In 2015, residents of the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood between 5th and 9th streets in South Philly gathered with Mural Arts Philadelphia and the nonprofit CohStra to discuss social and environmental justice strategies, and ways to make foundational changes in the community. Trash, said the residents, was their number one problem.

So another initiative was born that day. The group called it Trash Academy, emphasizing the idea that this project would be about “learning” and “testing,” in order to mobilize residents to take the overwhelming and chronic garbage problem into their own hands.

The program has worked continually to revitalize some of most littered areas of the city, namely Mifflin Square Park area and Strawberry Mansion, as well as other parts of North, West and South Philly, through education, workshops, art, activism and grassroots solutions that center the communities’ needs and voices at the top. Trash Academy has mobilized a team of about 30 members and partnered with the City of Philadelphia Streets Department, Clean Water Action, LOMO Environmental Committee, Mural Arts Art Education Department, Philadelphia More Beautiful Committee, South Philadelphia High School Environmental Science Class, and Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet.

“Trash runs deep,” says Paige Scott-Cooper, Trash Academy leader and activist. “It’s not just impacting our environment.”

Trash Academy students in 2019 (Photo by Tieshka Smith, courtesy Trash Academy)

Trash intersects with environmental justice and systemic injustices in many ways, she says. In Philadelphia, the highest concentration of litter is found in low-income communities and can be directly linked to environmental racism and redlining, she adds.

“We have taken the redlining map and laid it over the litter index,” says Hersh. “It’s completely connected.”

Outside contractors also come to these areas to dump, she says. And longstanding disinvestment is the leading cause of the pileup of filth in these areas. It’s not a circular economy—it’s an economy of endless use, she says.

“Part of what we do is make the connection between extraction, production, consumption and disposal,” says Hersh. “Trash is the symptom,” she adds. “We have to have a radical re-thinking of consumption.”

The project employs creative methods to get residents involved in managing their neighborhoods’ trash. One project is their “Plastic-Bag Campaign” collaboration with Clean Water Action and the city’s Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet, to get plastic bag trash and litter off their streets through advocacy and reusable bag distribution. The Trashmobile is a mobile unit operated by high-school students that travels to street fairs and community meetings to educate people on trash as well as ask them how trash affects their lives and neighborhoods. Murals, educational posters and even evocative art on the city’s Big Belly solar trash compactors are a few of the many ways Trash Academy has engaged with and invigorated the city.

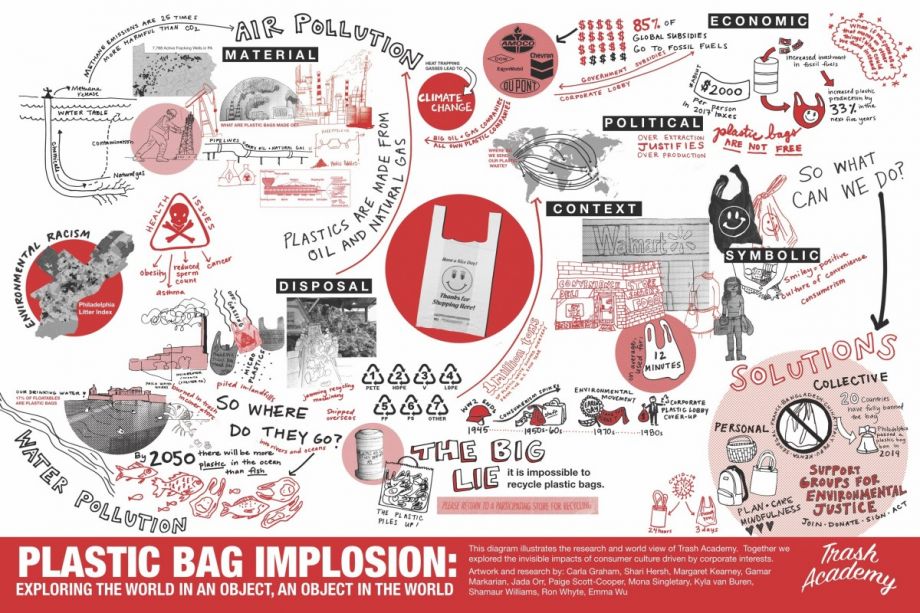

The Academy also uses something called the “implosion method” as an educational tool. It’s a concept started by Donna Haraway, American Professor Emerita in the History of Consciousness department and Feminist Studies department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, that examines “how the world is in an object and how an object is in the world,” says Hersh.

The point is to look at all the different dimensions of an object, and break it down, says Scott-Cooper. She gives the example of a bottle of Arizona tea. “Imploding” the bottle would require an examination of its economic, material, political and historical dimensions, along with its actual organic makeup.

“It helps you understand more about the object,” she says. “Where it comes from, how it’s made.”

And subsequently, the objects’ influence, both locally and globally.

(“Implosion” courtesy Trash Academy)

“We live in a society where we’re disconnected from the impacts,” says Hersh. “Implosion is a super exciting way to do a teach-in.”

The implosions are member-led, and use art and illustrative diagrams to provide interactive experiences for participants.

The implosions, which have taken the form of virtual webinars due to the coronavirus, have upcoming sessions including pandemic-pertinent Charmin toilet paper and the plastic bag.

The pandemic has had other impacts on the Academy. They lost some members, and all participants have endured some form of health, financial and technological misfortune and strain, she says.

“There is a digital divide,” says Hersh. “It’s something we struggle with, because we typically would be going into neighborhoods.”

More than anything, COVID-19 has highlighted racialized capitalism, she says. The intersections between frontline workers, and the pandemic, and capitalism, have risen to the top of our collective consciousness, she adds.

It’s the idea of disposability, she says. The more “disposable” a community seems, the more trash and pollution they suffer from. She points out that research has shown that communities of color are more likely to have an incinerator near their homes.

“Trash is emblematic of how we treat people,” she says. “It’s both a metaphor and a fact.”

This story is a part of our Broke in Philly mini-series, the Hidden Environmental Costs of COVID-19, a partnership between Green Philly and Next City. Broke in Philly is a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push toward economic justice. Next City is one of more than 20 news organizations in the collective. Follow us on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.

Claire Marie Porter was Next City’s INN/Columbia Journalism School intern for Fall 2020. She is a Pennsylvania-based journalist who writes about health, science, and environmental justice, and her work can be found in The Washington Post, Grid Magazine, WIRED and other publications.