Discussions about gentrification in the last few years have largely centered on New York, San Francisco and Washington, D.C., but in Philadelphia last week, the Daily News released a 7,000-word article — a special section of the local newspaper — on how new and long-term residents in the City of Brotherly Love are being impacted by economic disparity and real estate shifts owing to a growing Center City population. In Next City’s “Is Philadelphia in a Housing Bubble?” earlier this month, Emma Jacobs noted that the number of new residential units popping up in 2014 was expected to be nearly five times the number built in 2012, and that “most of it will be luxury and mid-market housing, with monthly rents above the city’s average.”

Now, Ken Steif, a doctoral candidate in the city and regional planning program at the University of Pennsylvania, is adding fascinating visual snapshots to the conversation — along with his markedly hopeful view. Because “neighborhood change in Philadelphia has been a relatively slow process compared to New York and San Francisco,” Steif explains, he thinks the city has an opportunity to become a model of how communities can factor in affordable housing when dealing with economic growth. That requires long-term planning, he says, that will be most effective if city leaders use metrics in addition to remaining open to constituent concerns.

“The term gentrification gets thrown around, and there’s really no scientific definition of it,” says Steif. “Over time it has become a buzzword that instills a lot of very understandably powerful feelings about communities. The approach that I try to take in general, and certainly in this report, is to … allow the data to do the talking.”

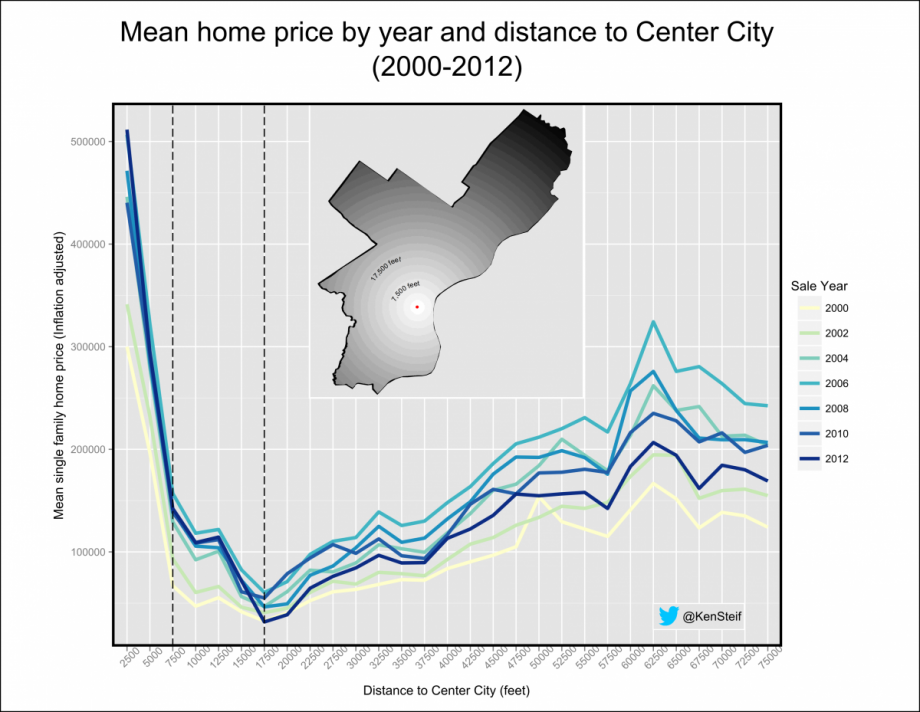

His data sets and maps show how the changes in Philly — Steif relies on single-family home sale prices as the main indicator — have been contained to a few neighborhoods. He notes that while Center City and the area around the University of Pennsylvania are primed to continue rapidly developing, housing prices remain stagnant or depressed just outside the boundaries of those areas.

