American manufacturing is near extinction and has taken the middle class with it, so the narrative goes. Despite all the hand-wringing and promising stump speeches, there’s no denying that the middle and working class in this country is smaller than it was in the years after World War II, and that the recent recession only exacerbated this.

Indeed, hard data confirms that the U.S. has lost a lot of jobs in agriculture, construction and manufacturing, especially since 2007. We combed through Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) employment surveys dating back to 1994 — as far back as data broken down by race is digitally available — to find exactly how many jobs were lost or gained year to year. It’s not pretty, which you can see in the three infographics below.

First, a caveat: These are estimates produced from survey data. There are bound to be outliers and what some might characterize as miscalculations. (And, sure, some of those manufacturing jobs pay much better than others. But we can’t dispute the importance of BLS data.) As Veronica Nigh, an economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation, told me, “Statistics are only so good at estimating what employment levels are.”

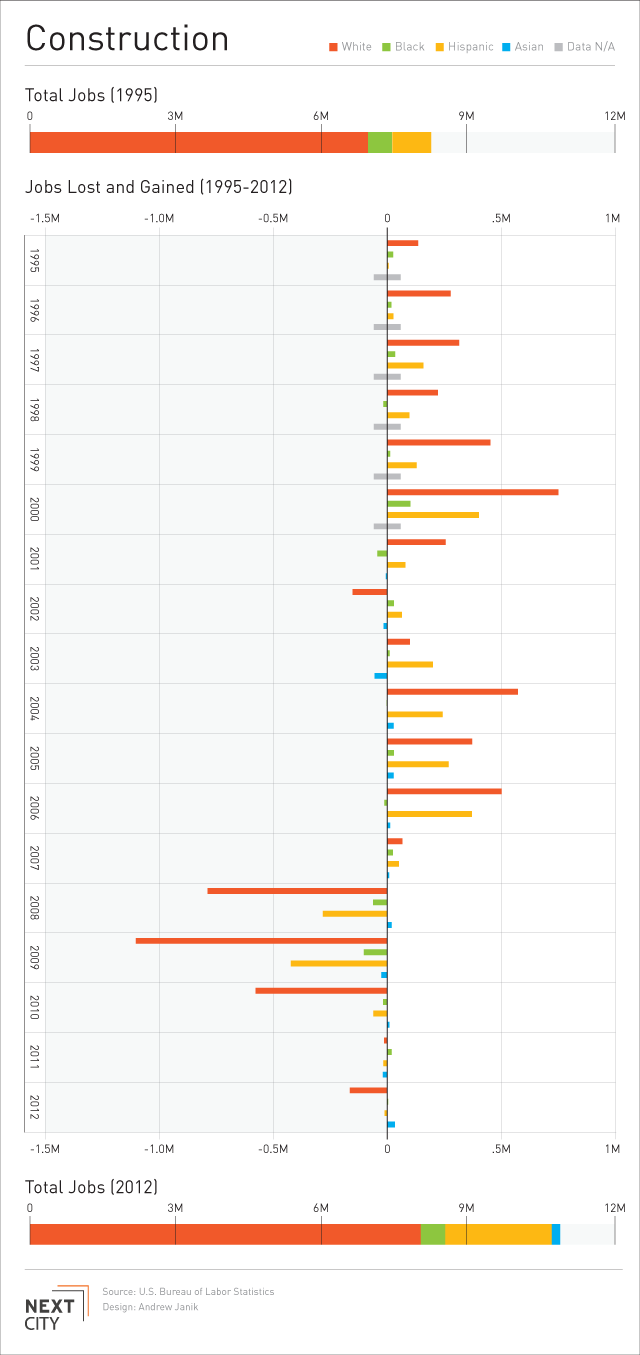

Construction

The housing bubble — think of all those McMansions popping up in suburbs across the country — was good business for the construction industry. You can see below how there was a steady uptick in jobs in the early-to-mid aughts.

“By 2004 construction was really hitting on all cylinders,” said Ken Simonson, chief economist at the Associated General Contractors of America, a trade group. “You had a tremendous surge in construction employment from 2004 to 2006. And even after the housing downturn began in 2006, non-residential kept growing until mid-to-late 2008.”

You might also notice an increase in Hispanic workers. Simonson said there was more discrimination in the 1960s and ’70s, when unions required long apprenticeships closed off to many minorities. That has since changed and Hispanic workers, Simonson noted, “contributed a large part to the increase in construction growth in 2004 to 2008.”

