What if you were asked to live on a bridge? Would you ponder the question for a moment or refuse without hesitation? Architecture has become a seemingly limitless field, propelled ever further into our imagined future by new technology and new ways of building. Unfortunately bridges remain, at best, in the rearview. Even the most magnificent bridges in the world rarely join the ranks of the Notre-Dame Cathedral, The Guggenheim Museum, or Fallingwater in conversations about masterpieces of the built environment. For many, bridges do not even represent architecture. Why is this so? Is it the aesthetics, the functions, the spaces or the structure that define architecture? Or is it something deeper, more profound than just a list of attributes?

Do you recall the first time you crossed a bridge? Probably not. Bridges have lost their symbolism as agents of connectivity within and between cities. Yes, they do connect points but why do they connect them? For hundreds of years during the Middle Ages some bridges were more than linear conduits; they were connections within the city, part of the urban fabric. What happened to the bridges that gave people such an experience as the inhabitable bridge? A bridge that gave people more than point A and point B but a path connecting these two points, a path that was not uniform and dull, but a path that gave people choices and experiences.

A living bridge, or inhabitable bridge, is a typology long forgotten by the masses. In simple terms it is a bridge that one can live, work and play on or within. Living bridges can range from parks and museums, to apartments and hospitals, their only limit being people, namely those who design and create them and those who allow them to be created. Unlike standard issue bridges that transport users from one side to the other, the living bridge creates a destination and network of connectivity within itself. Inhabitable bridges offer a new tool for cities, creating a destination in the interstitial space that typical utilitarian bridges occupy, space that we by and large treat as uninhabitable. A true living bridge merges both the architecture and the bridge, creating a hybrid. The Ponte Vecchio in Florence and the Ponte Rialto in Venice are two very successful inhabitable bridges that were built during the Middle Ages and are still in use.

Ponte Vecchio, Florence, Italy | Rick Payette

Though appropriate for many settings, the living bridge truly reaches its potential in urban areas, creating a segue between two points of a city, a continuation of the urban fabric. The French term “pont urbanisé”, translated to English as “urbanized bridge”, is a fitting name for a bridge that is seamlessly integrated with the city itself. While a living bridge can exist outside of an urban context, an urbanized bridge depends upon the urban fabric of a city and its unique programming and zoning. Those who live, work and play on the bridge become more than just users, they become part of the bridge, creating a living, breathing connection between modern infrastructure and the city.

Although we can still see some examples of these bridges, they have, for the most part, been destroyed. As society began to grow and progress technologically, inhabitable bridges were slowly phased out. The bridges came to be seen as nuisances to the large ships critical to European commerce and overbuilt, crowded eyesores teeming with buildings and people that blocked views and air circulation. Learning from their failures and their success, a new breed of inhabitable bridges can be designed for the twenty-first century. Bridges of today are appreciated by and large for the feets of modern engineering that allow us to move people and goods across longer and longer expanses suspended higher and higher in the air. However, bridges might further endear themselves to society if they were built to support human scale functionality in addition to traditional transport functions. In becoming destinations, urban bridges could create revenue for the city through commerce and perhaps even pay for itself. One can imagine an urban bridge becoming self-sustaining if“bridge dwellers”were taxed live and do business on the bridge.

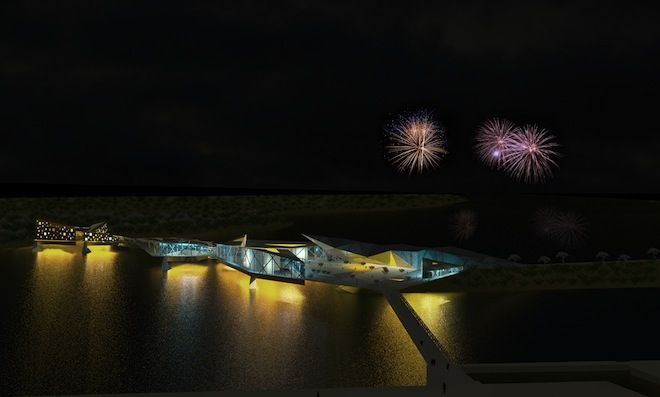

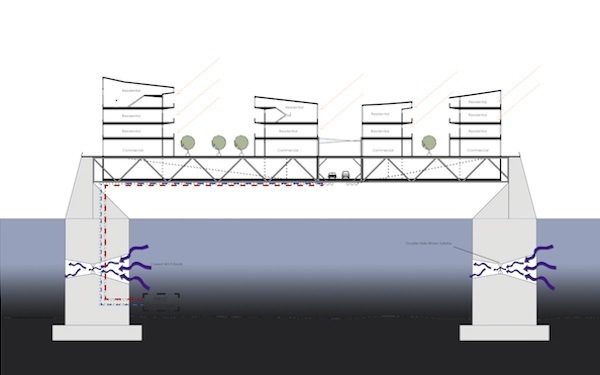

In 2011 I designed an urbanized bridge for Montréal, Québec, which would reconnect The Old Port of Montréal and the home of the World Exposition of 1967, Sainte-Hélène Island. There is a striking loss of connection between these two points, especially for pedestrians. An urbanized bridge was the best choice to create connectivity for several reasons, one of them being Montréal’s need for more housing in this area. Although the initial cost of an urbanized bridge would be substantially more than a standard bridge, it would in the end pay for itself and create profit. The bridge was designed to house commercial and retail space, residential and mixed-use housing, and a museum to honor the World Exposition of 1967 which forever changed the face of Montréal . The piers of this bridge also revealed a new idea by housing water turbines within their structure to capture the power of the river and use it to power the various functions of the bridge. This was a new type of inhabitable bridge as it was inspired by city streets, specifically the choices they give us. Instead of having one straight path telling users where to go, a variety of paths were included in the design to mimic the cities we live in.

Schematic of a new inhabitable bridge for the city of Montreal that would relink the Old Port, Sainte-Helene Island and Cite du Havre | Maxim Nasab

In July 2011 the idea for this urbanized bridge was published in two different newspapers in Montréal: Journal Métro and The Gazette. The Journal Métro being directed to the younger French demographic and The Gazette which is directed towards the older English demographic of Montréal. When the idea was presented, it allowed for a new discussion to begin. Feedback was mostly positive, with the occasional concern of cost and noise.

The inhabitable bridge was a logical and important part of the Middle Ages all the way to the early nineteenth century. Unfortunately with the arrival of the industrial revolution the living bridge died and only the ideas remained. Many ideas appeared even after the destruction of so many bridges, ideas from architects like Zaha Hadid, Yona Friedman, Zvi Hecker, Steven Holl and even Frank Lloyd Wright. However, ideas need help and sponsors, and unfortunately during the twentieth century the sponsors were not present and another century went by without any new inhabitable bridges. Though the twentieth century was a lull time for living bridges, all these ideas were waiting so impatiently to spark a flame in the next generation of architects who would build and design the next set of living bridges like the Zaragoza Pavilion by Zaha Hadid and Golden Gates City by BRT Architekten. The urbanized bridge is the future of our cities. These rediscovered structures hold the potential to create density, infrastructure and revenue for the cities they belong to. So the question is not why should inhabitable bridges be built, but rather “why not?”