The Rockaway Peninsula in Queens, New York is home to some of the neighborhoods that Hurricane Sandy hit the hardest. During the storm last October, the streets here flooded completely while the boardwalk along Rockaway Beach was ripped from its concrete mooring and sent hurling into beachfront homes. Because there are no natural barriers to protect the peninsula, which separates the Atlantic Ocean and Jamaica Bay, the area is especially vulnerable to storms.

Now, one urban designer and part-time surfer has an idea to change that.

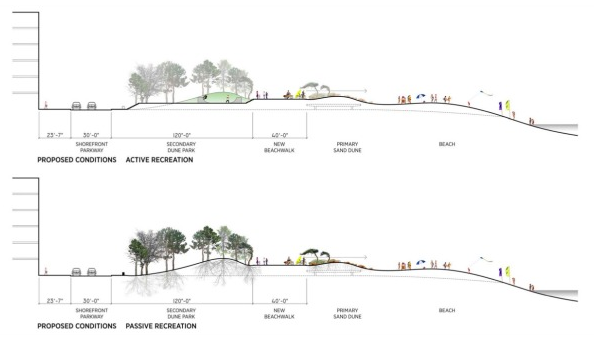

Capital New York reported last week that Walter Meyer, described as a “sometime-Rockaway resident,” wants to slim down the Robert Moses-designed Shore Front Parkway, which runs along a portion of the peninsula’s southern side, to create a barrier of dunes between the ocean and the neighborhood.

Originally built to serve as a connector between Brooklyn and the Hamptons, the Shore Front Parkway generally goes underused today and doesn’t protect the beach from erosion. The road was an obstacle even before Sandy, as those headed to the beach had to trek across its four lanes and median.

Not only does Meyer want to slim the parkway down to two lanes, but in their place he suggests planting a pitch pine dune forest that would further protect the beach during storms. Pitch pine trees have strong roots that bind together creating a natural wall from intruding waters.

Meyers also proposes that a smaller set of dunes be extended out past the dune forest, reflective of a beaches with natural barriers. He told Capital that he has approached the city with his idea and has so far gotten a receptive response.

As Dustin Roasa reported in this week’s Forefront story, neighborhoods in Bangkok, Thailand weathered disastrous floods in 2011 largely thanks to informal networks that stepped in when the government could not. Similarly, citizen-led informal responses cropped up to help several New York neighborhoods recover after Sandy struck. As Roasa writes:

After Hurricane Sandy, when New York was consumed with major tasks like restoring power and subway service, one of the hardest hit neighborhoods, the Red Hook section of Brooklyn, also benefited from one of the most impressive informal responses. A relatively unknown community non-profit called the Red Hook Initiative instantly transformed, in the words of its executive director, “from a small youth development center into a major hub for the disaster relief effort here.”

Governments can be slow to respond to change, and even after a severe storm might rebuild according to the status quo. Rather than wait for the government to act, people like Meyer and those behind the Red Hook Initiative are coming up with their own ideas on how to rebuild and protect their flood-prone neighborhoods.