Call it what you will — creative placemaking, tactical urbanism, social practice art, civic hacking, guerilla urbanism, DIY urbanism, et cetera — all of these practices share a common focus on public space, both in the abstract sense of a democratic public sphere as well as in the concrete sense of a physical place. And yet, too often projects that employ these approaches miss the complex histories of neighborhood public spaces that reflect the multifaceted evolution of social relations among neighbors. Without a strong working knowledge of the social fabric embedded in a particular place it is nearly impossible to create new public spaces, events or programs that involve local residents. Instead, well-intentioned initiatives end up alienating community members, or fostering feelings of invasion or prompting fears of displacement.

Since 2013, we have been researching archival records, conducting oral histories and coordinating public programs in Oakland’s Golden Gate neighborhood. Home and rental prices throughout the Bay Area have spiked sharply in recent years, and the Golden Gate is acutely feeling this regionwide phenomenon. As longtime residents move out, sudden demographic shifts in working-class districts such as the Golden Gate translate into a rapid dissolution of decades-old neighborhood networks. Spaces that once nurtured those connections are forgotten. Such loss is a double erasure — not just of certain people from a place but also of certain places from the neighborhood’s collective memory. In creating new public spaces, planners, architects, designers, artists, policymakers and other initiators would do well to begin their work by looking back to historical acts of placemaking. The following brief descriptions of pivotal public spaces in the Golden Gate’s past and present are examples of why connecting neighborhood legacy with future change is a critical ingredient of inclusive, equitable cities.

