During the cold, stormy night of January 31, 1953, more than 1,800 Dutch people lost their lives in one of the most horrific ways imaginable. With the wind howling outside, farmers woke to freezing seawater lapping at their beds. Desperate to escape the rising tide, families huddled in attics. They never could have known that the storm surge would rise 3.8 meters above mean sea level.

The high spring tide combined with northwesterly wind gusts of up to 56 meters per second created a perfect storm that became the worst natural disaster Northern Europe had seen in more than two centuries. The death toll should have been much lower, but because the flood occurred on a Saturday night, none of the local radio stations were broadcasting. Church bells were silent. No one knew the water was coming.

Today, water management has become something of an art in the Netherlands, and the delta city of Rotterdam is leading the way. Rotterdam’s solutions to the multi-layered challenges that come with lying four meters below sea level have been implemented around the world in places like New Orleans, New York and Jakarta. In 1953, however, those solutions were desperately lacking. Almost a third of the Dutch coastal areas flooded in less than 24 hours. For a country that had just lost an empire (Indonesia) and was still recovering from World War 2, the flood of 1953 was a hard test of national resilience. More than 72,000 people in and around Rotterdam became homeless in one night.

Civil engineer and project management advisor Stefan Smit recalls the disaster. “The days following the breakthroughs were a continuous battle with the sea to save people. Tides now had free reign in the country. At low tide, dinghies became entangled in barbed wire across the fields; at high tide even more debris was carried inland. Many things happened that people have forgotten. Farmers worked hard to remove the hundreds of thousands of drowned animals from their fields—a gruesome task, but one that was necessary to prevent outbreaks of diseases such as cholera.” Private tragedies are less well known, but almost all Rotterdam families have stories to tell. When Smit’s grandfather returned to work in flooded factory, he lost an arm because of damage to the machines.

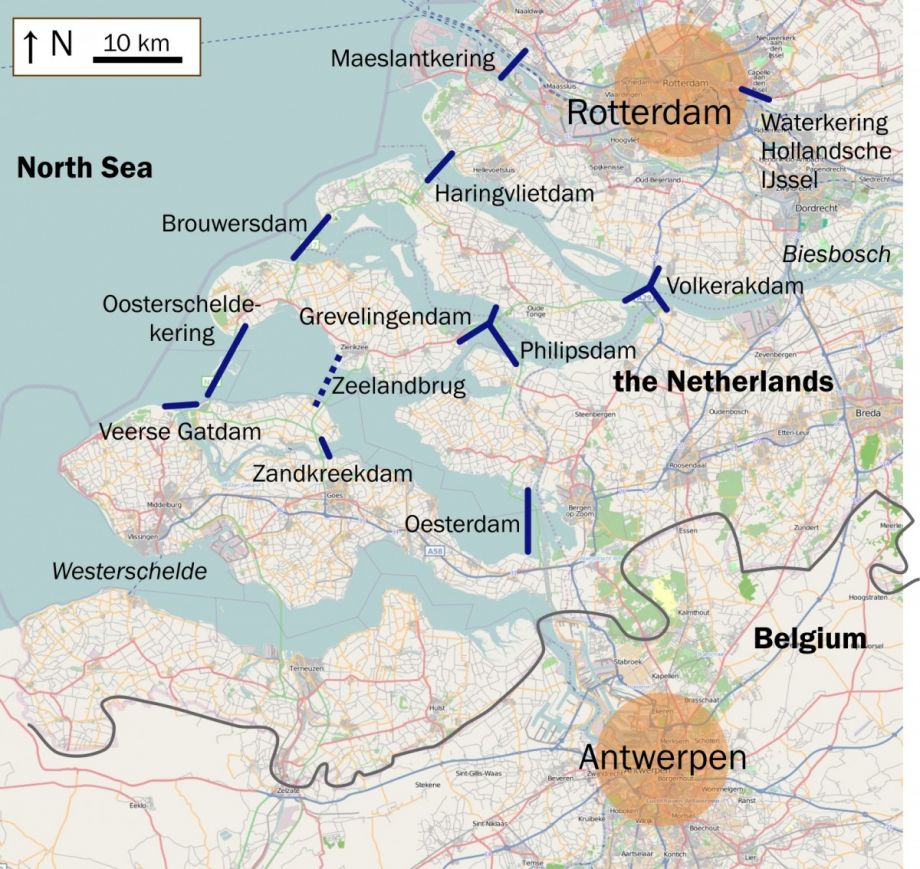

The Maeslantkering is only a small part of the extensive network of dikes, dams, sluices and levees that makes up the Deltawerken. Begun in the aftermath of the 1953 flood and officially completed in 2010, the American Society of Civil Engineers has called the Deltawerken the 8th wonder of the world

Just twenty days after the flood, with most villages still underwater, the first Delta Commission was founded with a public mandate to drain the flooded areas and protect them from future breaches. The choice between raising the heights of existing dykes or closing tidal inlets was quickly resolved – closing the inlets would be cheaper, faster and would allow infrastructural access to remote islands. Rotterdam was the only obstacle standing in the way. Closing the inlet to the Nieuwe Waterweg would cut off the industrial city from all international shipping and trade. While work began immediately on a long list of dams, sluices, locks, levees and dikes, the inlets remained open, and “the Rotterdam problem” was left partially unresolved for nearly forty years. According to Smit, “The first flood barrier in the world, built in the Holandsche Ijssel, was completed in 1958 to protect the polders behind Rotterdam (about six meters below sea level). This dike just barely held in 1953, and if that hadn’t been the case, the flood would have had many more victims.” This particular dike is now legendary. “When the mayor saw a spot in the dike becoming soft, he ordered a skipper to sail his boat directly into the weak spot. The boat ‘plugged the leak’ and the dike held.”

