Occasionally a work of art comes along that is essential to our understanding of the past, present and future of American cities. The new documentary about legendary urban planner Jane Jacobs, “Citizen Jane,” is just such a work.

The rare archival film footage from the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s will deepen your understanding of how and why people like you, me and Jane Jacobs can shape our metropolitan areas. The exciting stories in the movie will renew your faith in citizen activism. Perhaps most importantly, you will gain insights into two individuals who transformed urban policy: Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses. Serving in five New York administrations showed me that their ideas — and the conflict between them — are as valuable today as they were in the middle of the 20th century.

As the film demonstrates, while pursuing life as a journalist, Jacobs became an activist in the mid-1940’s. She developed a philosophy that she outlined in her timeless book, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”. The book made a brilliant case for the importance of busy street life, the need for buildings with different ranges of ages, uses, and occupants. Characterless suburbs “wrote off the intricate, many-faceted, cultural life of the metropolis,” Jacobs wrote. Her insistence on studying the “success and failure in real life” of cities encouraged readers to see what was happening every day in city neighborhoods.

In her writing, Jacobs was thinking of modernist city planners like Robert Moses. Moses began working in nonprofit organizations and soon became a public official. Much of Moses’ work was discredited by Jacobs in her book and opposed as an activist: tearing down slums, creating vehicular arteries, and building high-rise residential buildings surrounded by unoccupied open spaces rather than busy streets. The battle between the two of them — between their visions — defined mid-century American urban planning.

The film accurately presents Moses as only one — albeit the most important one — of Jane Jacobs’ antagonists, not as a cartoon character intent on destroying the homes of thousands of helpless residents. Designers, urban affairs experts and public officials throughout America hailed ‘urban renewal’ as the cure for urban ills. Moses was merely the most articulate and effective of its supporters. As Jacobs explained in “Death and Life,” “decades of preaching, writing and exhorting by experts have gone into convincing us and our legislators that [superblocks connected by superhighways] must be good for us, as long as it comes bedded with grass.” The movie presents many scenes of Moses, long convinced by those experts, explaining why their recommendations are necessary to make our cities great again. That should sound familiar.

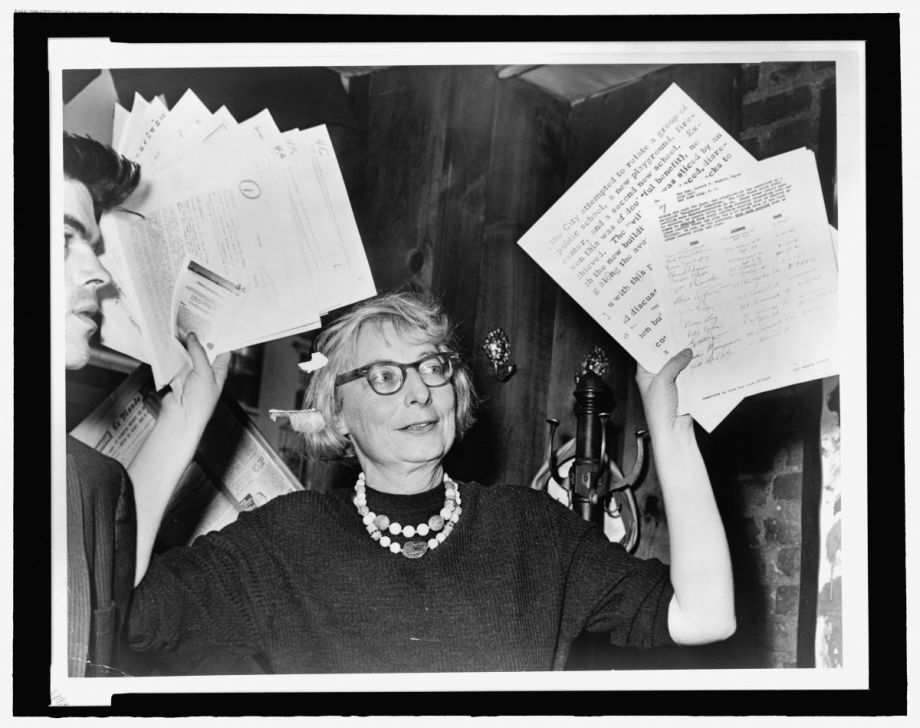

Jacobs organized neighborhood mothers to defeat Park Commissioner Moses’ proposed extension of Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park. It was the start of her life as an activist and an icon.

But Moses wasn’t giving up. As Chairman of the Committee on Slum Clearance, he proposed the clearance of dozens of slums. Over a 12-year period, Moses bulldozed whole neighborhoods, turning property over to both profit-driven and non-profit developers to build superblocks containing residential towers. As urban renewal czar, he supervised construction of almost 9,000 apartments on these sites.

Moses faced strong opposition from site occupants and their elected officials beginning in 1948 when he was appointed to run New York City’s urban renewal program. Even before Jane Jacobs became the program’s active opponent, they succeeded in preventing approval of three of the first five projects and twenty-seven of the fifty-three projects, which Moses announced with great fanfare.

Opponents prevented approval of some of Moses’ projects, even forcing a U.S. Senate investigation of the program, which disclosed scandals in its operation. Similar opposition appeared in every city with an urban renewal program. But it was Jane Jacobs who created the conditions which halted the program. For a citizen with no powerful friends or chest of resources, it was an incredible victory.

Jacobs’ final victory as citizen activist came in the early 1970s when she stopped the clearance of a section of the West Village neighborhood. The Lindsay Administration proposed redeveloping a section of Washington Street, which included the house where Jacobs lives. Her home was not threatened, but her community was. Had the project been approved, it would have destroyed her neighborhood, a neighborhood she showed in “Death and Life” actually demonstrated the elements of good city planning. But Jacobs was victorious. Her opposition forced city officials to replace their proposed high-rise buildings with five story walk-ups whose front doors opened onto the street. The West Village was better off for her efforts, and so all we are.

When you see “Citizen Jane,” you will see, hear, and understand what mid-20th century reformers like Robert Moses thought would improve our cities. Seeing and hearing Jane Jacobs on film, however, will convince you that she was correct in believing that the nostrums of et al actually were prescriptions for killing cities. Most important, you will come away believing that any thoughtful citizen who works at it can prevent the sacking of cities. Any thoughtful citizen can change our cities for the better. That is the legacy of Jane Jacobs, and of “Citizen Jane.”

Next City is hosting a screening of “Citizen Jane” on May 4 in Philadelphia.

Alexander Garvin is currently President and CEO of AGA Public Realm Strategists, Inc., a planning and design firm in New York City that is responsible for the initial master plans for the Atlanta BeltLine, Tessera (a 700-acre new community outside Austin), and Hinton Park in Collierville, Tennessee. Garvin is Adjunct Professor of Urban Planning and Management at Yale University, where he has taught a wide range of subjects, in addition to three courses in the School of Architecture. He is also the author of the book “The American City: What Works, What Doesn't,” published by McGraw-Hill and winner of the 1996 American Institute of Architects book award in urbanism. (An updated, expanded, full-color 3rd edition was released in 2013). He is the author of “The Planning Game: Lessons from Great Cities,” published by W. W. Norton in 2013, among other titles. Garvin earned his B.A., M.Arch, and M.U.S. from Yale University.