The Housing Choice Voucher Program, formerly known as Section 8, is a program that allows low-income renters to receive vouchers from their local housing authorities that they can use to rent apartments on the private market. It typically pays the difference between what the tenant can afford — 30 percent of their monthly income — and what the landlord charges for the apartment. Aside from public housing, the program is the most important housing assistance that the federal government provides. But it’s not big enough for the demand. Advocates estimate that there are only enough vouchers for a quarter of the people who qualify for them, and voucher waiting lists in most big cities are many thousands of applicants long. Additionally, some voucher holders have trouble finding landlords who will accept them, or apartments that cost close enough to area median rents to qualify for the program.

In 2011, Eva Rosen, now an assistant professor in the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University, moved to the neighborhood of Park Heights, in Baltimore, to research uses of the Housing Choice Voucher Program. The neighborhood is 95 percent African-American, with a lot of low-cost rental housing and a solid base of older homeowners who moved in on the heels of blockbusting and white flight in the 1960s and 1970s, Rosen says. Lately, Park Heights has also become home to many voucher holders — low-income residents who use vouchers from the local housing authority to pay for apartments on the private market. In her new book, The Voucher Promise: “Section 8” and the Fate of an American Neighborhood, Rosen demonstrates that the program provides important material benefits for tenants who receive vouchers, but that it is also constrained by existing inequalities in the housing market and “manipulated by landlords” to secure steady profits on apartments in high-poverty neighborhoods. Rosen describes her book as an “ethnography of a policy.”

Here, Rosen speaks with Next City about her research, the successes and shortcomings of the Housing Choice Voucher Program, and what can be done to improve it. The conversation has been edited.

You write that Section 8 or the Housing Choice Voucher program was created with the dual goal of helping low-income tenants find housing but also giving them mobility and choice about where to live. How successful has it been at those two goals and what obstacles still exist for choice and mobility?

Eva Rosen (Photo by Dustin Andres)

Officially, the goal of the voucher program is really the first thing, to provide people homes who can’t otherwise afford them. When we look at the research on that, it’s doing that really well. It’s helping people stay housed and stay off the street. It’s alleviating overcrowding. It also helps with really basic things, like when you can better afford your home, you spend more money on healthy food for your kids. The second goal is a little bit more of an informal goal, and I think we can think of it more as a hope that policymakers had come to hold. As we think about what vouchers can do that public housing can’t, vouchers offer people a choice about where to live, quite simply. That’s something that public housing never did. If you have a public-housing subsidy, you go where they put you. Public housing tended to be built in neighborhoods that were already pretty disadvantaged and pretty segregated and really didn’t have a lot of jobs and resources.

So vouchers have a couple of theoretical advantages. They allow people to choose where to live. They allow the government to rely on an existing private housing stock that they themselves don’t have to maintain. And they offer tremendous flexibility, and this is flexibility that middle class families take for granted — the idea that if you wanted to move your kid to a different school you could get up and move. If you were having a problem with your landlord you could get out of that lease and move somewhere else. But there’s a number of reasons why it just doesn’t quite happen like this on the ground.

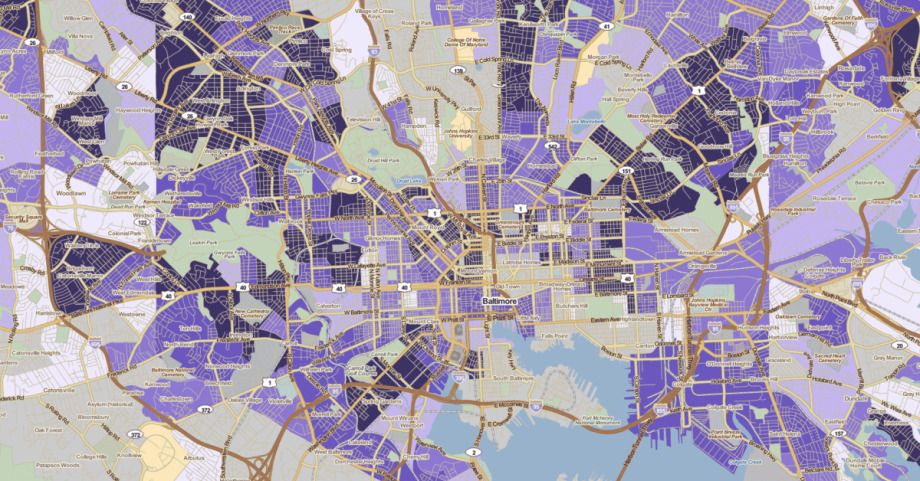

The most simple reason is a supply problem. It’s no accident where affordable housing is located in this country, and you can only use a voucher in a home that’s somewhere around or below the median rent in a particular area. Those homes tend not to be located in super-affluent white neighborhoods or a neighborhood with high-performing schools. We are a country that is incredibly segregated by race and class and so where you can find a rental home is not random. And on top of that, people may not even know where these neighborhoods are. These are not spaces that they may have friends or family in, and they may not even know that they’re safer. There’s an information gap here when people are searching for homes. All groups tend to search for homes in the places they’re familiar with and where they have social networks. So if you want people to break out of that you need to help them learn about places. Then you have problems like transportation. These neighborhoods tend to be located in the suburbs and if you’re a poor person with a job in the city, that’s going to be a big burden if you don’t have a car.

