There is a movement in many American cities to stabilize the property tax base, as the revenues it produces are critical to adequate city services. As Chicagoans head to the polls to pick their next mayor, there is heightened attention on the pressing need to shore up the city’s tax base and its property values. Meanwhile Baltimore is taking purposeful steps to fight property vacancies by preventing them from happening in the first place. In both cities, local decision-makers are focused on neighborhoods that have received little attention: middle neighborhoods. Chicago and Baltimore are just two examples of cities around the United States that are elevating the importance of the middle class and their communities into the national conversation. In a country increasingly defined by the extreme divergence between the most wealthy individuals and everyone else, the devastating effects of the disappearing middle are threatening the livelihoods of all.

In many ways, the publication of “On the Edge: America’s Middle Neighborhoods” in 2016 provided a starting point for understanding what’s happening to middle neighborhoods throughout the country and importantly, what steps can be taken to ensure that these places remain home to the vital “center” of so many cities across America.

Following publication of “On the Edge,” a series of convenings, most recently in Cleveland, is bringing together city officials, community development practitioners and researchers into a community of practice in support of middle neighborhoods dedicated to finding portable solutions to ensure the stability of middle neighborhoods in the years and generations to come. Key themes emerging from the convening in Cleveland reaffirm many of the observations Reinvestment Fund has made through our work in cities throughout the country.

Focusing on middle neighborhoods is not wholly new. Reinvestment Fund’s efforts in these neighborhoods date back over 15 years when former Philadelphia Mayor John Street launched his $295 million Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI). Street dubbed middle neighborhoods the city’s “key battleground” areas; lose them and Philadelphia’s long-term prospects decline. Although many observers and commenters focused on NTI’s emphasis on demolition of vacant housing units, the very first principle in Street’s rollout of NTI was “Preserve Healthy Neighborhoods.” These were central to NTI’s “build from strength” approach to neighborhood stabilization and revitalization.

But what characteristics define a healthy neighborhood? Where are they located and what threatens their future?

Over the past five years, Reinvestment Fund has conducted comprehensive real estate market studies in a diverse range of cities — from Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore, to Jacksonville, New Orleans, and Houston, to Dallas, Kansas City, and St. Louis — using an analytic approach developed for NTI. In all these places, the emergent challenges facing middle neighborhoods tend to be associated with restricted access to conventional mortgage lending, increasing investor activity, fraying commercial corridors, and displacement pressure from “above” in instances where the middle neighborhoods are located near a re-emergent inner core, but more frequently from the “push” of neighborhood decline and softening demand. These factors collectively threaten the ongoing stability of these communities.

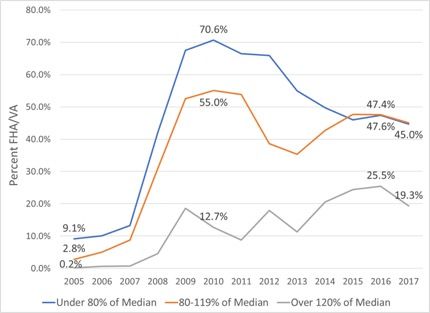

In the mortgage market, middle neighborhoods face two related phenomena that portend uncertain times ahead for many of these places. On the one hand, conventional mortgage lending has become increasingly tight in middle neighborhoods in the decade since the mortgage market collapse of 2008. In cities throughout the country, Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured mortgages are becoming the de facto mortgage product of choice for many middle-income borrowers in middle neighborhoods. The chart below presents FHA/Veterans Affairs market share in Philadelphia from 2005 to 2017 across neighborhoods at different income levels.

Percent of Philadelphia home purchase mortgages with FHA/VA insurance, 2005-2017 by census tract ratio of income to area median (Source: HMDA)

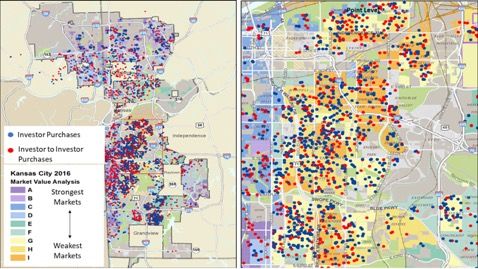

On the other hand, cash transactions and home sales to investors have begun to assume an increasing share of middle neighborhood real estate activity. Through this process, historically owner-occupied neighborhoods may be transitioning into majority rental neighborhoods in cities throughout the country. What this means for the long-term health and vitality of these places remains to be seen, but the potential loss in owner equity cannot be ignored. The maps below show the location of investor purchases from owners (blue dots) and investor to investor purchases (red dots) in Kansas City, Missouri, from 2014 to 2016.

