In San José, California, thousands of residents have come to rely on the government eviction moratoria, enacted due to the pandemic. But after September 30, the state’s eviction protections will very likely expire. Across the state, roughly 753,000 households, who collectively owe over $2.8 billion, are at risk.

San José city officials were well aware that the end of the eviction moratorium would require residents to provide months of back rent to landlords or risk losing their homes. That’s why they’ve been working since February to build a digital tool that helps connect tenants with rental assistance. Rental Assistance Finder is expected to launch to the public soon.

“A big theme from COVID-19 is that this health emergency has demanded flexibility and adaptability,” notes Guadalupe Gonzalez, an analyst with the city’s rent stabilization program who was part of the project. “After the eviction moratorium ends, we’ll see what the needs are and keep providing the assistance. We’re trying to keep adapting to meet the needs of our community.”

The effort was a part of The Opportunity Project for Cities (TOPcities), an initiative that brings together community leaders, city government, and volunteer technologists to build data-driven solutions to challenges residents face in the fallout of the pandemic.

The nonprofit Centre for Public Impact and the Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University brought on two cities — San José and Saint Paul — and helped them build a team for an 18-week “sprint” to respond to a COVID-influenced community need. The volunteer technologists came from Google.org, Google’s philanthropic arm.

The San José team knew it wanted to focus on the eviction cliff from the get-go — a July 2020 report already outlined the “eviction time-bomb” across Santa Clara County, which includes San José, and the particularly high risk for “people of color, women-headed households, and families with young children.” The city still had some crucial questions: how much aid did residents need, and how could the city ensure they received it?

“As the lead researcher [with the city], I worked closely with the lead researcher from Google on deeper issues we were trying to unearth during the TOPcities sprint,” says Gonzalez. The team sought public data to identify which residents would be most at risk of eviction, then estimate the back rent owed. It was a difficult task. When compiling data from eviction notices submitted by landlords, team members realized much of the information was either out of date or incomplete. They also realized that eviction notices didn’t offer the full picture, as tenants are often evicted through informal means. So they shifted gears and collected data that might better meet residents’ needs, like existing resources for housing support services.

The team also focused heavily on interviews with city officials, community leaders, landlords, and tenant organizers to “gauge the scope of the problem,” as Gonzalez put it. Crucially, the team partnered with Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County to survey 38 residents experiencing economic distress at local food banks.

“We knew it was important to talk to people already coming for some kind of need,” explains Araceli Gonzales, program director of disaster services at Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County, who led that interview process. Anxiety around housing stability was high, particularly with families and elderly tenants. Interviews also revealed the various barriers in accessing rental aid. The application process was confusing, emotionally taxing and had to be submitted online; that was coupled with widespread government distrust. On the community provider’s end, staff shortages and limited technical capacities hampered their ability to efficiently assist residents with the process.

In the face of these barriers, the team shifted its focus to improving the process of finding and obtaining rental assistance for tenants and landlords. It also became clear that a digital tool would not be enough to address the issue. “The digital divide really surfaced in our research phase,” Gonzalez says. “We learned that pop-up centers … would be important to help bridge that gap.”

In May, the city partnered with Catholic Charities to pilot pop-up eviction help centers. “We didn’t have enough bandwidth for in-person appointments, so we wanted to put ourselves out into the community so residents could drop in and get assistance,” says Susan Castillo, program director of housing services for Catholic Charities of Santa Clara County.

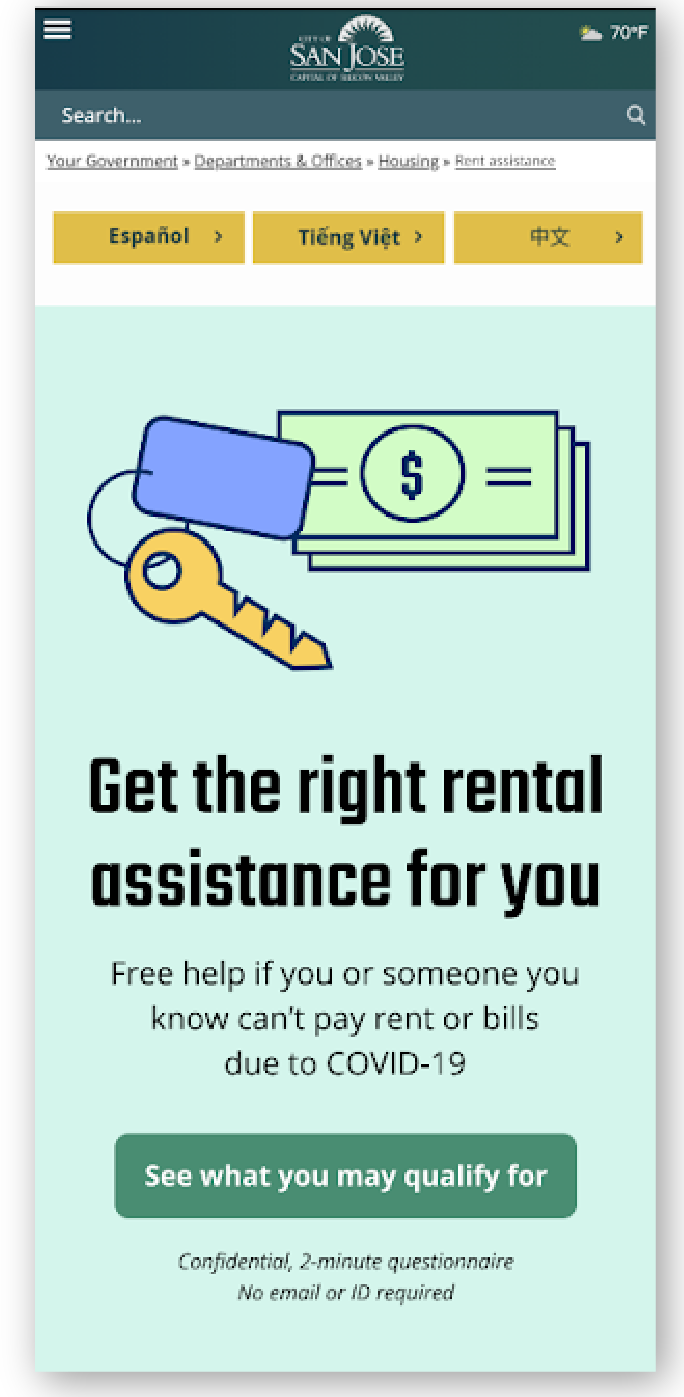

San José's Rental Assistance Finder is an app designed to make the emergency rental assistance process easier to understand. (Image courtesy The Opportunity Project for Cities)

The digital tool came in the form of Rental Assistance Finder, a city app designed to make the emergency rental assistance process easier to understand. The page directs either tenants or landlords through a short questionnaire that calculates the estimated total aid they may qualify for and highlights additional services that may be helpful. The page also directs users to a nearby pop-up and helps them make an appointment.

The Rental Assistance Finder is still in prototype and will soon be made public from both the city and Catholic Charities’ websites. It will also be shared with staff at more than 47 community organizations that work in housing support.

While the team waits on the public launch of the Rental Assistance Finder, they’ve seen immediate impact with the Eviction Help Centers. “Technology is scary for a lot of people … having an actual place is important,” says Araceli Gonzales, of Catholic Charities. “People come because they trust me, and they trust us. We tell people that the city is helping, but they’re helping through us.”

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Emily Nonko is a social justice and solutions-oriented reporter based in Brooklyn, New York. She covers a range of topics for Next City, including arts and culture, housing, movement building and transit.

Follow Emily .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)