During this time, Rotterdam’s harbor grew to be the world’s busiest port. Finally, in 1991, construction began on the now-famous Maeslantkering. Completed in 1997, the innovative design allows two massive floating arms to automatically close off access to the North Sea when computers predict a storm surge of more than three meters. Each arm is roughly the size of the Eiffel Tower, though more than twice as heavy. When they meet, the arms sink into fitted grooves deep underwater, creating a single, massive barrier. Smit warns, however, that this process can be more difficult than it sounds. “The physical process of closing the two arms takes half an hour. For the arms to sink, it takes another two hours. And of course all of this depends on the right tide conditions; the barrier can only be closed at rising tide.” When water levels are normal, deep-sea ships pass through the barrier toward Rotterdam at a rate of almost 100 per day.

Much has changed for the city of Rotterdam since 1953, but one of the major challenges remains the same. Sixty years ago, as floodwaters surged across the country, a lack of communication left countless people unaware of the impending flood. During rescue operations, communication challenges between various parties slowed recovery and the flow of information. The problem, according to water management graduate student Darja Tretjakova, is that many different governmental organizations are responsible for protecting different—and often overlapping—regions of the city. These parties include Waterschap Hollandse Delta, Hoogheemraadschap van Delfland, Veiligheidsregio, Gemeente Rotterdam and Rijkswaterstaat (two water boards, a regional safety board, the municipality of Rotterdam and the national Department of Waterways and Public Works – and even then, sub-groups within these organizations are responsible for different areas, further complicating the response process). Communication between and within the organizations is problematic. In the event of a crisis, standard operating procedures indicate how the parties should interact, but these methods are never practiced and there are no joint drills. Tretjakova was part of a multi-disciplinary group of students at the Hogeschool Rotterdam commissioned by the Flood Control 2015 consortium to come up with an “out of the box” solution to this disconnect.

The game targets water- and crisis-management professionals and addresses potential scenarios based on real risks for the city of Rotterdam. Photo credit: FloodCom 2013

The Flood Control 2015 consortium includes three knowledge institutes, three large engineering consultancies, an international IT company, a specialized consultancy and a national dike research cooperative. Initiated in 2007, this unprecedented consortium has led to methods for integrating available data from diverse sources, as well as new interactive software that combines and analyses flood-related data. “Smart dikes” are one example: Dikes equipped with sensors are monitored in real time, feeding information back to a central crisis center. Technological advances are combined with a strong focus on the public and increased communication. This is done through a combination of efforts, including an evacuation app developed for smart phones and tablets. The app tells users when to leave and where to go, presenting alternative evacuation routes and real-time information. EvacuAid, a different tool that can estimate the effectiveness of evacuation decisions, helps crisis managers assess information to choose the most efficient plans.

The program’s multi-layer approach to flood safety is groundbreaking. Unlike any other crisis or water management program, Flood Control 2015 addresses challenges related to prevention, spatial planning and crisis management simultaneously. This is key, because to some degree Rotterdam is a victim of its own success. “Many experts mentioned that due to the fact that the Netherlands is so well-protected, and the last large disaster happened in 1953, many people are not aware of the risk of flooding,” said Tretjakova. “Furthermore, to come back to the complexity of the crisis management, the different organizations involved usually practice a ‘disaster response’ only annually or even bi-annually. But of course, that is not enough. There is no pressure, the ‘disaster’ drill is not a random thing, and not all problems can be anticipated.”

The FloodCom game requires players to work collaboratively and think strategically, taking into account real limitations such as budgets, time limits and official regulations. Photo credit: FloodCom 2013

So at the Hogeschool Rotterdam, a Flood Control Game called FloodCom – a so-called serious game – was designed to address “the complexity of the Dutch crisis (flood) management system in combination with a lack of awareness of the risk.”

The game targets water- and crisis-management professionals and addresses potential scenarios based on real risks for the city of Rotterdam. Designed as a tool to aid in cooperation during a potential crisis, realistic events such as dike failures, traffic jams, industrial accidents, electricity failure and sewage overflow are randomized and force players to work together while taking into account their specific capacities. For instance, Rijkswaterstaat is the only organization involved in the process with access to boats; that means they can deal with potential problems along the river. Although specifically designed for Rotterdam, the FloodCom group is now redesigning the game for other delta cities. Other products developed under the Flood Control 2015 project have already been exported to flood-prone areas of the United States and Indonesia, like the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority, which has already integrated the project’s Levee Information Management System (LIMS) module and the Hurricane Risk and Safety Module to help streamline decision-making during a crisis.

The next step for the consortium is the development of a dynamic new collaboration called the International Network for Smart Flood Control (INSFC). The INSFC will push the outputs of the Flood Control 2015 program forward and create a shared, international platform for improved flood defenses around the world.

Although it’s taken a while, Rotterdam has learned from the devastating flood of ’53. Recent advances in flood risk prevention and crisis management make this city a global example of preemptive solutions to catastrophes that are occurring more and more frequently. As sea levels rise and climate change brings more extreme weather, these innovations will need to be deployed to other vulnerable delta cities around the world. For Rotterdam, water management is the most urgent issue the city faces, but not everyone realizes just how critical this issue is. Hopefully, if the work of the Flood Control 2015 group succeeds, most people never will.