(Credit: Ken Steif)

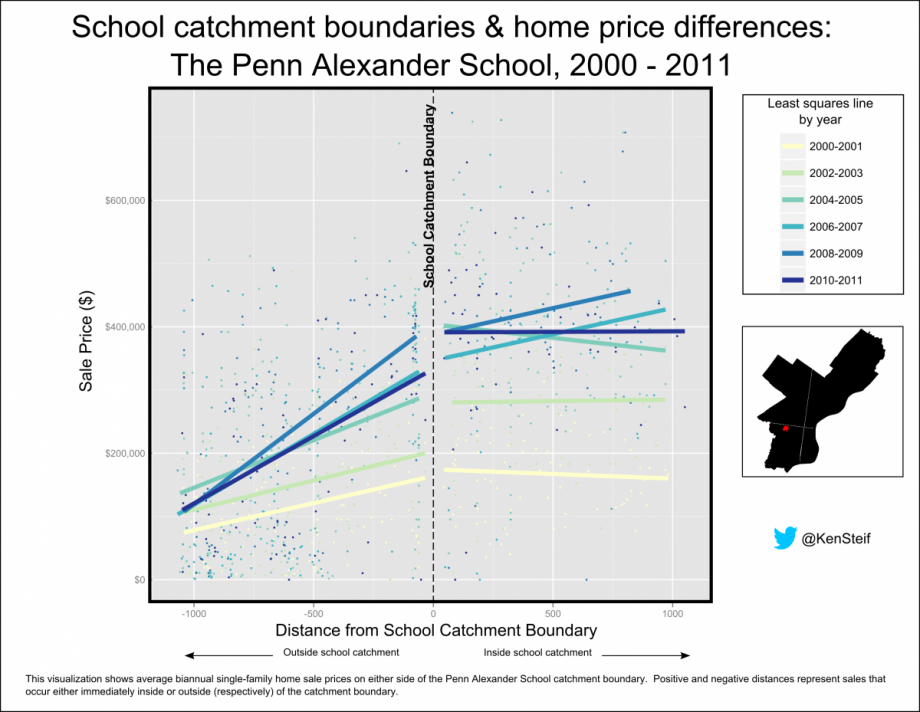

More specifically, Steif looks at how the Penn-subsidized public Penn Alexander school has affected real estate prices narrowly. Noting the “planned wall” that exists around the area of the Penn Alexander catchment zone, Steif writes that the school “symbolizes how the introduction of a quality school where one previously did not exist can be a tremendous driver of neighborhood change.” Yet stray just outside that catchment, and prices have remained stagnant.

(Credit: Ken Steif)

