EDITOR’S NOTE: “Hear Us” is a column series that features experts of color and their insights on issues related to the economy and racial justice. Follow us here and at #HearUs4Justice.

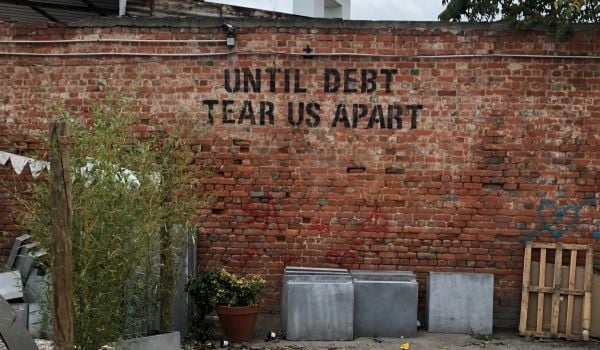

The philanthropic and social sectors seem to have a crisis of conscience every few years regarding equitable funding and decision-making. Specifically, are philanthropists deploying funds in ways that effectively redress racial and economic injustice? Unfortunately, the answer is always unsatisfactory, and then the primary focus becomes new, inventive ways to get more money out the door. We’ve seen it with the rise in rhetoric with impact investing and most recently in the creative use of bonds to finance additional grantmaking related to multimillion-dollar commitments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and racial justice uprisings of 2020. As an organizer of capital, my team at Common Future is working to rebalance philanthropic power and move money to the leaders and groups of color fighting racial injustice.

While there are several laudable racial and economic justice funding efforts throughout the philanthropy sector, the core challenge of philanthropy largely remains unexamined: concentrated power and who has control over financial assets in the first place. Philanthropic gatekeepers maintain strict control over foundation capital and that control is both prioritized and largely guaranteed. Meanwhile grantees—in addition to actually executing the day-to-day work in their communities—must shift, monitor, and report to funders in the hope that they can meet community needs and exist over an adequate time horizon to continue to meet and redress these needs.

Indeed, the amount of money certainly matters, but control over how that money is invested and to whom are equally, if not more so, important.

Let’s take a look at the commitments to racial justice in 2020. Much has been said about these commitments, mainly that we can’t confirm if the tens of millions earnestly pledged during the summer of 2020 has even been deployed or where it went. But the fact that we even have to ask for that accounting is a reflection of the problem of concentrated power. White-led organizations have budgets that are 24% larger and have three times the net assets compared to groups that are led by people of color. Several factors account for this disparity, including interpersonal bias among funders, the lack of understanding regarding the needs of leaders of color, and the arduous application and reporting processes that make it difficult to work with funders in the first place.

The need for a shift in who makes decisions around funding, in addition to the amount of funding available overall, becomes abundantly clear. And yet, much remains the same: 87% of foundation executives are white.

Faced with a generational moment to truly shift power and capital, philanthropy seems to have defaulted to business as usual. While philanthropists may fund organizations that challenge power, the way money is given entrenches their own. And despite various attempts that foundations and other philanthropic institutions have made over the years to diversify their executive and decision-making ranks, these efforts continue to fall short in addressing the myriad systemic challenges that perpetuate racialized disparities in philanthropic funding.

However, several mitigating solutions lie within our reach. At the core of these solutions is the belief that leaders and communities deserve not just access to capital but control of it. How might the philanthropic landscape look if its institutions deprioritized investing in their own perpetuity and instead focused attention on funding programs that perpetuate justice, power, and wealth building in the communities they claim to support? The following ideas are a good place to start.

Prioritize unrestricted funding. We have been both grantee and grantor when it comes to unrestricted funding. Unrestricted funding conveys power, trust, and autonomy. With it, we were able to launch new bodies of work and invest in leaders who are building equitable economic models.

In addition to unrestricted funding, provide grantees with “risk” capital. Over the past two years, Common Future has leveraged unrestricted funding to build risk capital vehicles that allow us to tackle strategic opportunities while maintaining total control of our capital resources. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we were able to quickly launch a rapid response fund to support organizations in the Common Future network. Risk capital allowed us to co-create a shared Character-Based Lending Fund with BIPOC institutions in the Common Future network. Neither would have been plausible if Common Future didn’t have its own risk capital. In the current climate, few BIPOC-led and BIPOC-predominant organizations have risk capital. Funders can play a leading role in changing that dynamic.

Consider endowments. It’s understandable why universities focus on their endowments: these long-term capital commitments allow them to think, plan, and prepare well into the future. As such, they are increasingly becoming ideal for funding the complex issues many organizations are trying to address. Endowments remain out of reach for Black-led organizations; yet as William Foster and Darren Isom note, closing this gap makes addressing pressing social inequity far more within reach.

Cede control of Donor-Advised Funds (DAFs). DAFs were created to provide funding to organizations and tax breaks to donors. But in 2020, only 24% of the money in DAFs was actually donated. What if, instead of those funds laying dormant, organizations were able to move and use that money? Seeding Justice’s Donor-In-Movement Funds (DMFs) aim to do just that, shifting from DAFs to DMFs and connecting donors with organizations in Oregon that work toward justice. In creating this approach, they model how gaining greater control over capital is possible.

With these examples in mind, perhaps the next time we rev up for another conversation on whether money is moving fast enough, we’ll skip the hand wringing and use these guidelines as a blueprint for action.

EDITOR’S NOTE: We have updated this story to correct an error; only 24% of the money in DAFs was donated in 2020.