Bernie Sanders may have bankrolled his 2016 presidential campaign with an unprecedented number of small donations averaging $27 each, but in the end, the election — including the cabinet President-elect Donald Trump is now assembling —has been a coup for the moneyed and influential. Many urban voters where majorities turned out for Hillary Clinton are doubting the entire electoral process. Still, cities aren’t giving up on getting out the vote in the future — or in engaging citizens in the political process.

One city, though, is ending the year with a vote for local campaign finance reform, and another will launch its own reform starting in 2017. Earlier this month, Portland’s city council approved an initiative that will match residents’ small campaign contributions 6 to 1, transforming a $10 donation into a $70 one, and $50 into $350. In 2017, Seattle will implement the country’s first experiment with “democracy vouchers.” Every resident 18 years or older will receive four vouchers worth $25 each they can give to any local candidate of their choice, provided those candidates opt in to strict limits on spending and receiving private donations.

If it works as supporters intend, residents won’t need to spend a dime of their own money to support candidates, people without wealthy donor pools or deep pockets of their own will be able to run on a more even playing field, and all candidates will be encouraged to spend more time talking to the voters than on soliciting big donations.

“We’ve seen what happens with our elected officials and the special interests that are able to buy and sell our elected officials. We’ve talked to elected officials who literally say they are out spending most of their time raising money, not talking to their constituents,” says Alissa Haslam, executive director of Win/Win Network, a Seattle coalition of progressive organizations that organized around the Honest Elections initiative. “We’re hoping it will encourage politicians to go speak to people at their door step, because every voter is now a potential donor.”

The initiative, adopted by popular vote in 2015, is funded by a property tax expected to raise around $6 million per year. Participating candidates can raise no more than $250 each from individual donors, $350 including democracy vouchers. Candidates who don’t participate can accept up to $500 from individual donors. The initiative also includes provisions banning contributions from contractors who do more than $250,000 worth of business with the city, or groups that spend more than $5,000 a year lobbying the city.

The goal, says Haslam, is not just to limit big money in politics but to “elevate community voice.” Elected officials make policy, “and if they’re not in touch with what’s going on with community, and there are special interests that are trying to influence them, it creates this disillusionment you see in voters right now.” At the same time, Win/Win hopes the vouchers will create funding pools for community organizers, activists and other grassroots candidates to run successful campaigns.

Portland’s public campaign finance system, which will come into effect in 2020, has many of the same aims. In Portland, as in Seattle, big donors have an outsized influence on local elections. White, wealthy, male donors living on the waterfront dominate Seattle’s campaign contributions, while in Portland, just 400 wealthy donors played a disproportionate role financing the 2016 mayoral race, according to the Sightline Institute.

“To run a successful campaign you have one list that you call that’s like 400 people that you’re asking for big checks from, and then you separately have your town hall meetings where you’re reaching out to voters and asking them to vote for you,” says Kristin Eberhard, senior researcher at the Sightline Institute. “The idea is that candidates under this program will combine those two activities into one.”

Portland’s program is based on one in New York. Unlike in Seattle’s untested voucher program, Portland residents will need to give some of their own money in order to trigger the public funding. Contributions up to $50 will be matched by the city. In return, participating candidates must agree not to accept contributions from individuals of more than $250, and to reject contributions from organizations altogether, including PACs, parties and unions. They also agree to caps on overall fundraising and their total use of public funds. Outside of this program, Oregon imposes no contribution limits.

“The hope is that will change the way that people in Portland relate to politics, that they will see people who are more like them, coming to talk to them, reaching them to become civically engaged, and then hopefully coming to office and keeping regular people in mind rather than keeping in mind those 400 people who have unlimited bucks available,” says Eberhard.

There is evidence that New York City’s similar small donation matching program has achieved some of those results. According to an analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice, New York state assembly candidates — who are not eligible for the public funds — raised small donor gifts mostly from the same 30 percent of neighborhoods from which they received large campaign contributions. New York city council candidates, on the other hand, raised small-dollar contributions from almost 90 percent of city neighborhoods. As in Portland, participating candidates need to raise a certain amount via small donations to even qualify for the public funding, guaranteeing that voters’ voices count from the start.