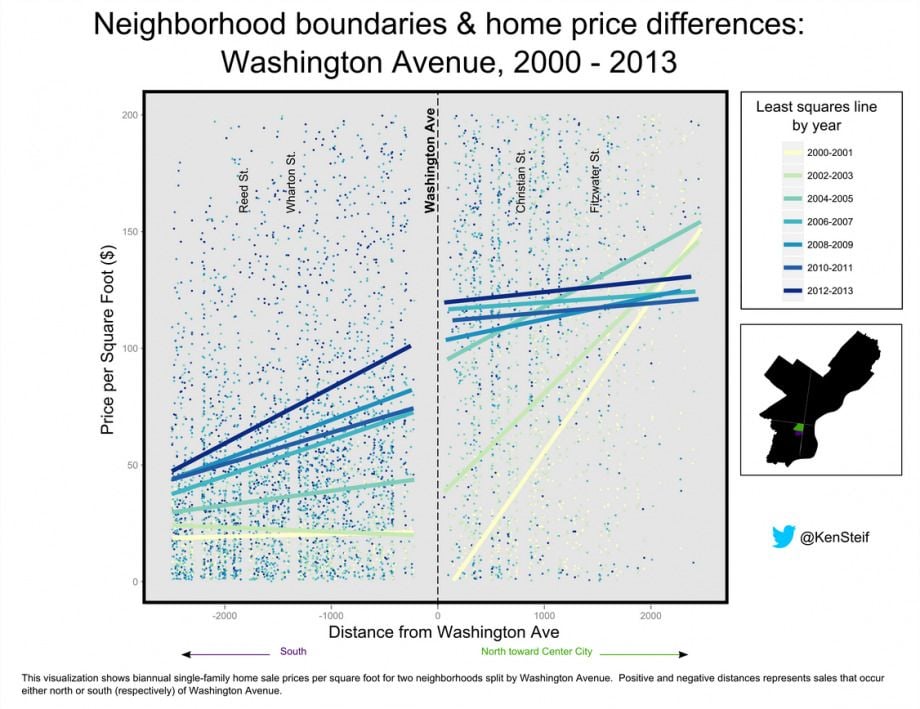

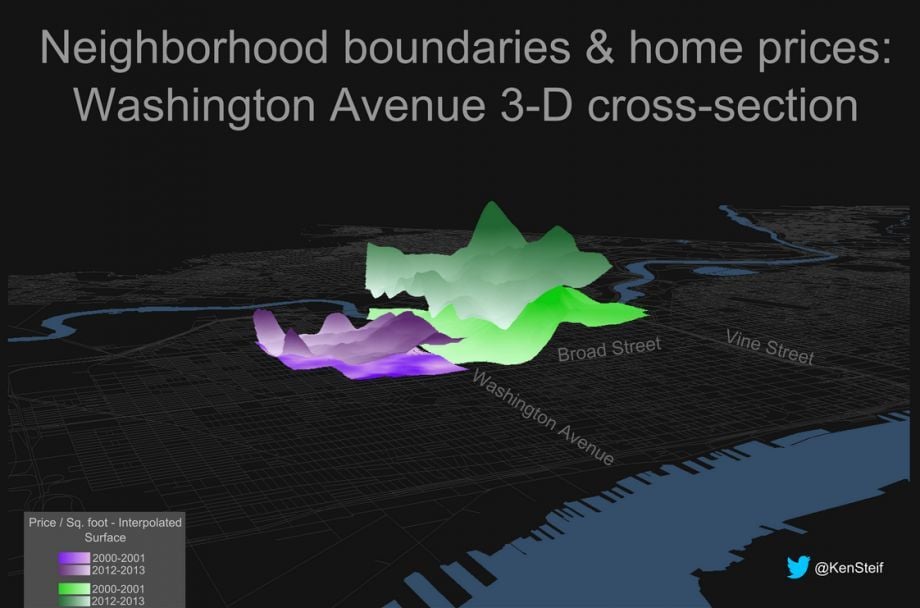

Whereas the Penn Alexander catchment “wall” is more fixed — if you’re outside the zone, your child can’t attend the school — Steif points out that some Philly “walls” are crumbling. The historically commercial/industrial Washington Avenue is becoming a less relevant southern boundary of Center City as people seeking the central district’s arts and culture and dining amenities become more willing to look a little farther outside the immediate area for more affordable prices. Two Steif visuals reflect this, one in 3D.

Steif hopes that the statistical tools and algorithms used in his study can help planners and neighborhood stakeholders forecast future changes to neighborhoods as these walls continue to crumble. “No doubt, these metrics can help guide for-profit investors,” he writes in the report, “but city governments and community developers could also benefit from their use, particularly when developing new interventions to help counter the potential threat of residential displacement.”

He thinks that in the midst of its own upswing, Philadelphia is in the perfect position to deploy those tools.

“Philadelphia has a rare opportunity here, and one they are slowly beginning to capitalize on,” he says. “If the momentum of cities is going to continue, Philadelphia is an example that we can learn a lot from about how to ensure that the benefits of growth are equitably distributed.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Alexis Stephens was Next City’s 2014-2015 equitable cities fellow. She’s written about housing, pop culture, global music subcultures, and more for publications like Shelterforce, Rolling Stone, SPIN, and MTV Iggy. She has a B.A. in urban studies from Barnard College and an M.S. in historic preservation from the University of Pennsylvania.