But when the recession hit, construction went on hold. “It was one of the first industries to go into recession,” Simonson said. “With some of the deepest job losses.” Anecdotally, I remember shiny new condo buildings in the rapidly developing part of Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, where I then lived, sitting half-finished for all of 2009 and 2010. The money had dried up and construction crews were out of work as a result.

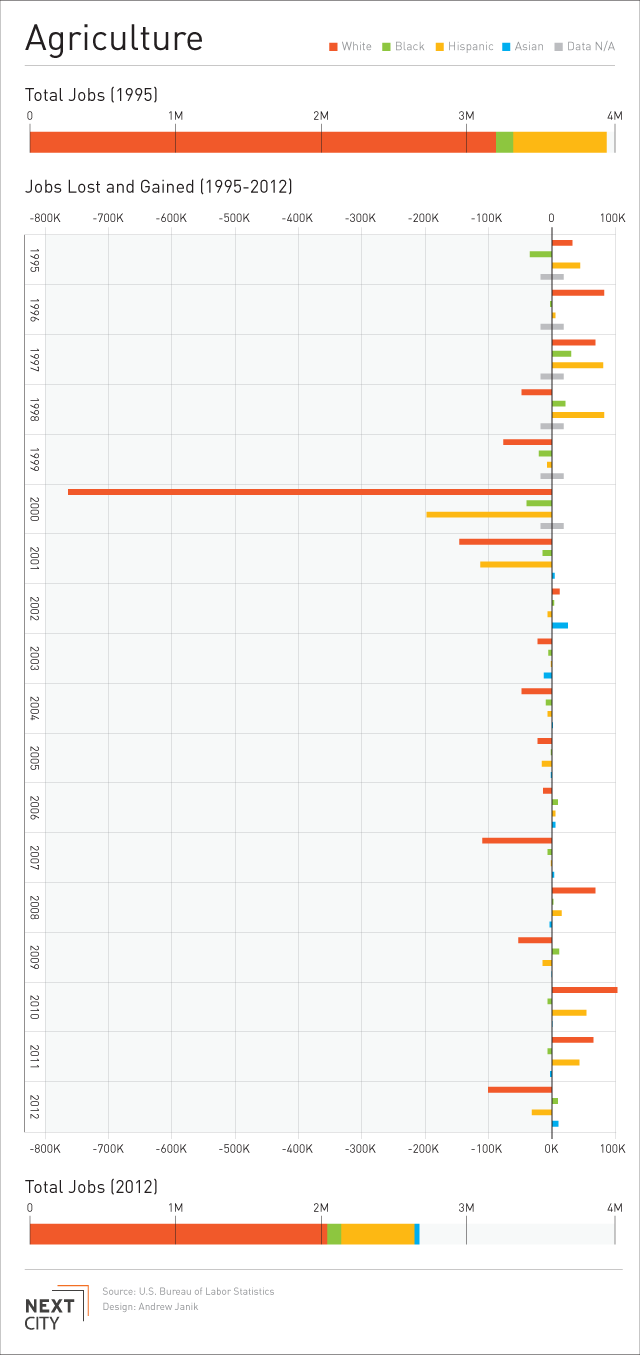

Agriculture

The year 2000, funny enough, saw a severe loss agriculture jobs. Nigh called this a statistical anomaly. “There wasn’t some large event,” she said, that crippled the industry. It had to do with the previously mentioned population estimates, which you can read about here.

What I find most interesting is how the recession barely affected agriculture. While construction and manufacturing saw steep losses, agriculture remained much the same, even seeing some job gains in 2008 and then again in 2010 and 2011. “Agriculture is a bit more stable than other occupations because people have to eat no matter if times are good or bad,” Nigh said. “Agriculture tends to not lose or gain a lot of employment based on larger economic trends.”

On the whole, agriculture has seen a slow-but-steady decline. Nigh chalked it up to an increase in production and the introduction of new technologies. “We have grown more productive as an industry,” she said. “One agriculture employee used to harvest 200 acres. Now they can harvest, say, 400 acres. As technology has gotten better, we don’t need as many employees to do the same amount of work.”

It’s no secret that the agriculture economy hires a lot of undocumented workers. The USDA estimates that about 50 percent of crop farm workers fall into that category. “Undocumented workers are a huge labor source for agriculture industry,” Nigh said, “and therefore do not show up in census data.”