Investor purchase activity in Kansas City, Missouri, 2014-2016 (Source: Kansas City Market Value Analysis)

Another ongoing flashpoint for city officials and practitioners working in middle neighborhoods is the displacement risk faced by individuals and families in these communities. In many middle neighborhoods, residents face displacement pressure associated with neighborhood decline. Many middle neighborhood residents in areas with aging housing stock, and where people may have not fully recovered from the mortgage market collapse, are increasingly faced with a decision to hang on to their homes where deferred maintenance is slipping into blight, distressed sales remaining vacant, owners selling to investors who are renting their properties, and public safety becoming a major concern (when it was previously an afterthought). Many of the residents in these communities do not qualify for programs funded with public resources, yet they lack the financial wherewithal (or incentive) to maintain their homes or remain in their communities.

On the other hand, in a few (but highly publicized) places, this pressure is felt from above. In rapidly appreciating markets, longtime residents, particularly those on fixed incomes, can find it difficult to keep up with rising rents and property taxes to enjoy the increased amenities that come with robust development in these areas. In addition, there are increasing reports of strategic displacement, i.e. eviction of long-term renters by developers seeking to extract higher rents in new or redeveloped properties in these communities.

Finally, some middle neighborhoods face challenges associated with fraying commercial corridors that, in the past, were not only centers of neighborhood commerce, but also supported social life. In city after city, it’s clear to see the interdependence of the health and vitality of commercial corridors with the surrounding neighborhoods that represent their primary patron base. Many of the small business owners who occupy these corridors (oftentimes small retail and service businesses) face a set of complex macroeconomic forces (i.e., historic and emerging competition from big-box stores, chains, online shopping, home delivery services, and so on) that exert considerable commercial pressure on their sustainability. The map below shows the turnover of businesses along the Ogontz Ave. commercial corridor in a middle neighborhood in Philadelphia, where the number of establishments declined from 173 in 2008 to 157 in 2013 (pink circles are business closures; blue squares are business openings).

Business turnover along Ogontz Avenue, Philadelphia, 2008-2013 (Source: Philadelphia Market Value Analysis; National Establishments Time Series)

When local residents are no longer able, or willing, to patronize their neighborhood establishments, the ability of these operators to carry on erodes. In these situations, there is a very real risk that a neighborhood falls into a vicious cycle. As neighborhoods fail to thrive, that adversely impacts the corridors. And as those decline, they damage the appeal of the community as well as the social networks the businesses help foster.

That’s because these commercial corridors are not just economic engines in middle neighborhoods. They are also where people see their neighbors, share their experiences over a meal and discuss solutions to life’s everyday challenges. In short, they are a unifying element of their neighborhoods that meets both material and social needs of local residents. In many middle neighborhoods throughout the country, the fate of the residential housing market is, and will continue to be, ineluctably tied to the fate of the commercial strips that bring, and keep, these places together.

In the face of these mutually reinforcing challenges, the public and private sectors are innovating approaches to support their middle neighborhoods. Persistent demand for affordable housing has led to private developers and financiers (predominantly community development financial institutions, or CDFIs, and other nontraditional lenders) to begin building out approaches to market affordable housing development in the single and multifamily sectors. Market affordable housing looks different in different markets, but is generally characterized as housing created with no, or very little, subsidy that remains affordable for residents and profitable for developers and financiers. In addition, a number of cities have created, or expanded, home rehab programs with income limits sufficiently above the median income in the region so residents of middle neighborhoods can access these programs for resources to support home improvement and maintenance. And an increasing number of cities have adopted new policies to provide renters with additional protections from forced displacement from their homes.

Understanding how these countervailing forces will shape the landscape of American cities over the middle half of the 21st century is critically important — and not just for those who work in community and economic development, but urgently for the individuals, families and small businesses who call middle neighborhoods home. Recent attention in Detroit and Chicago has centered on the disproportionate impacts middle neighborhood displacement has had on African-American households and intergenerational wealth. Those working on middle neighborhoods will meet in Chicago in November for their third national working group meeting. Among other topics, this convening will address a prevailing challenge of this young middle neighborhood movement: How do cities prioritize anything other than the poorest places at a time when community development resources remain scarce and are increasingly under threat? Policymakers and practitioners seeking to be strategic and purposeful in their efforts to support their communities would do well to keep Ben Franklin’s axiom close at hand: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

This op-ed is part of Next City’s Middle Neighborhoods series, supported by a grant from The American Assembly. Follow our coverage as we dig into the solutions and success stories that animate the conversation today.

Michael Norton serves as chief policy analyst at Reinvestment Fund, where he supports all research related to Reinvestment Fund’s organizational goals and mission. In this role, Dr. Norton works closely with a range of partners, including small nonprofit organizations, local and national philanthropies, private companies, colleges and universities, school districts, and federal, state, and city governments and agencies. His work leverages nearly a decade of experience as a researcher and project director to develop data-driven solutions — solutions that meet the unique needs of Reinvestment Fund and our key stakeholders in the public and private sectors. Dr. Norton completed his doctoral studies in the sociology department at Temple University, where his research examined the relationship between secondary mortgage market activity and neighborhood change in the Philadelphia region at the turn of the 21st century.

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)