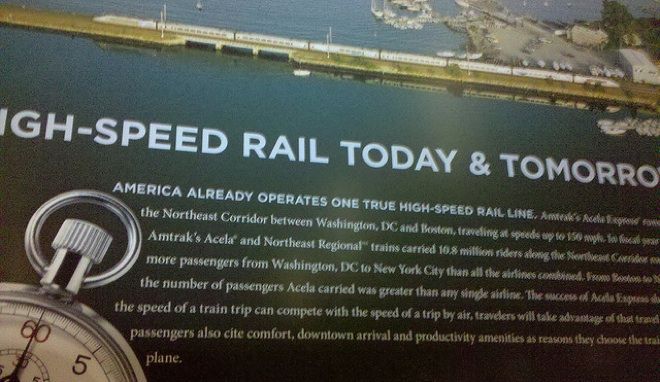

Vogue isn’t a term that conjures up images of vast stretches of infrastructure perfected by years of engineering research and tinkering with delicate designs. There isn’t often a vogue in the transportation world, pragmatism and efficiency reign over aesthetics. High-speed rail is about as close as we’re going to get. However, outside of Acela, Amtrak’s HSR incubator, most U.S. States have rejected funding and most plans haven’t gotten through the nascent stages of design. Economic data has become the preferred angle for general scrutiny: it’s too expensive, it’s not financially efficient, and the ridership numbers are outlandishly optimistic.

I reluctantly agree.

There’s an understandable amount of shock people will have reading such a sentiment on a publication dedicated to moving the urbane forward. I don’t want to think that those arguments are winning angles, but they seem that way right now. The damning economic outlooks from conservative industry spokespeople like Ken Orski and the contested results from projections in Florida and California cast a pale over the initial optimism surrounding domestic rail projects. It’s an exhausting battle that has many outlets calling the fight early in favor of phasing out one of the last frontiers of public works.

I want to alter the doubts, from a doubter’s perspective. There are significant holes in high-speed rail planning here in the U.S. that can’t be filled. The cost, massive to be sure, provides ample anxiety for a debt-weary public. Those realities aren’t static, though. There is ample chance to balance the books through ancillary effects that can be best explained through simple economic geography; I promise, this won’t be painful.

Economic geography, through the eyes of luminaries like Paul Krugman (yes, that Paul Krugman), Masahisa Fujita, and Anthony Venable, is defined by our links between industry and workforce, and for our purposes here, our links between cities. Plainly, urban areas are a series of concentric circles, expanding out into the suburbs, exurbs, and in some cases, our agricultural land. Land prices go down, for a lot of reasons, as you move towards the outer rings. This is why we don’t have 10-acre farms in downtown St. Louis. The city-economy schematic was popularized by J.H. Von Thunen in the 19th century, and while we’ve learned a lot since then the general model still applies on a superficial level: cities, especially cities with well-paying jobs, are expensive to live in.

The significance of the linkage theory for high-speed rail here in the U.S. is actually best exhibited by one of the most successful HSR lines in the world: the Madrid-Barcelona line in Spain. The distance between the two Spanish cities is about equal to that of San Francisco and Los Angeles which is the second-most important link, economically speaking, next to the Boston-Washington corridor where 1 in every 5 Americans live. And while the populations of both the Los Angeles and San Francisco metro areas eclipse that of their Spanish counterparts, the similarities are strong enough to draw comparison.

Looking beyond the superficial, though important, accomplishments of high speed rail in Spain though, reveals a facet of changing preference that I had significant doubts about until I saw the data for myself: the 362-mile ride from Madrid to Barcelona is actually more popular on rail than it is by plane. I had typically hinged my arguments against HSR on the position that it could never dominate modal share —a favorite of the transportation theorist’s lexicon that simply means how many travelers use one form of transportation compared to others— compared to air-travel. I am—happily— wrong. Majority mode share on the Madrid-Barcelona line has eclipsed that of air travel and many business travelers just don’t want to go back to the airport. Does this mean that travel between Boston and New York will soon be majority rail-bound? Believe it or not, it already is! Acela carries more than half of all passengers between the two cities and has a goal of pushing that number closer to complete dominance especially if the current travel time (just north of 3 hours) can be cut significantly through high speed rail (slightly less than 1.5 hours).

The modal share argument encompasses criticisms that politicians and fiscal conservatives have against HSR: the rider projections are too optimistic, price competitiveness is going to be an issue, our geographic and demographic makeup is unique enough that the conclusions would be significantly different when compared to Europe and Japan. The last point is important: American exceptionalism does not limit itself to foreign policy and general ideas regarding personal excellence, opponents of high speed rail have invoked our “purple mountain’s majesty” as a reason why HSR could never work on a wide scale domestically. These are all arguments that have general merit; projecting passenger receipts is a difficult task, akin to toll revenue projections on bridges, which makes for a shaky private investment model.

What this generally means, though, is that high-speed rail needs to be built where density allows for high modal share like the Boston-Washington corridor or the Los Angeles-San Francisco line. The high-density landings for these rail systems also encourage a competitive transportation market between rail and airlines, reducing prices for consumers in the long run. The geographical argument, most compelling because of the historical disparity between this country’s infrastructure development and others that have already built high-speed rail lines, is applicable to the interior of the country where distances between major cities dwarfs those between European and Japanese cities. Coastal high-speed rail negates those arguments; we become more economically amicable to high-speed rail as we move East and West from the core of the country.

Disliking high-speed rail wasn’t a matter of politics for me. My job as a transportation analyst exposed me to some of the more technical and environmental arguments surrounding a new transportation infrastructure, the majority of them positive. The per-passenger rates of emission on HSR are significantly lower than that of air travel, for example. I thought HSR was just too expensive for a country that is dealing with historically low government tax receipts and a faltering private recovery. The economic arguments are there though, and while not applicable for large swaths of the country—the Tampa-Orlando line among them— the Northeast and Western corridors can be run at operating surpluses. The differentiation between terms is important here because a system that runs an operating surplus is making a de facto profit: their income outpaces their non-capital related expenses. HSR is unlikely to be a capital gainer in the short run because of the behemoth initial investment needed to actually build the infrastructure. However, everyone who has spent time riding on the interstate highway system can see a gleaming example of a capital loser that turned into a winner.

I didn’t begin this article with the intention of becoming convinced that high-speed rail needs to be central to this country’s infrastructure future. The moment came in early June; I had come back to California, seeing family and friends and escaping the fledgling New England summer, and as my brother was driving us home on Interstate-5 I looked around and saw how the landscape had been transformed by a great construction project 50 years ago. Concrete dominated what were once orange groves. The precedence for large-scale public works was set when Dwight D. Eisenhower wanted a domestic system that could transport our national security apparatus around the country without depending on aerospace , a sector that would be especially vulnerable in the case of war. High-speed rail takes that dream to its logical evolution: create a system where we link cities so well that the national economy revives uniformly and the rust belt can oxidize completely. Transportation is, in its essence, providing the services of one place for a consumer in another place with distance being the time it takes to provide it. High-speed rail will do more to truncate that time than anything in the last 50 years.

Theodore Brown is a transportation consultant who works with U.S. based Highway and Public Transportation authorities and founder of Radials Blog. The site specializes in all aspects of transportation policy from the development of rickshaw laws in India to the current high-speed rail debate in the United States. Theodore graduated from Boston University in 2010 with a degree in Environmental Policy specializing in transportation studies and has spent time living in Mexico, Thailand, Singapore, and Scotland. Originally from Southern California, he now lives and works in Boston where he simply thinks about the days when he used to live in Southern California. Follow Theodore on Twitter, or get in touch via email.