Many small U.S. cities, population 200,000 and under, are dealing with the same challenges (from poverty to rising housing costs) seen in New York and San Francisco. Similarly, many are also reaching for inclusive prosperity. How they fare, according to a new report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, matters greatly to the country’s overall well-being.

In “Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities,” authors Torey Hollingsworth and Alison Goebel write that many smaller legacy cities in particular “still have enduring roles in the national economy, and even more of them are important in their state and region. Many serve as economic, cultural, and service anchors for metropolitan areas that are home to millions of people and that produce significant economic outputs.”

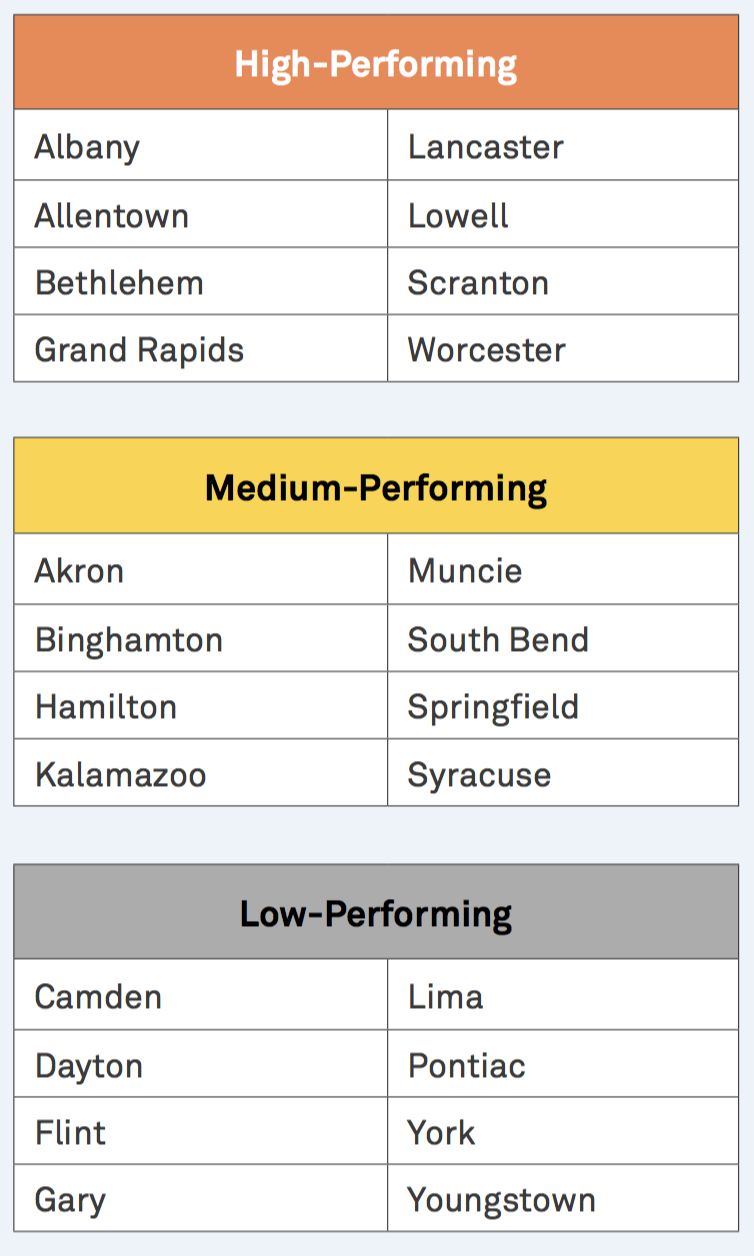

They found that some smaller legacy cities — which they define as places with between 30,000 and 200,000 residents and deep roots in the industrial era — are doing better than others. They rank Albany, Scranton and Grand Rapids as higher-performing. Cities on their low-performing list include Flint and Youngstown. Muncie, in Indiana, and Syracuse are among the medium performers.

(From the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy's “Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities”)

The report delves beneath the sound bites about high Midwest poverty rates, manufacturing’s steep decline and the 2016 presidential election to reveal a detailed picture of some of the country’s most left-behind economies — and the actions necessary for reversing that trend.

Most of the 24 cities Hollingsworth and Goebel studied are in the Midwest and the Northeast. They collected U.S. Census and American Community Survey data on populations, unemployment and housing vacancy, among other factors. They calculated the percentage change in selected categories from 2000 to 2015, and further broke that 15-year range into two subsets, 2000 to 2009 and 2009 to 2015, to gauge the impact of the Great Recession.“For the most part, higher-performing cities were strong across economic, demographic, and housing measures,” the authors write. “For example, Lowell had the highest median household income, the lowest rate of long-term housing vacancy, and the largest share of foreign-born residents in 2015, with significant strength in all three categories.” Meanwhile, lower-performing cities did poorly on those indicators. Flint, for example, “had the highest unemployment rate, the lowest median home values, and the second-smallest share of residents with a college degree in 2015.”

