Donetsk in normal times was a bustling metropolis of a million people, the largest city in industrial eastern Ukraine, home to coal mines and steel mills. But for the last year, civil war has engulfed the region, despite ceasefire agreements and ongoing diplomacy.

The city serves as the capital of the self-styled “Donetsk People’s Republic” of pro-Russian separatists against the Ukrainian government in Kiev, and the front lines are only a few miles from downtown. Fierce fighting at the airport and surrounding regions has persisted for months.

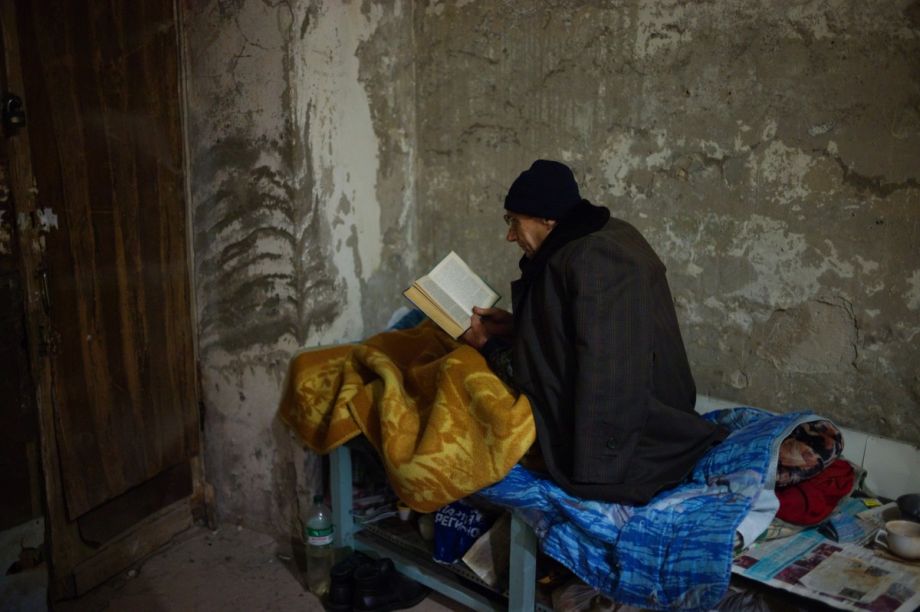

Without air or rail connections anymore, Donetsk has become a surreal alternate universe of a city. The power is on, hot water flows from the taps and the garbage gets picked up, but all banks and post offices are closed. There’s a nightly curfew, and the streets mostly empty except for soldiers and armed men. Humanitarian aid trickles in from both Russia and Ukraine, and long lines form whenever there is a distribution. Thousands of people, especially the elderly and vulnerable, live in local community center or school basements converted into makeshift bomb shelters, either because their homes are too close to the front or were destroyed.

The war has ratcheted up in recent weeks with a separatist offensive and increased shelling killing civilians on both sides. President Barack Obama is publicly debating whether or not the United States should provide Ukraine with weapons as well as non-lethal assistance, and Donetsk’s isolation has increased with some Ukrainian mobile phone companies cutting off service because they cannot access or maintain their cell towers and equipment there.

One architectural casualty has been the Donetsk Regional History Museum, badly damaged by bombing last summer and still struggling to recover. An entire wing of the structure collapsed, and explosions shattered every piece of glass. Makeshift plywood and plastic sheeting covers the window frames of the surviving parts of the building.

The Donetsk Regional History Museum was damaged by shelling in August.

Nikolai Sklyalov, 53, the senior science curator, gave me a tour in late December. I found him in the dimly lit entrance next to two large stuffed moose that were saved from the debris. He explained that they have received no help other than from local volunteers: “We are repairing everything by ourselves. No windows, no doors. Our last regular salary was in June, and we received some emergency money in September, but that’s been it. We had 160 employees before, now we are down to 60.”

Nikolai Sklyalov, 53, is the senior science curator at Donetsk Regional History Museum. He’s pictured here with an architectural model of an Orthodox church.

Luckily, the bombardment came at night when the museum was already closed for the day so nobody was hurt. According to Sklyakov, the first impacts were near misses, nicking some of the statuary in the garden. Then the clock stopped at 8:43 p.m. with direct hits. He didn’t want to say whether he thought the museum was targeted, or if it was a mistake.

He admitted that there had been a “little bit of looting” afterward and that they don’t have an accurate inventory of what’s left. “We planned to reopen some halls before the New Year but now we’re delayed. We have to check against our register; some exhibits are under the ruins. Nor can we reach the archaeology collection in the basement.”

The halls have been largely cleaned up, with only the largest items remaining, including a woolly mammoth wrapped up in protective blanketing, its tusks protruding, composer Sergei Prokofiev’s grand piano, and an architectural model of an Orthodox church. The newest acquisitions lie on the floor of the main corridor: shards of twisted metal, the remnants of rockets and bombs collected from current battlefields.

Two taxidermied moose that were salvaged from Donetsk Regional History Museum’s destroyed natural history exhibit.

The collapsed wing formerly housed the museum’s natural history exhibit. Showing me the wreckage, Sklyakov said, “Here was the music of the forest: deer, swans and big fish. Children loved it.”

Like municipal museums the world over, Donetsk’s was modest in scope and mission, with students on school trips possibly being the largest audience. The 150,000 items in the collection were largely mundane, focusing on ephemera and flora and fauna.

If that educational mission is core to building cultural identity, Ukraine’s civil war is a stark example of how that falls apart, with the leadership in Kiev and western Ukraine identifying with the cosmopolitan ideals of the European Union, and militants in Donetsk and the Donbass region aligning more with Putin’s Russia. In a city at war under the uncertain flag of a breakaway republic, the fate of a local museum may not rank high on anybody’s list of priorities.“While we’re here, we’ll survive,” the curator concluded, “but we will not be able to reopen on our own. We need financial and moral support.”

Alan Chin was born and raised in New York City’s Chinatown. Since 1996, he has worked in China, the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq and Central Asia. Domestically, Alan has followed the historic trail of the Civil Rights movement, documented the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and covered the 2008 presidential campaign. He is a contributing photographer to Newsweek, the New York Times and BagNews, an editor and photographer at Newsmotion and a photographer at Facing Change: Documenting America (FCDA). Alan’s work is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.