The Brennan Center also found evidence of less tangible effects. A list of 2009 donors to council candidates revealed not only lawyers and doctors, but also artists, barbers, cab drivers, carpenters, nurses and police officers. And the Center estimates that campaigns have in fact altered their outreach efforts to spend more time in the living rooms of ordinary voters.

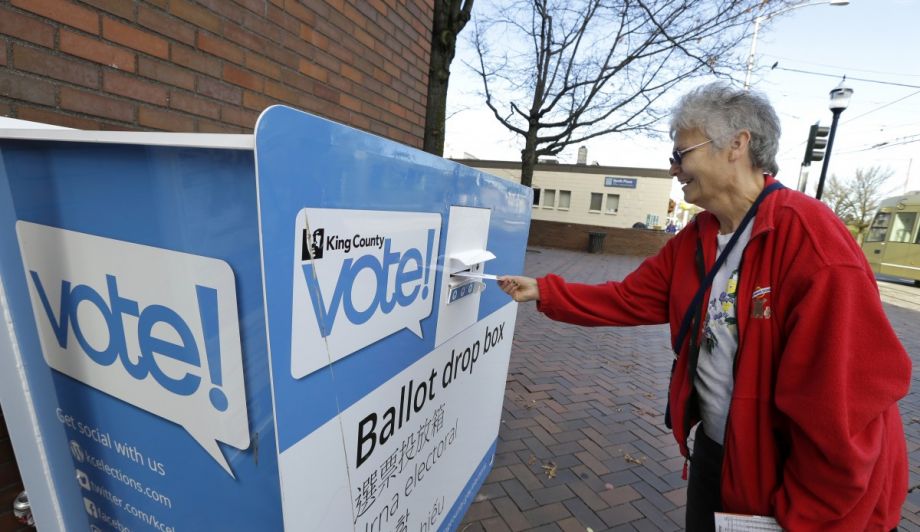

While Portland’s program won’t go into effect until 2020, Seattle’s vouchers will be available for three races in the coming year: two at-large city council members, and the city attorney. After the initiative passed last year, Win/Win worked with the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission to ensure the policy is rolled out with integrity. Thanks to Washington State’s robust public disclosure laws, they’ll be tracking who is using the vouchers, where they live, and when they use them, in order to tweak the policy for coming years.

Already, Haslam imagines the timing of the vouchers will need to change. This year, they’ll be mailed out in January, long before most candidates will even have announced their run. Win/Win and coalition partners will be launching a campaign as vouchers mail to educate people on how to use them (and not to throw them away). To use them, voters can give them directly to a candidate or mail them to the Ethics and Elections Commission.

There will also be opportunity to tweak the threshold for qualifying contributions and the rules around outside expenditures. In both cities, if participating candidates are being vastly outspent by candidates not taking the public funding, there’s an escape clause that will allow them to go out and raise larger contributions.

Because the exception to all of this, of course, is a so-called “Bloomberg candidate” — a candidate with enough personal wealth to bankroll his campaign without public funding and without needing to hit up big donors who are themselves subject to contribution limits.

Still, Mark Green, who ran against Bloomberg in 2001, told Brennan Center researchers, “it is irrational to argue against a system that enables a diverse group of people to run competitive campaigns because a wealthy candidate can occasionally outspend a participating candidate.” He lost, but had a better leg to stand on than if the public funding didn’t exist.

The Seattle Times did not endorse the initiative when it was on the ballot in 2015, citing among other concerns the loophole that allows candidates to increase their fundraising if they’re being outspent. The paper also took issue with the fact that the $6 million property tax fund would only cover 47,000 residents cashing in their vouchers. Haslam says that’s no reason not to try.

“The reality is that not everyone will use their vouchers. We know that. Not everyone votes,” she says. “[But] we’re not making progress on a lot of areas by not doing anything.”

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)