One of the striking aspects of the research to me was the way it shows how the Housing Choice Voucher program is a safety net for landlords as much as it is for low-income tenants. Can you talk about those incentives and how that works?

If a landlord has a property in a more affluent neighborhood, they’re not going to be super interested in a voucher holder, because they’ve got plenty of alternative renters who they perceive to be less risky. They’ve got plenty of demand for their property. In a poor neighborhood or in a more high-crime neighborhood, that landlord is going to have a harder time finding a renter who can reliably pay the rent. We’re talking about people who are poor or who may have very volatile incomes. On top of which, the product in that neighborhood is less nice, it’s probably less well-cared-for, and the neighborhood may have more kinds of problems.

In those neighborhoods, landlords actually have incentives to recruit voucher holders. Unlike a typical market renter who may not be able to pay their rent in any given month, the majority of the voucher holder’s rent is going to be paid by the housing authority. It’s going to be paid really reliably and really dependably, no matter what that landlord does. So it’s very advantageous for landlords in those neighborhoods. And on top of that they sometimes can actually get a premium rate above what we would think of as market rate for that neighborhood. They can actually end up getting more from a voucher holder than they would from a market tenant.

So they’re using voucher-holding tenants to get more out of the property than they otherwise would. And they might have an incentive to buy properties in neighborhoods where the market doesn’t provide a reasonable rate of return but the voucher program does.

Right. And then it provides this incentive for landlords to actually go out and recruit vouchers. So voucher holders become this coveted resource. You see landlords standing outside the voucher office, flagging down voucher holders, trying to get them to come up. So then you have this situation where it’s not really tenants going out and choosing the home they want to live in, which is of course what the whole program is based on. It’s landlords reversing the whole direction of this thing, sort of putting the program on its head, and saying, “I’m going to go and find my voucher tenant and figure out how to convince them to come to this property.”

And there are some vulnerabilities. Voucher holders, while they have this great subsidy, they often can’t come up with a security deposit. How would it be possible for them to come up with that $1,200 for a security deposit? The voucher program often doesn’t help with security deposits. So if a landlord offers to waive the security deposit or reduce it, that’s something that a voucher holder is going to maybe be receptive to, because they may not be able to come up with that security deposit otherwise. So this is where it can become a little bit more predatory, and you can see that it’s no coincidence that voucher holders are ending up in this neighborhood. The landlords are targeting them and recruiting them.

I read in your book that in Baltimore, 94 percent of voucher holders are Black, and you describe a couple different ways that the voucher program and the landlords that use it reinforce racial segregation patterns in the housing market. Can you talk about how both racist discrimination on the part of landlords and existing housing patterns create different outcomes for white and Black voucher holders?

It has a lot do with the geography of housing that predates the voucher program. We have long been a country that has been segregated by race, and that has to do with all the different policies that I mention in the introduction of the book — redlining and blockbusting and predatory lending and all of these things, racial covenants, both official laws and informal practices throughout the history of our country. And then you take the voucher program that is based on these free-market principles and says, Oh look, we have this housing market, let’s just use that and let people navigate with their free will and their choice and this voucher, and it’ll all work out. It’s sort of a naive assumption, because things are already so segregated. Why would we expect that a program that operates under exactly the same rules that we’ve already operated under to change that? Why would we expect people to exercise this choice that historically they’ve never been able to exercise? There are these bigger forces.

The way that I see it play out in Baltimore is you’ve got these two processes. You’ve got exclusion going on in the wealthier neighborhoods and you’ve got targeted recruitment going on in the poorer neighborhoods. The way it works in the wealthier neighborhoods, some of the landlords are very overtly racist in a way that they’ll fully admit to. But a lot of them will say, “I’m not racist, I’m fine with an African-American, but my other tenants on this block where I own three other properties, they wouldn’t stand for this. They would be really uncomfortable if they saw a voucher tenant moving in or even if they saw a Black tenant moving in.” So they’ll often sort of pawn it off on their tenants and that’s where you can see, this is how the market is discriminating. Because if other tenants in this neighborhood or other homeowners in this neighborhood, if they are racist, then the landlord is going to sort of channel that racism and say, “Oh, well, I can’t disrupt the natural order of things, that would be bad for business.” So you see people clinging to these old patterns for the sake of their business.

