As a managing partner at Catalyst Opportunity Funds, Jeremy Keele is rejecting around a dozen deals a week that come across his inbox, from developers looking to use the Opportunity Zone tax break to find investors for their projects.

“We’re not going to do luxury condos with a rooftop pool,” Keele says. “We’re just not gonna do that.”

Specific projects, developers and investors have drawn scrutiny around Opportunity Zones for taking advantage of the tax break to support projects that don’t need extra help, or for projects in neighborhoods that are already seeing a lot of investment. But there are also hundreds of Opportunity Zone funds that have formed over the past two years specifically to pool dollars from wealthy investors and make multiple investments on their behalf using the Opportunity Zone tax break.

For those funds, things are just getting started. While not exhaustive, consulting firm Novogradac maintains a list of Opportunity Zone funds, which currently counts 366 funds that collectively aim to raise $66 billion. Of those, 184 funds have raised just $4.5 billion from investors so far.

Although the deadline has passed for some Opportunity Zone tax benefits to investors, Opportunity Zone funds are expecting the tax break to fuel their work for the next few years. Investors have the next decade to make eligible investments in Opportunity Zones, and if they keep their cash invested for at least ten years, any new capital gains from cashing out those investments are tax free — which is why many are worried developers using these tax breaks to finance projects will buy low and sell high. In the world of real estate development, that could mean flipping low-income neighborhoods into luxury housing and luxury retail or offices, or self-storage.

But not all Opportunity Zone funds are the same. Keele’s team is just one of them, and they made three Opportunity Zone investments in December, with more on the way.

“We recognized some of the scrutiny this program was coming under early on, and even if that wasn’t there, we would want to have this authentic commitment to being transparent and really genuinely try to understand the impact that our investment is having in these communities,” Keele says.

Passed as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, the Opportunity Zones legislation itself lacks any community benefit or reporting requirements. At one point during the negotiations around the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, there was a requirement that the Secretary of the Treasury report to Congress on impacts and outcomes of Opportunity Zone investments, including job creation, poverty reduction and new business starts, and other metrics “as determined by the Secretary.” That requirement does not appear in the final legislation.

For Opportunity Zone funds and investors who choose to have some transparency and accountability to Opportunity Zone communities, there’s been a learning curve.

“We’ve had a few investors and funds reaching out to us about how to set up impact metrics in terms of affordable housing units or jobs created,” says Chris Schildt, senior associate at PolicyLink, a national research and advocacy nonprofit. “What we’ve always said to them is, it’s not just about the end numbers but also the process, involving communities in deciding what is needed.”

That said, there’s also a place for impact metrics.

“We’re getting grassroots folks calling us saying they’re seeing an increase in evictions and an increase in investor activity [in Opportunity Zones], and are looking to organize and pressure cities and developers to make sure these investments in their communities actually address community needs,” Schildt says. “That will require some kind of social equity standards for development.”

Keele wants his fund to set an example for others to follow. It’s not the only such example. Some funds have joined up with foundations to share some of the investment risk in exchange for publicly reporting impact data. Some are turning to resources like the OZ Framework, a joint project of the U.S. Impact Investing Alliance, Georgetown University and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The three groups developed the framework after holding multiple roundtables with community development investors, researchers, policymakers and other practitioners.

The OZ Framework is essentially a template that Opportunity Zone funds can use to report publicly on their project portfolios, or for a developer to report on a single project. The framework’s suggested reporting line items include things like jobs created, people hired from low- and moderate-income communities, net new affordable housing units created, percentage of women- or minority-owned businesses leasing space, and demographics of developers leading the projects. Community engagement is also part of the reporting framework.

PolicyLink has also offered its own set of guidelines for leveraging Opportunity Zones in ways that engage communities and are more likely to align with their needs.

“We wanted to set that high bar not just for ourselves but for the field,” Keele says.

Keele’s team started with the OZ Framework, but sought out to build on it in a few different ways — for example, the team also decided to start out looking for developers in small to mid-sized cities in the middle of the country who live in or near the communities where they work or have family and social ties to those communities.

“Going in, our hypothesis was that there were these people out there in these communities, but we didn’t have a long Rolodex, we didn’t know for sure,” Keele says. “Now over the past year we’ve been out in these communities, we’ve proved-out that thesis. There’s certainly not a developer in every one of these communities, but there’s a handful in every middle-market city we’re focused on.”

