Some mayors, like New York’s Bill de Blasio, have trumpeted the often-used notion of a “tale of two cities” to describe the staggering gap between their richest and poorest residents. But income inequality is not equal across the nation’s largest cities. To get a better sense of the specific local impacts of income inequality, it’s helpful to examine the so-called “95/20 ratio.”

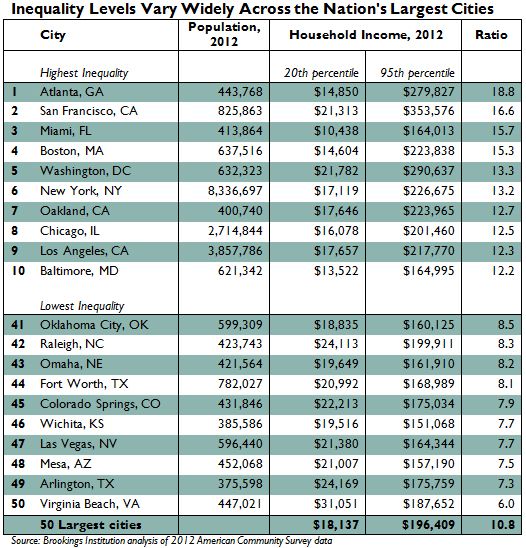

Using that ratio — which “represents the distance between a household that just cracks the top 5 percent by income, and one that just falls into the bottom 20 percent” — a Brookings Institution report released Thursday found that among the 50 largest U.S. cities, inequality was the most severe in Atlanta, followed by San Francisco, Miami and Boston.

In Boston, for instance, a household in the 95th percentile of income distribution earned at least 15 times as much as a household in the 20th percentile. But looking at two cities with similar 95/20 ratios, San Francisco (with a 16.6 ratio) and Miami (with a 15.7 ratio), can paint very different pictures of income inequality.

In San Francisco, where the ongoing debate over tech company employee shuttle buses has thrust the income-gap issue into local and national discussion, high-income earners are considerably more wealthy — in fact, more so than in any other U.S. city. In Miami, there are only pockets of high-income earners amid a large poor population with very low incomes.

The Brookings study, which relied on 2012 Census data, found that major cities with the lowest inequality are generally found in Southern and Western states and are sprawling in nature, like Raleigh, N.C., Oklahoma City and Las Vegas. Others, like Mesa, Ariz., and Arlington, Texas, are large suburbs within larger metropolitan areas.

Upper-end incomes in those lowest-inequality cities run from $150,000 to $200,000 while lower-end incomes range from $19,000 and $24,000.

Brookings points out that while income inequality in the nation’s largest cities worsened between 2007 and 2012, the “trend is neither profound nor uniform.” Between 2007 and 2012, the 95/20 ratio for the 50 largest cities grew from 10.0 to 10.8, with San Francisco seeing the largest increase.

Income inequality also increased in cities where high-income earners became less rich in the five-year period studied, which begins with the start of the recession. Looking at Jacksonville, Fla., Brookings found that rich households in 2012 earned $19,000 less (11 percent) than they did in 2007. But lower-income earners made $8,000 less in the same period, a 31 percent difference.

As the report bluntly puts it, “inequality rose not because the rich got richer while the poor got poorer — but because the rich became somewhat poorer while the poor got much poorer.” That trend was found in many of the cities Brookings studied.

The report will surely give ammunition to mayors who campaigned on closing the gap between rich and poor. In his inaugural address last month, Boston’s new mayor, Marty Walsh, said that his residents should not “tolerate a city divided by privilege and poverty.” But as Boston public radio station WBUR-FM asked, what can mayors actually do to counteract income inequality?

It’s a complex question that stirs many responses. Some, for instance, don’t believe mayors should do anything at all. For them, income inequality is a sign of a city’s economic strength.

“I can’t stress enough how important it is not to view the coexistence of wealth and poverty as something damning about Boston,” Harvard University economist Edward Glaeser told WBUR. “The city should take pride that it has a thriving financial sector, that it has a thriving tech sector, that it has well-paid doctors.”

An examination of the Brookings report by the New York Times noted that “inequality is sharply higher in economically vibrant cities like New York and San Francisco than in less dynamic ones like Columbus, Ohio, and Wichita, Kan.”

The author of the Brookings study, Alan Berube, echoed that notion. He told the Times: “These more equal cities — they’re not home to the sectors driving economic growth, like technology and finance.”

Read the full report here.