This piece originally appeared on Crosscut.

With the March 15 launch of a $22.7 million project to make Seattle’s King Street Station less vulnerable to earthquakes, the Washington State Department of Transportation has embarked on the start of a long series of passenger rail upgrades to be underwritten by federal high-speed rail (HSR) outlays. Unanimity does not prevail, however, on how some of the money could be best spent.

Coming more than two years after the first federal HSR awards were announced at a media event headlined by President Obama and Vice President Biden, the King Street event also attested to a peculiarity of the high-speed rail program. Because the funding conduit, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), had never before doled out such a series of grants and most of the grants affected private property — the railroads on whose tracks Amtrak runs — the grants’ processing dragged on and on. Rail advocates nervously wondered if the rightward-shifting political climate would lead Congress to recoup funds already awarded but not contractually committed to states.

As it turned out, no Congressional takebacks occurred, but the HSR program as such has not been funded for the last two federal fiscal years, and chances for its revival look dim. On the other hand, stimulus-funded jobs that Americans thought were already history are just now being filled to improve rail service in Washington state and elsewhere.

The term “high speed,” defined by the FRA as a sustained speed of 110 mph or higher, is meanwhile less heard than it was three years ago, when Obama put $8 billion in high-speed funding into his 2009 stimulus legislation. The discourse has now largely shifted to “higher-speed rail” and “high-performance rail.” Notably, FRA administrator Joseph Szabo used the latter term in his remarks at the March 15 event.

HSR’s political capital lasted long enough to get the Evergreen State quite a pot of money, however — $791.6 million, out of the $10.1 billion awarded from the federal program. Only California and Illinois got bigger slices of the pie. Oregon, Washington’s partner in the Pacific Northwest HSR corridor project, got less than $20 million, after the feds turned down a $1.8-billion proposal from Salem to transform the corridor’s Portland-Eugene segment into a very high-speed route of the sort depicted by artists’ renderings of trains blurring by.

Washington’s millions will finance all or part of 20 major capital investments. They range from a railyard bypass in Vancouver to a new siding in Blaine for customs inspections. They also include eight new locomotives and a new train set.

Here something of a second windfall may materialize because of recent events in Wisconsin, where the state government has refused to fund a long-term maintenance facility for two sets of Talgo trains purchased by the state and similar to those Washington has long used. The decision may force Wisconsin either to store the trains, which are now in testing, at a cost of $739,400 yearly, or to sell them, possibly at a loss. Washington could, in theory, buy them.

Credit: Flickr user SP8254

Ron Pate, rail operations manager at WSDOT’s Rail and Marine Office, noted that the Badger State’s trains would not, as built, meet federal “Buy America” requirements because of the use of foreign components. “We would need waivers from those requirements,” Pate said. “We would certainly entertain [the possibility] if we could get waivers. That would be a major challenge.”

A Wisconsin Department of Transportation spokesman declined to comment on the possibility that the trains could wind up being sold.

The Pacific Northwest corridor, which stretches from Eugene to Vancouver, British Columbia, will in any event soon see what might be termed a surplus of rolling stock, as the Oregon Department of Transportation will be taking delivery of two Talgo sets, but without any plans for an immediate increase in service. The cars will become part of the corridor’s equipment pool — which has proven adequate as things stand. Pate said that WSDOT “might use one of those,” but that discussions with Oregon on a plan for the pool’s future management were still in progress.

The established plan assumes an expansion of service by 2017. To go along with a limited-stop express service, WSDOT is giving active consideration to a possible second-tier service making more frequent stops. “I believe it’s possible,” Pate said. “The whole thing is about getting people on the train and making it available when they need it.”

By year’s end, five major projects will put the federal dollars to work. In addition to King Street’s seismic retrofit, they include work on a key rail link in Tacoma, improvement in the track condition generally between Seattle and Portland, installation of new tracks in Everett to keep freight trains out of the passenger trains’ way, and installation of an advanced signaling system that will streamline movement of freight and passenger traffic up and down the corridor.

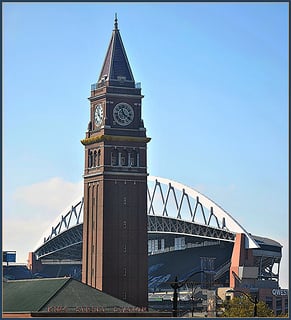

King Street Station in Seattle, due for a retrofit.

Credit: Steve Wilson on Flickr

Taken as a whole, the HSR track projects should reduce travel time by 10 minutes between Portland and Seattle; the newly purchased Talgo trains in Oregon will meanwhile allow for two new Portland-Seattle round-trips by 2017. The time saving assumes that the trains make all intermediate stops, as they do now. Since a stop consumes about five minutes, a Portland-Seattle express calling en route only at Tacoma and Olympia, omitting three other stations, would shave an additional 15 minutes. With the other speed improvements, that could reduce travel time to just over three hours, and likely coax more time-sensitive travelers away from the I-5 slog.

Understandably, mayors in communities the trains serve, or might serve, tend to enthuse over the possibilities. In Lakewood, however, the situation is different. Currently a little-used freight line crosses the town. The federally funded state improvements include an 18-mile reroute of the Seattle-Portland line through the city, however, and locals have been up in arms over the prospect of passenger trains zipping through, without a stop, at speeds approaching 80 mph 12 times a day. In January 2010 the Lakewood City Council unanimously passed a resolution opposing the plan formulated by WSDOT. The reroute is currently undergoing environmental review. Calls to the city seeking an update on the city’s situation were not returned.

The Tacoma suburb has not been the only source of political friction over the program. “Generally we think that high-speed rail is extremely wasteful,” commented Michael Ennis of the Washington Policy Center.

“With the capital improvements, you’re expanding that system, which makes the annual operating subsidy even higher,” he continued, referring to Washington’s corridor. “Taxpayers should not be subsidizing a mode that competes with the private sector, in this case the airlines.”

Lloyd Flem, executive director of the state’s passenger rail advocacy group All Aboard Washington, countered, “Switzerland, arguably the most economically conservative, capitalist industrialized country in the Western world, leads the world in per-capita investment in passenger rail. What do the wealthy, successful Swiss know that the Washington Policy Center obviously doesn’t?”

Washingtonians are in any event getting used to big transportation bills — whatever the transportation mode. Washington State Ferries spent more than a million dollars on each car slot on its recently purchased Kwa-di Tabil class boats, and the new 520 bridge across Lake Washington carries a $4.2 billion bill. The costs and benefits of each mode furnish fodder for debates that can never be entirely resolved. As discussions drag out, however, the price tags often get even more daunting.