In late summer, against the constant sound of cicadas singing and water rushing, people flock to the Chattahoochee River in Atlanta. People hike under the trees’ shade and wade along the banks.

The Chattahoochee traverses not only metro Atlanta but the entire state of Georgia, so this scene is a common one, especially in the many parks and trails in north Atlanta. But not so in majority-Black south Atlanta. Parks and boat launches along the Chattahoochee all but vanish as the river winds into the city.

There is racial disparity in green space access in Atlanta, and proximity to Chattahoochee access points is no different, says Richard Milligan, assistant professor of geography at Georgia State University.

“If you look at the color line or the racial distribution of communities across that metro region, the access points, when they disappear, [the community] becomes majority Black,” says Milligan, who studies the intersections of race and environment.

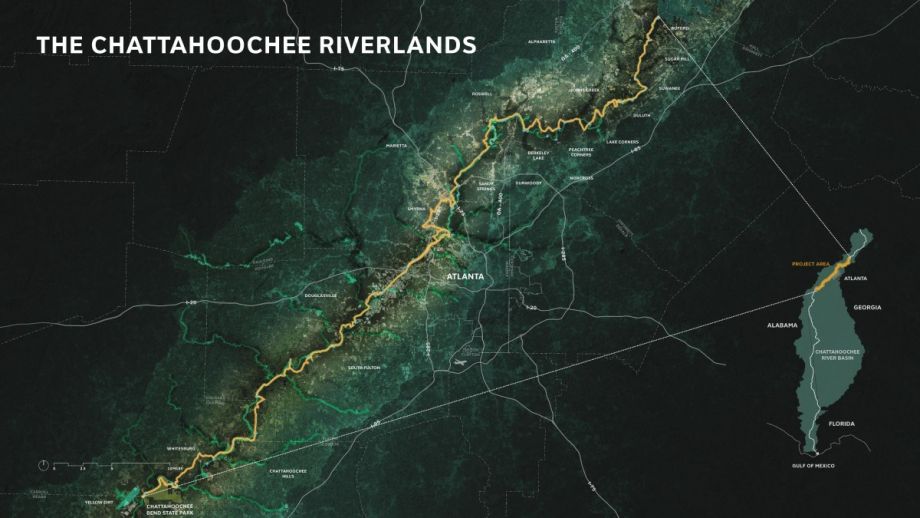

A new study proposes a 125-mile multimodal trail that would cover all of the Chattahoochee River in metro Atlanta, including adding parks and boat launches. (The entire river is 430 miles.) It looks at a variety of factors, including how to increase equitable access to the river in south Atlanta and addressing concerns about gentrification.

The Chattahoochee RiverLands Greenway Study was managed by the Atlanta Regional Commission, the Trust for Public Land, metro Atlanta’s Cobb County and the city of Atlanta.

“Hopefully, the proposed project will not only just generally create a lot more access to the river and different kinds of engagement, but it’ll diminish that disparity,” says Milligan, who was on the design team for the study.

The history of disparate access along the Chattahoochee is complex. The study focuses on a 100-mile stretch of river that lies in metro Atlanta and its outskirts. Almost half of that has been part of the National Park Service since 1978, attracting 3 million visitors each year, says Jason Ulseth, lead advocate of the nonprofit Chattahoochee Riverkeeper. The group, which is dedicated to protecting and restoring the Chattahoochee, lent its expertise as part of the working group for the study.

While the first half of the 100-mile stretch in question is a pristine part of the National Park Service, much of the remaining 52 miles of river was heavily polluted with sewer overflow, wastewater treatment plants and a power plant. It is also the portion of the river that is in Atlanta’s majority-Black neighborhoods.

“In the late 90s, Atlanta was just pulsing huge volumes of untreated sewage into the Chattahoochee basically right about at the color line,” Milligan says.

Because of advocacy work, including a 1995 lawsuit by the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper against the city, Atlanta has invested about $2 billion to improve its sewer infrastructure. That 52-mile portion of river in the city is now the cleanest it has been in decades, Ulseth says.

The placement of polluting sources in Black communities had made that part of the Chattahoochee unsafe for recreation, but now it’s time to open it up, he says. The RiverLands proposals could connect the disparate parts of the Chattahoochee and expand access for residents of West Atlanta.

“All of us here in the city of Atlanta depend on the Chattahoochee River for our daily lives and our water supply, but not all of us get to actually experience it,” Ulseth says. “In West Atlanta, these communities literally have no opportunity to take public transportation or to walk through a public trail and access the river through a public park. Those opportunities have never existed in that area, and this type of vision makes those possible.”

The study acknowledges the risks of gentrification and displacement in previously disinvested areas where new Chattahoochee infrastructure is proposed, namely the majority-Black neighborhoods of West Atlanta. Gentrification as a result of large green-space projects is of particular concern in Atlanta. Construction and activation of the Atlanta BeltLine, a multi use path that circles the city center, caused a spike in real estate prices and the displacement of longtime residents of color.

The BeltLine has imparted lessons about equity to the work surrounding the Chattahoochee, says Walt Ray, Chattahoochee program director for the Trust for Public Land in Georgia.

“Certainly, we learned very quickly that oh my gosh, gentrification is real and it happens very quickly, I think much more powerful than anyone expected,” Ray says. “So how can we learn from that and then what are the examples of organizations that are doing it kind of well?”

Now that the study is complete, the Trust for Public Land is advocating for it and plans to eventually launch a fundraising campaign. It is also exploring a possible idea to create the RiverLands Conservancy, a nonprofit that could help ensure a consistent user experience along the various jurisdictions of the Chattahoochee RiverLands.

The proposals connect 19 cities across seven counties, so Ray expects it will take one or two generations to complete and be financially supported by a variety of federal, state, regional, local and nonprofit sources. The board of the Atlanta Regional Commission voted in August to adopt the RiverLands plan, meaning the 125 miles of trails are eligible for federal transportation funds.

Ray notes that a handful of projects, mostly in the northern half of metro Atlanta, are already being pursued. Meanwhile, as the years pass, this study can serve as a loose framework that continues to evolve.

“The Chattahoochee RiverLands proposes an opportunity now to secure land so that we can prevent it from all being gobbled up by private interests,” Ray says.

In order to avoid displacement, equity needs to remain a focus. Milligan took part in public engagement for the study to discuss how to increase access to the Chattahoochee while staving off environmental gentrification. A host of recommendations came out of this work: engaging communities at risk of gentrification to develop anti-displacement strategies at the beginning of projects, integrating a requirement for displacement avoidance strategies into policies and park funding, and reporting the gentrification effects of any greenway developments.

“Working with visioning this project, you can’t just kind of forget the history and just say, ‘Oh, let’s just create some green space,’ but we have to look at this as a landscape of historic environmental racism,” Milligan says. “Historically, it was devalued. Now the river is much better, but if we just kind of pretend like ‘Oh, we’ll just create access’ and don’t look at the problem of gentrification, the devaluation can be followed really quickly by displacement once the hazards have been addressed.”

Adina Solomon is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta. She writes on a range of topics with specialties in city design, business and death. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, CityLab, U.S. News & World Report, and other national and local outlets.