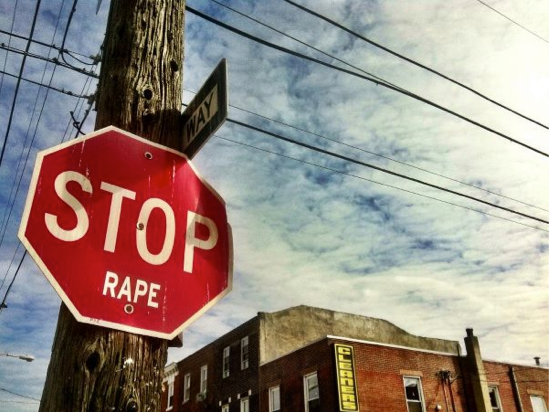

Earlier this year, anti-rape stickers began appearing on stop signs throughout Philadelphia. In multiple neighborhoods, small red and white stickers reading “RAPE” were placed below the word “STOP” so passersby would read “STOP RAPE.” Meanwhile, anti-street harassment stencils have begun appearing on sidewalks in Center City and South Philly.

Both efforts are the work of an anonymous feminist group called Pussy Division, which aims to challenge, according to an email from one member, the “societal norms that perpetuate gender and racial inequality, rape culture, street harassment, and gender-based violence.” The goal is to educate and foment mobilization through street campaigns and social media.

Pussy Division isn’t alone in fighting gender-based violence in the city. In 2011, international anti-harassment campaign Hollaback opened a Philadelphia chapter. HollabackPhilly works primarily through its website, which encourages victims of street harassment — those who experience sexist or suggestive comments, stalking or assault — to report what happened to them and where. The organization then geotags reported instances to create an interactive map showing where the harassment has occurred. This summer, the group also worked with SEPTA to launch a public transit anti-harassment campaign.

High-profile incidents of street harassment in Egypt and elsewhere have drawn international attention to the pervasive problem of gendered harassment in public spaces. While street harassment is widely considered a “low-level” type of gender-based violence, researchers have long known that all types of gender-based violence are connected — whether it be through normative beliefs about gender or whether “minor” offenses, like catcalls or sexually explicit comments, lead to criminal actions such as stalking and assault.

Street harassment may be the most common kind of gender-based violence in the world. Studies have found that up to 96 percent of women surveyed say they have experienced it at some point in their lives. Street harassment is known to similarly menace the LGBT community, affecting perceptions about public safety. A recent online survey conducted in the European Union, for example, found that of 93,000 LGBT people surveyed, half avoided public places for fear of being harassed or assaulted.

Exact figures on the prevalence of street harassment worldwide are unknown and under researched. No universal definition of street harassment exists, and measurement depends on how harassing actions are perceived (street harassment includes a variety of offenses, from comments to assault). Yet no matter what form it takes, street harassment is known to produce profound harms among victims, including depression, low self-esteem and fear.

“We don’t expect that spaces will become instantly safer following our campaign,” wrote one Pussy Division member in an email. The group’s goals are longer term — to educate the public about gender-based violence and to support victims. Rochelle Keyhan, founder of HollabackPhilly echoed the sentiment. She said her group’s efforts to raise public awareness about street harassment and to support victims are the first steps in a process of long-term policy change. “We’re still at the definitional stage,” Keyhan said.

Yet what both groups are already doing — changing harmful social norms — is what experts have long advocated as necessary in ending gender violence.

Credit: Pussy Division via Facebook

Cultural beliefs about gender are known to influence individual action. Research on sexual harassment, for example, indicates that males (who are most often the perpetuators of sexual violence and street harassment) are more likely to harass in groups than alone. Furthermore, the likelihood of whether a young man intervenes in a case of sexual violence is largely influenced by what he believes his peers to believe, even over what he believes himself.

HollabackPhilly runs workshops with high school and college students, delivers public lectures, and has worked with about 700 people in the last three years. Discussions focus on street harassment and gender-based violence, including LGBTQ issues. The Hollaback website, meanwhile, creates a space that validates victim experiences where no other support system may exist.

Additionally, the site creates a strong sense of community. Visitors from 65 participating cities can link to the central Hollaback platform and respond to instances of street harassment in different places, comparing reported incidents elsewhere to their own experiences.

In New York City, Hollaback has already partnered with the city council to link information collected on its website to agency officials. Data collection is intended to direct future policy action on street harassment. Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, Hollaback is working with community leaders and city workers to plan the first-ever U.S. citywide safety audit, a neighborhood exercise in which participants report on safety where they live. The audit is set to take place on the same date, at the same time, in 2014.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that these campaigns are already making a difference. “At least once a month, we receive an email saying that our work made [a victim] feel less alone or stand up to their harasser,” Keyhan said. “[Hollaback] gave the person ownership of… public space and let them feel welcome, even if someone tried to take that away.”

Via Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, Pussy Division has received an “overwhelmingly positive response” to its STOP RAPE campaign. One sexual assault survivor sent a message to the group saying that she felt the stickers are “a way of reclaiming the space for survivors.” She told also the group that “the project unburdened survivors like herself from the responsibility of stopping rape and presented the problem as one that the entire community needs to address.”

At present, Pussy Division is working to establish partnerships with other feminist groups in order to begin conversations about sexual violence and gender non-conformity, including violence against trans women of color.