One of the progressive policies that’s been making the rounds in cities for the past few years is the ban of source-of-income discrimination, which prevents landlords from barring tenants who have vouchers. But in your book, discrimination by individual landlords against Section 8 tenants is hardly the biggest problem. How important are those anti-discrimination laws?

I do think those laws are very important, but they have limitations. The research looking at where source-of-income discrimination laws are put into place shows that they do help. It’s not, maybe, as big as we might have hoped, but they do make a significant difference. The problem is that, again, if you think about a much wealthier neighborhood like Roland Park, there’s not a lot of rental housing there. So even if you say to landlords, “You have to accept a voucher tenant who qualifies,” there may not be very many homes that are going to be below that price ceiling that will qualify. On top of that, there’s ways to manipulate this that aren’t even that hard. If a landlord gets a voucher tenant who comes to the door and says “I’d like to rent your property,” you still have a situation where the landlord can say “OK sure, let me do a credit check.” And then if the credit check isn’t up to the standard that they’ve set, they can still turn that tenant away and they can say it’s because of the credit even though it actually may be because of the voucher. It’s hard on the ground to enforce this kind of law. But I do think it’s an important step.

A lot of researchers and advocates have called for the housing voucher program to be expanded and made available to anyone who qualifies. You write that even though vouchers help low-income people, it’s still a system that allows private landowners to profit off of low-income tenants. So I wonder if you could just say whether you think the program should be expanded, replaced, or changed in certain ways to make it work better? What’s your vision of how this should work?

It’s a program that has flaws but it has a lot of potential. I do advocate for expanding it, with some important changes. I think we really can’t underestimate what it does really well, which is provide people with stable homes to keep them off the streets, even if they’re not living in the most resourced neighborhoods. I think it does a lot. Housing is such an essential thing for people who are trying to keep a job and keep their kids in school and all of that.

The people who had vouchers who I spoke to, they were so grateful for this subsidy and so grateful for the flexibility it offered them, and they really, interestingly enough, many of them felt they had a choice. Even if we can look at it from a bird’s-eye view and say, Oh, here’s all the ways in which your choices are constrained, they really felt that they had choices. And I think that that is a huge improvement over public housing in that way.

I think the number-one solution is actually to make it bigger to help everyone who needs that help. And I think that could also help with some of the stigma that is associated with the program. If more people had it and landlords were more familiar with it that actually might really help. We need to have a federal source-of-income protection law. Because it should not be legal to discriminate against voucher holders. It should be like race or gender or religious background. But if we’re going to do that we need to do something else, called small area fair market rent. The simplest way to describe it is just that if you set the rent ceiling at a more local level, like for example the zip code level or even lower, then what you do is you calibrate rent so that in a more wealthy neighborhood people have more money so that they can actually compete for market rents in that neighborhood, and in poorer neighborhoods you’re then not overpaying landlords for a product that is overpriced relative to that local market.

And then there’s other simple things like there should be more counseling and more information available to voucher holders when they’re going through the rental process. There should be security deposit assistance so that you’re not expecting a family that can’t pay $1,200 in rent to then come up with $1,200 in a security deposit. When you don’t provide that security-deposit assistance you make tenants more vulnerable to those machinations the landlord is going to use to recruit them to properties where it’s most advantageous to the landlord and not necessarily to the tenant.

And the flip side of that, that you mention toward the end, is the idea of investing in these neighborhoods where vouchers are clustered now, with housing and amenities and things like that.

We can’t expect vouchers to solve everything. And we should be critical of the idea that the solution to racial and class inequality and segregation is simply to move poor people out of poor neighborhoods, specifically poor people of color. Why should it be all on them to make these moves? And not only that, but then we’re leaving behind neighborhoods that presumably have some amount of people in them that need help. These are neighborhoods that are probably in most cases victims of a lot of predatory housing practices over the years. These are neighborhoods that we owe something to. Thinking about vouchers as a solution to segregation, they’re not enough. They are a tool in that fight, but they need to come with place-based investments as well. And we also need to recognize that the thing that vouchers do best is really simply to house people. So let’s use them for that, but let’s put in some measures so that we’re not just reproducing the same patterns we see in the housing market.

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Jared Brey is Next City's housing correspondent, based in Philadelphia. He is a former staff writer at Philadelphia magazine and PlanPhilly, and his work has appeared in Columbia Journalism Review, Landscape Architecture Magazine, U.S. News & World Report, Philadelphia Weekly, and other publications.

Follow Jared .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)