The researchers point out that many of those factors are interdependent. One example: “Professionals and immigrants are less likely to move to cities with few jobs and troubled housing markets.” Beyond that, they note that all but four of the 24 cities were home to at least one Fortune 500 headquarters at some point between 1960 and 2015. Today, however, only half of the cities can still make that claim. The disappearance of that industry is perhaps due to (and perhaps the cause of) the disappearance of smaller, non-hub airports, which may “compound the difficulty of attracting or retaining major corporate headquarters.” Civic and family foundations, which can help guide and support struggling city institutions, also aren’t as common in these smaller legacy cities.

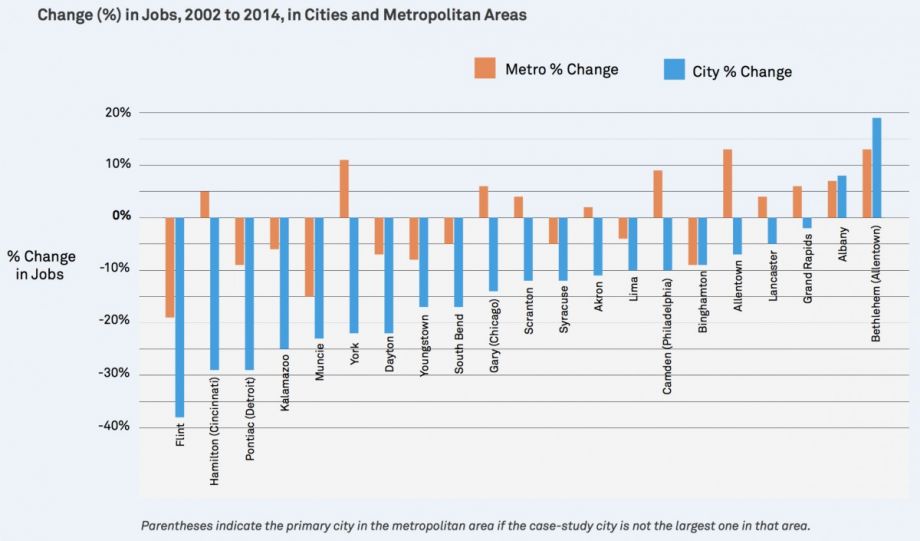

Another trend that emerges (“perhaps the most striking,” according to the authors) is the decline of jobs within city limits. In some cases those jobs just vanished, but in others, they simply moved to the suburbs.

(From the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy's “Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities”)

From the report:

Nearly all cities in the study lost thousands of jobs, representing anywhere between 2 and nearly 40 percent of employment opportunities. Only Albany and Bethlehem saw an increase in the number of jobs in town. For the other 22 cities, the last 15 years meant a significant contraction in local employment. On average, they lost about 17 percent of jobs within their boundaries. Dayton — the city with the greatest drop in job numbers — went from nearly 110,000 in 2002 to just under 86,000 in 2014. Flint which had the greatest percentage decline, went from 62,700 jobs in 2002 to 39,200 in 2014 — a loss of 37.5 percent.

In some cases, the jobs that used to make legacy-city downtowns and industrial parks the economic centers of their region have simply moved to the suburbs. In about half of the cities that lost local jobs, the corresponding metropolitan area saw jobs grow over the same time frame.

Notably, another recently released report, examining Detroit, looked at the same type of jobs shift in that metro and, as Next City writer Oscar Perry Abello reported, “An estimated 158,000 commuters come into the city for work, 59 percent of whom earn more than $40,000 a year. Meanwhile, an estimated 112,000 Detroiters leave the city for work, 36 percent of whom earn $15,000 a year or less.”

Not surprisingly, smaller legacies, Hollingsworth and Goebel found, have been hit with higher poverty rates than the country as a whole.

(From the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy's “Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities”)

All is not bleak. These smaller legacy cities tend to have dense, walkable downtowns. Many were set up with intentional grids that prioritized public transportation. Unlike the cities of the West Coast and Southwest, they’re not completely built around cars, and so they have potential to grow in population with fewer emissions and more public space equity. Young professionals, though scarce, are moving to a number of them in slightly greater numbers than the country as a whole (perhaps due to their abundant and relatively cheap housing stock).

(From the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy's “Revitalizing America’s Smaller Legacy Cities”)

The authors of the Lincoln Institute report offer a number of guideposts for city growth, with examples. One strategy: leveraging state policies, like the Ohio law authorizing counties to create local land banks. To expand opportunities for low-income workers, they say, look to Syracuse, New York, where the regional chamber of commerce recently tied a redevelopment project to higher-paying jobs.

“Though all of these cities are still experiencing significant challenges, some are finding ways to reorient their economies and land use for the 21st century,” they write. “As people, capital, and corporations continue to concentrate in fewer places, small and midsize legacy cities must creatively reimagine their place in the world. The strongest of these cities recognize that they cannot recreate the past.”

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)