When Private Spaces Are Popular Gathering Places

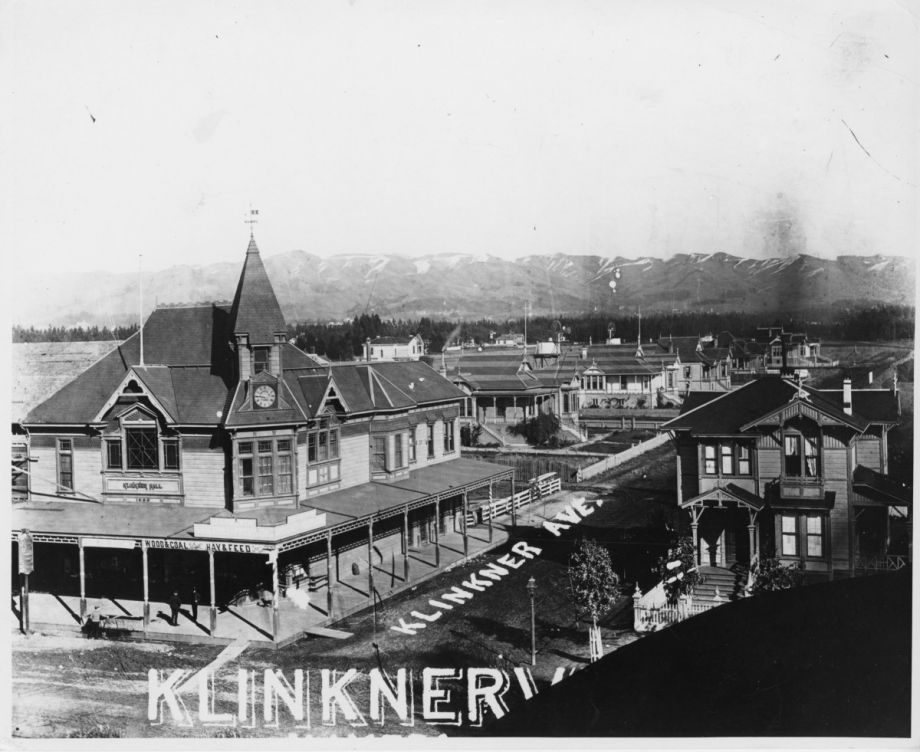

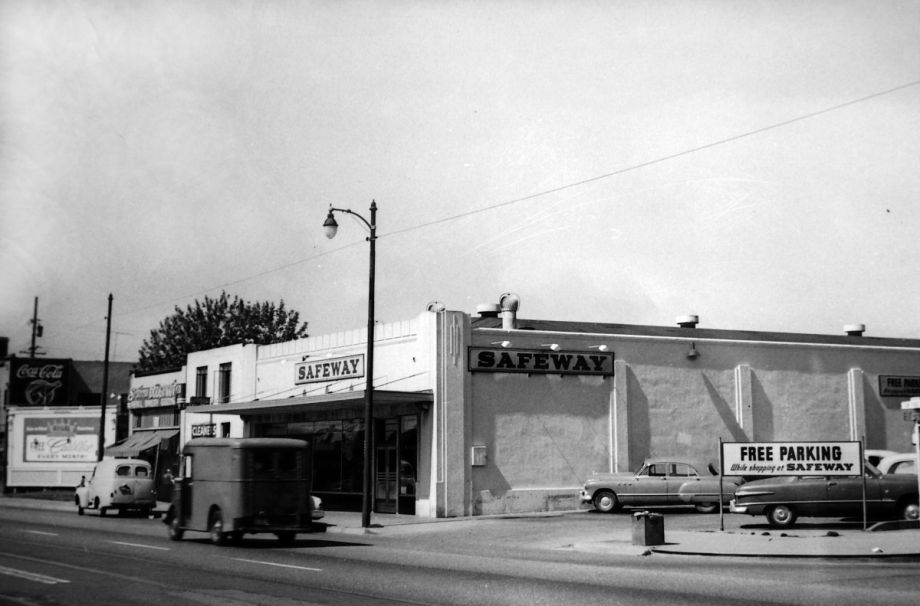

In the late 19th century, Charles Klinkner, an entrepreneur with flamboyant marketing strategies involving painted donkeys and massive signage, initiated the area’s modern real estate development. The self-named town of Klinknerville existed for a few short years before being annexed into Oakland as the Golden Gate neighborhood. In 1885 Klinkner purchased 14 acres of dairy farms to build a number of Victorian homes, some of which still exist. Befitting his ego, Klinkner anchored his new community with a grand public hall. As the region’s largest meeting space, it quickly became the lifeblood of this fledgling town, hosting a variety of gatherings including the Sazerac Lying Club, musical revues and political events. Although privately owned spaces such as Klinkner Hall are not “public space” per se, establishments such as local pubs and markets have historically functioned as popular gathering spaces. During the postwar era, the mantle passed to the Gateway Market, which longtime residents remember fondly for the managers’ personalized attention to neighborhood customers. The market, under different ownership, survives to this day in the same location as the original Klinkner Hall. We have learned through our work that building relationships with the owners and managers of such spaces is essential for understanding the key people, institutions and agendas of the local community.

Top: Historic photo of Klinknerville (Courtesy of Vernon Sappers, Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library); Middle: Historic photo of Gateway Market (Courtesy of the Oakland History Room, Oakland Public Library); Bottom: Map of Golden Gate (Credit: Anisha Gade)

Cities Need “Neutral Spaces”

Since its construction in 1918, the Golden Gate Public Library has mirrored and embraced its surrounding community. That same year, a local family bequeathed to the library the American flag that had been draped over their son’s casket, a WWI soldier killed in action. Encased in glass, this flag continues to adorn the library’s front entrance. In 1926, the local firehouse bell, cast at the de Rome family foundry, one of the Golden Gate’s founding families, was strategically placed on the library front lawn. During the 1990s when many Indian-American immigrants lived in the neighborhood, the library hosted an annual Diwali celebration. And for the past 25 years, the library’s friends group has been coordinating a summer jazz concert series that draws large crowds of current and past residents.

Blurring Public and Private Space

During the Great Migration, spanning 50 years from the early 20th century through the postwar period, more than 6 million African-Americans from the rural South moved to urban areas in the North, Midwest and West. Into this pocket of Oakland (as is true elsewhere), they brought with them the tradition of “block clubs,” a harbinger of today’s neighborhood associations. One of the most active and longest-lasting block clubs in the Golden Gate was on 56th Street. Started by African-Americans in the 1950s, it continued through the 1980s under the leadership of the original founders’ children. Block club meetings transformed residents’ front porches and private living rooms into temporary public spaces that welcomed neighbors living on that block.

Creating Spaces of Refuge

When the crack epidemic struck in the 1980s, the neighborhood’s streets and sidewalks became violent zones occupied by warring street gangs. As public spaces became overrun by crime and the city of Oakland neglected to properly police the neighborhood, many people turned to private space for refuge. One newly formed local religious institution even created its own “members-only” open space by demolishing dilapidated structures on five contiguous plots and consolidating the land. More recently, as the neighborhood recovered from this epidemic, there are inspiring reclamations of public space.

For almost two years, Phat Beets, a local food justice organization, has organized a Saturday market by closing off a small street near the front steps of Destiny Arts, a local dance studio dedicated to youth empowerment. This unlikely location has been transformed into a convivial community hub. Institutions such as a city’s police department, religious centers, and nonprofits, as well as arts foundations like the ones supporting our work can exert a powerful influence on neighborhood public spaces. The lessons that have taken us much longer to understand are the complex dynamics and consequences that such influence sets into motion.

Shambo Meadows (Photo by Lorah Gross)

Today, Golden Gate residents are re-engaging vacant storefronts, empty lots and underutilized streets as well as creating digital forums on sites such as NextDoor. For the most part, these efforts have been largely successful; many new residents are sensitive to and respectful of pre-existing social mores. The real, time-consuming challenge — for newer residents as well as program initiators like ourselves — has been uncovering and understanding the detailed histories and intricate social webs that have evolved over decades. This deeper exploration is essential for creative placemaking efforts to catalyze ethical and equitable development.

Working with the Oakland Public Library, Sue Mark and Anisha Gade will coordinate a series of neighbor-led workshops and installations at the local branch library. Check www.commonsarchive.net for future events.

This article is part of a Next City series focused on community-engaged design made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Anisha Gade is a researcher and urbanist working to develop mixed-methods approaches to understanding public space and the needs of urban communities. Cultural researcher Sue Mark creates socially engaged projects that explore the intersections of lost history and cultural complexities. Commons Archive is the culminating project of their three-year interdisciplinary collaboration in Oakland’s Golden Gate neighborhood. Their work is facilitated through Kala Art Institute’s Print Public, which is supported by the Irvine Foundation, California Humanities, the Oakland Cultural Funding Program and the University of California Chancellor’s Community Partnership Fund.