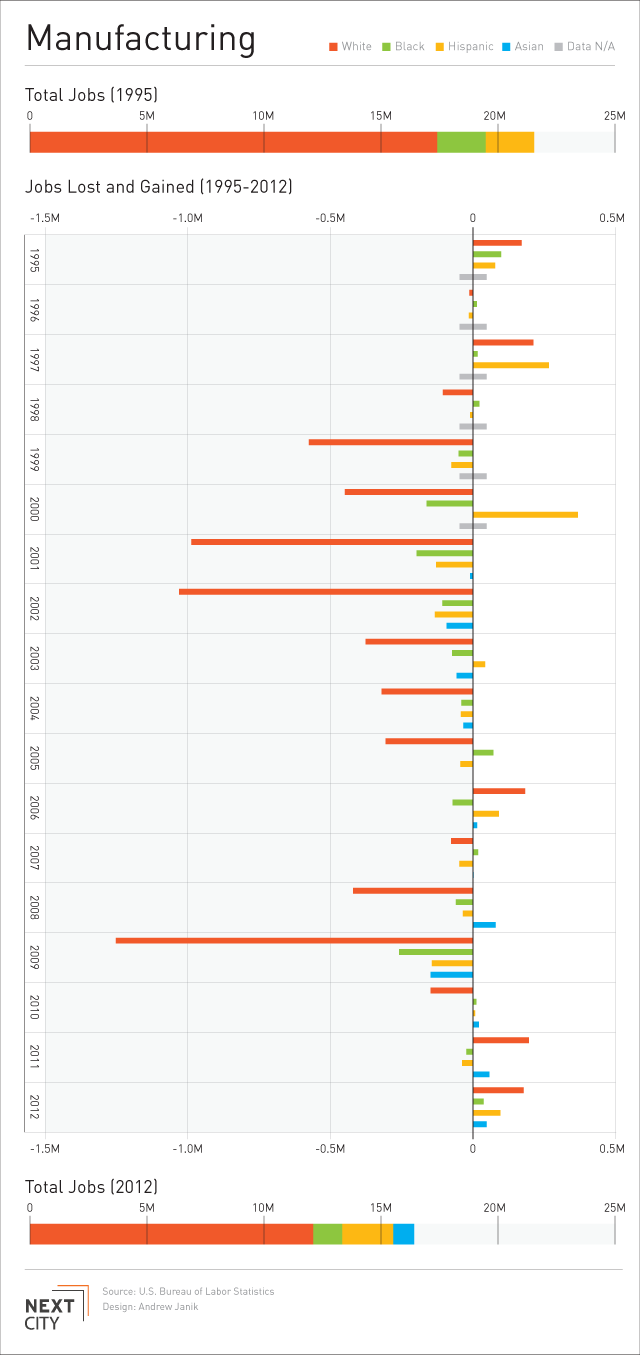

Manufacturing

When we talk about the eroding middle class, we often talk about manufacturing. It brings to mind the depopulated cores of former industrial strongholds: Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Detroit. And, well, the latter part of the 20th century and the start of the 21st have not been kind to the industry.

“The basic story is that factory-sector jobs were on an upward trend from World War II until about 1979,” said Cliff Waldman, a senior economist for the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation. “Then they were on a downward, kind of flattish trend until about 2000. And then in 2000 we fell of a cliff. We fell off an even bigger cliff after 2007.”

A large part of this is obviously because of manufacturers fleeing the U.S. for cheaper labor costs and less overhead offshore. And despite politicians’ penchant for photo-ops with union workers on a factory floor talking about rebuilding America’s middle class, it can’t be understated just how brutally the recession hit manufacturing.

“From peak to trough, December of 2007 to June 2009, manufacturing lost a little over 2 million jobs,” Waldman said. “That’s almost 15 percent of the workforce.” It was a loss of historical proportions. The economy lost nearly 5 percent of its output, while manufacturing lost about 20 percent. “The only time in modern history where manufacturing lost more than 20 percent of its output was the Great Depression.”

But American manufacturing isn’t dead just yet — and no, we’re not talking about the bearded guy down the street who manufactures buttons for small runs of hand-sewn denim. The sector did see some modest growth in 2011 and 2012, though we won’t have the second coming of the Arsenal Of Democracy anytime soon. “Now we’re seeing some daylight,” Waldman said. “It’s looking a little more promising in terms of manufacturing jobs, but we’re still in a post-crisis circumstance.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Bill Bradley is a writer and reporter living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Deadspin, GQ, and Vanity Fair, among others.