The fiscal cliff debacle has mostly crowded out the discussion of gun violence we were supposed to be having after the massacre at Sandy Hook. But the conversation that persisted has crystallized around policy proposals aimed at banning certain classes of weapons and closing the infamous “gun show loophole.”

These proposals surely have their merits, not the least of which is their “gee-whiz” appeal: No one actually needs an assault rifle. Yet each time they are suggested, the discussion of preventing gun violence swerves into an argument about gun control. Gun rights supporters propose more guns for innocents, while gun control advocates mock the idea. In place of debate about (relatively) easy policy changes that would help, or even about hard policy changes that would help, we end up having lots of discussion about hard policy changes that probably won’t do very much good.

Kevin Drum’s new piece in Mother Jones is a stark example of how the conversation about crime and violence is off track. The article summarizes a growing field of literature that finds exposure to lead early in life is associated with violent crime later in life.

Importantly, the effect sizes observed in the literature are substantial. One study finds that “changes in childhood lead exposure are responsible for a 56% drop in violent crime in the 1990s.”

Some of the most interesting evidence is drawn from research on lead exposure in urban settings. Drum cites another study arguing that New York City’s “extensive slum demolition and reduced incinerator lead emissions in the 1960s,” and its 1960 ban on lead paint, are consistent with the particularly severe decline in the city’s homicides between 1990 and 2004. The study provides anecdotal evidence from Chicago as well:

[L]ead paint poisoning in late-1940s slums is also consistent with murders near highways in 1965, when children from those slums were youths living near highways built on slum clearance land. Highway air lead then peaked about two decades before Chicago’s 1992 murder rate peak.

Efforts to limit lead exposure, Drum argues, would reduce violent crime significantly. But interest groups and a need to affirm the power of deliberate human action (that is, police action) have led criminologists and practitioners alike to overlook the lead hypothesis.

Other recent research has pushed back against the notion that the problem of guns and violence is immutable, while also suggesting policy responses other than gun control that would be effective.

In a paper titled “Underground Gun Markets,” researchers Philip Cook, Jens Ludwig, Sudhir Venkatesh and Anthony Braga study Chicago’s illegal gun market and challenge the idea that guns are as easy to purchase as fast food. Underground markets are “thin” with few buyers and sellers. In part, this is because of police activity:

[L]aw enforcement activities appear to matter more in suppressing supply in the gun market than in other underground markets such as those for drugs, in part because the street gangs that are well positioned to deal in guns avoid doing so for fear of attracting police attention, thereby jeopardizing the profits associated with the more lucrative drug trade.

While the authors find Chicago’s ban on handguns to be ineffective in reducing gun availability, they identify a “multiplier” effect to stepped-up law enforcement but warn that that “this virtuous cycle becomes vicious if reversed, which is of some concern given recent cuts in federal funding for law enforcement in general and for gun-oriented activities in particular.”

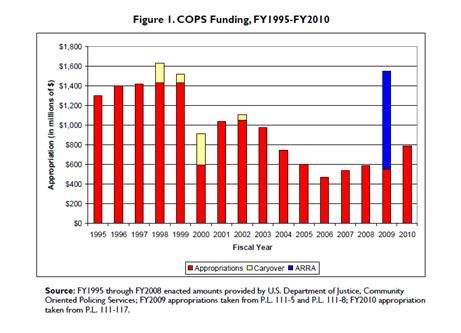

In all of the discussion of gun violence after Sandy Hook, there has been virtually no conversation about increased resources for state and local police departments. In fact, Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS), the federal program that provides funds for local agencies to hire and train law enforcement, is — like most discretionary spending — facing significant cuts even after a decline in funding since 2002.

Source: Congressional Research Service

Indeed, COPS seems to be effective, at the very least in increasing hiring of police officers but also in reducing violent and nonviolent crime (though perhaps not murders).

The policy responses to violence need neither start nor end with the typical calls for an assault weapons ban and a closing of the gun show loophole. Indeed, if Drum’s interpretation of the research is right, these policies may not even be the lowest-hanging fruit. Even in the more traditional spectrum of violence prevention, there seem to be some federal policy responses that might help.