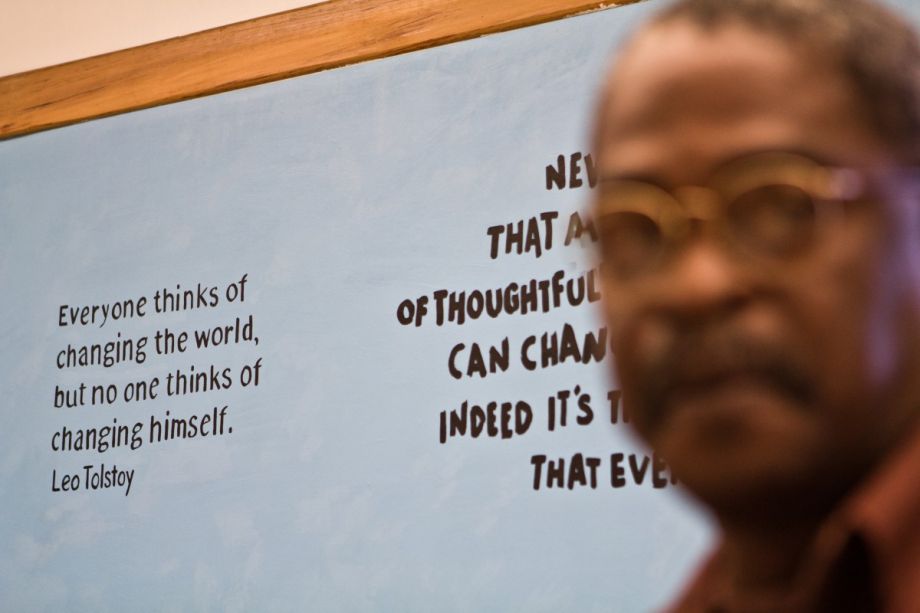

A F.A.C.T. member in front of a white board of inspirational quotations (Photo by Kimberly Paynter)

The night before his death, the two spoke on the phone about a water ice business Sam Jr. intended to start. “I’m gonna be there tomorrow,” he told his father. “Imma be there.” Sam initially conceived the F.A.C.T. program as a means to reconnect incarcerated fathers with children on the outside. Today, his ambitions are bigger, and so is the scope of the program’s work. Through F.A.C.T, incarcerated fathers can receive copies of their kid’s report cards and communicate with teachers. They are encouraged to take an active role in their kid’s lives, ideally before they wind up at Graterford — which is currently the only correctional institution in Pennsylvania that hosts the program. “We don’t want to wait until fathers come to prison,” says Sam. “We want them to get it while they’re still in the community. Now the job is to get this program set up in the community.” This task mainly falls to the handful of paroled F.A.C.T. graduates living in Philadelphia.

On a recent visit to F.A.C.T.’s West Philadelphia headquarters, their dedication was hard to miss. “Going to prison opened my eyes and made me want to do good,” says Dawan Williams, who went through the F.A.C.T. program twice and now serves on the program’s board of directors. “When I got out I wasn’t looking for excuses.” Williams — who has four children, including a son named after him who just turned 13 — was released from Graterford three years ago following a 10-year sentence for robbery. He is tall with a dark complexion and a deep, confident voice that sounds, well, fatherly. “The F.A.C.T. program created a smooth transition so that when I came out here [my kids] just needed my physical presence,” he says. “We had already begun the healing process behind bars.” For Wally Beyah, a F.A.C.T. co-founder who has no children of his own, the mission is about leveraging his years of work with young inmates inside the prison into the role of village mentor. “I started seeing younger, and younger guys coming into the institution and took a concern to that,” he said. I came into the institution at 14 as a lifer. For many years I had a youth group, and I’m familiar with how the youth will act out. I was always interested in youth because that’s when I came into the system.”

Measuring Success

Since graduating its first successful cohort, the F.A.C.T. program has won plaudits across Philadelphia and the region. Despite a shoestring budget comprised of private donations, including a stipend from the Mural Arts Project, the project has grown in scale and shown signs of making a difference. Both the National Conference of State Legislatures and the National Caucus of Black State Legislators have adopted resolutions honoring the success of the F.A.C.T. program and encouraging the proliferation of the program. In 2013, the state legislators passed a resolution urging the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections to consider establishing the program at every state correctional institution. To date that hasn’t happened. One step that may help the program expand is more evaluation of its impacts.

“This program has been around since 2012, and it’s never been evaluated,” Henson says. We don’t have the data to quantitatively say “what kind of impact this has on the children or if its enduring.” Metrics aside, the researcher says she has personally witnessed kids who went from failing grades to the dean’s list after participating in F.A.C.T. “I’ve never seen a program be so anecdotally successful.” A more comprehensive audit is due out next year, but perhaps the best indicator of impact can be found in the experiences of its graduates.

Back in West Philadelphia, Williams is keeping himself busy working to support the community where he once was considered a threat. “I’m not just looking to save a household, he says. “I’m looking to save a nation.”

This article was produced in collaboration with WHYY with support by the Solutions Journalism Network’s Reentry Project, a collaborative news initiative about solutions to the challenges facing people returning from prison.

Christopher Moraff writes on politics, civil liberties and criminal justice policy for a number of media outlets. He is a reporting fellow at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a frequent contributor to Next City and The Daily Beast.

Follow Christopher .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)