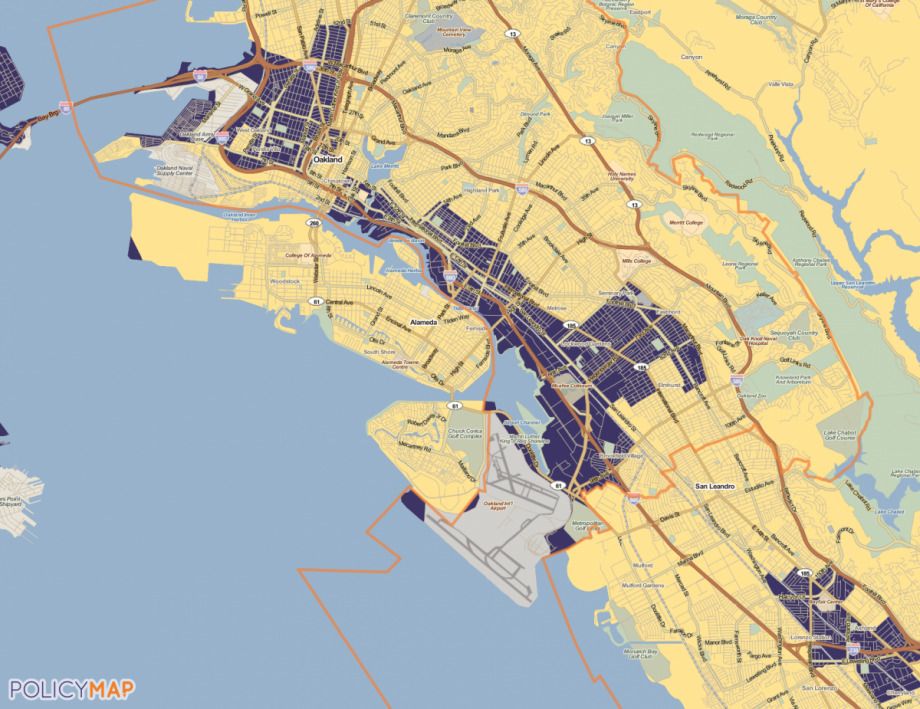

After searching for developers with projects that fit their basic hypothesis, the Catalyst team announced that they had identified 50 projects they felt were worth studying more. The projects span 18 states, totaling some $2.15 billion in project value. But they aren’t planning to invest in every project they find. To prioritize, they came up with an internal process based largely on the overlap between community needs and the aim of each project. To assess community needs, they came up with a scorecard combining 30 available public data sets for things like gaps in access to healthcare, quality education, food deserts, and women- or minority-owned small business growth. The more a project’s intended impact aligns with the biggest gaps, the higher priority Keele and his team assign to it.

Keele’s team also plans to monitor and report changes in those data points for the neighborhoods around the projects they finance.

“We just feel like if you’re investing in projects that create access to things like quality healthcare or education, then you ought to be able to track the second-order effects that investment is having in that community,” Keele says.

It’s a more technical and data-driven approach to choosing investments than the community-driven approach taken by groups like the Boston Ujima Project or the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative (neither of which are leveraging Opportunity Zone tax breaks). But Keele and his team are selling their approach to investors when they also go out and raise money for their Opportunity Zone fund, and investors are buying into it so far.

“Just like any fundraise, we’re not gonna have a hundred percent conversion,” Keele says. “But I think our impact differentiation has been important and meaningful not just to impact investors in our network but to people who consider themselves more mainstream investors but if they feel like they’re also making a positive difference in these communities it’s pretty compelling to them.”

Citing securities regulations, Keele did not disclose how much they’ve raised so far, but their target is $150 million for this first Opportunity Zone fund focused on real estate, and Catalyst is also planning to raise a second that will focus on investing in businesses.

Because of the team’s background, finding investors for the fund has been easier than finding projects. Between Keele and co-founders Jim Sorenson and Patrick McKenna, Catalyst’s senior leadership team has developed or invested in over $6 billion of real estate projects in the United States, as well as founding or investing in over 150 companies worth over $3.5 billion in market value. So the team already had those connections and relationships with “mainly individuals, families, wealth management platforms, the financial advisors who aggregate that kind of capital,” Keele says.

Keele has gone to many of those investors before for projects with some kind of social impact dimension, most notably to invest in a social impact bond — an experimental investment deal where private investors share the risk of funding new models for public service delivery. In Keele’s case, he was a senior advisor to the mayor of Salt Lake City when he led the city through the sale of a social impact bond to finance new models for providing early childhood education to preschool-aged children from low-income communities. So this Opportunity Zone fund isn’t even the most far-fetched deal he’s ever brought to his network of investors.

The main difference with Opportunity Zones, Keele says, has been the focus on real estate. Most “impact investors” up until now have focused on startups or growing businesses that address social problems like climate change or access to financial services.

“Real estate is not a place where at least our group has done much in the way of impact investing, which is interesting because it’s such a powerful opportunity for having an impact,” Keele says.

Other Opportunity Zone funds that may not have connections to impact investors or mainstream investors will have to build them, if they can.

“There’s this really interesting idea for communities to set up their own funds, building on crowdfunding models,” Schildt says. “But the bigger structural problem is that only capital gains income is eligible for the tax benefit.”

Capital gains income comes from the sale of assets that have appreciated in value. In 2017, just 7.3 percent of tax returns reported any net capital gains income. Currently, white households hold an estimated 92 percent of the value of all stocks, 80 percent of the value of all real estate, and 83 percent of the value of “other” assets. The wealthiest ten percent of households account for 64 percent of all assets in the United States.

So the average Opportunity Zone investor is likely to be someone who has stocks or other assets to sell — and that means, statistically, a wealthy white person. Meanwhile, the 35 million residents of Opportunity Zones are 56 percent people of color, with a poverty rate twice that of the country as a whole.

“Opportunity Zones are essentially creating offshore tax havens in low-income communities across our country,” Schildt says. “But we do see promise that there are funds out there that are trying to do something democratic and community-oriented.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)