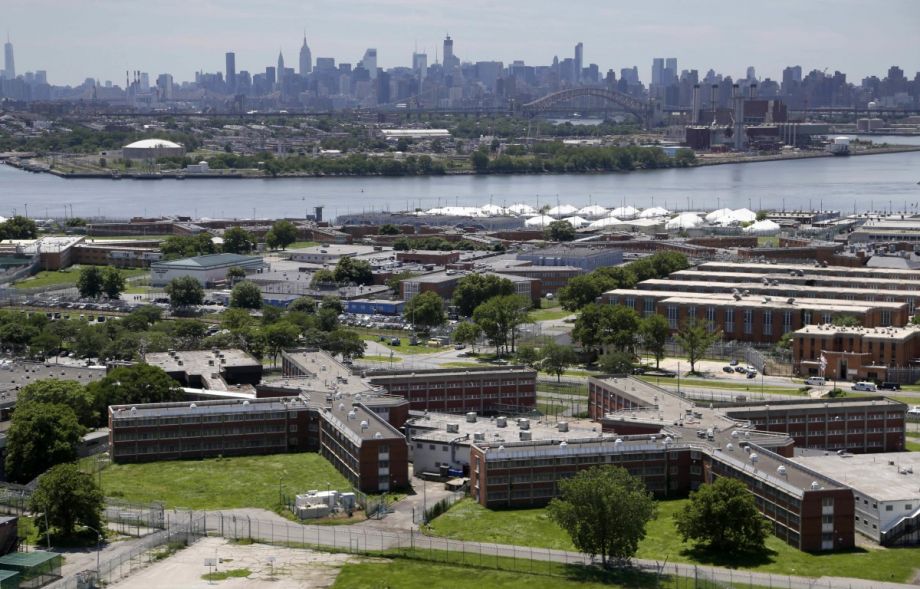

As Hurricane Irene bore down on New York in August 2011, residents living in Flood Zone A and parts of Zone B were ordered to evacuate. That’s when a Mother Jones reporter noticed something odd: Every small island around New York is categorized as either Zone A or B — the two zones with the highest flood risk — except for one: Rikers Island, home to the city’s largest jail. Rikers wasn’t classified as Zone C, either. In fact, it wasn’t categorized at all.

It was a chilling metaphor for the detention center that keeps the vast majority of the roughly 9,700 people incarcerated in New York out of sight and out of mind. Rikers “is not just physically remote — it is psychologically isolated from the rest of New York,” a “19th century solution to a 21st century problem” that “functions as an expensive penal colony.” So found the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, nicknamed the Lippman Commission for its chairman, Jonathan Lippman.

The commission, which was created by New York City Council in 2016, came to a clear conclusion: “We must close the jail complex on Rikers Island. Period.”

This week, Mayor Bill de Blasio unveiled his plan to take their advice. Smaller, Safer, Fairer: A Roadmap to Closing Rikers Island provides a 10-year timeframe for shuttering the 86-year-old jail and replacing it with a borough-based network of smaller detention facilities.

In a way, the plan echoes the less-is-more approach New York has recently taken with other institutions. A few years ago, former Mayor Michael Bloomberg emptied out lumbering “factory-style” high schools of 3,000-plus students and replaced them with smaller ones, raising graduation rates by nearly 10 percent.

Little research has been conducted to indicate whether smaller jails would produce similar outcomes. U.K.-based prisons expert Kevin Lockyer has found that “the key determinant of … effectiveness of a prison was not its size, but its age.” Nevertheless, the Lippman Commission has offered a radical reimagining of what a New York City jail could be like. Utilizing a “clustered housing” model — a sort of mixed-use development style for jails — it found that each unit should ideally contain between 32 and 56 beds, “enabling correction officers … to develop a relationship with residents and work with them to maintain order.”

Some tough-on-crime Americans might scoff at the idea of guards and “residents” developing a friendly rapport as hug-a-thug sentimentality. But it’s been shown to work in Norway, where smaller, more modular jails allow “guards [to] socialize with the inmates every day, in casual conversation, often over tea or coffee,” according to the New York Times. In this environment, violence and threats rarely occur. Norway’s Bastoy Prison — now renowned thanks to its portrayal in Michael Moore’s documentary “Where to Invade Next” — features bright, airy, IKEA-like spaces, and de Blasio’s plans aim to replicate this soft touch. The Lippman Commission’s recommendations include everything from upholstered furniture to carpeting to porcelain toilets with seats, an acknowledgment that “basic human needs shape behavior.”

Only one other major detention center in the U.S. has embraced such Japandinavian design: San Diego’s Las Colinas Detention and Reentry Facility. The 1,216-bed, LEED Gold-certified women’s prison completed Phase One of construction in 2014, and though studies have yet to be conducted on how its college campus-like architecture affects inmate behavior, its typically critical state-mandated annual review singled out Las Colinas as “a model jail.”

Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of the Rikers rethink, however, is the notion of extracting thousands of inmates from a forlorn watery outpost and scattering them across the city. The plan to decentralize New York’s jail population adheres closely to the Lippman Commission’s recommendations, which advocate for a “system of smaller state-of-the-art jails … situated near the courthouses they serve.” The more dispersed network should make visitation by family and attorneys easier, cut transportation and maintenance costs, simplify court appearances, and streamline inmate processing.

As expected, this part of the plan has awoken the dark forces of NIMBYism, which mobilized to deflect any chance of a jail coming within eyeshot of their kitchen windows. But this knee-jerk reaction ignores the fact that such smaller jails are already a part of the cityscape, and coexist peacefully — and inconspicuously — with the areas around them. A visitor could be forgiven for walking right by the Brooklyn Detention Complex without noticing it. The facility, on bustling Atlantic Avenue in the tres chic neighborhood of Boerum Hill, looks pretty much like any other municipal building except for the bars on the windows, which themselves are easy to miss. That’s the thing about jails: They like to keep the action inside.

Advocates for the incarcerated have generally greeted the Rikers plan with optimism, though a few have argued the 10-year timeframe is too long. (The city says it’s already tight.) One intriguing criticism voiced on Twitter argued that closing Rikers is a red herring to distract from the real problem: a criminal justice system that targets minorities. The same person even argued that Rikers Island has value as a symbol of American injustice: “If you decentralize detention … it becomes harder to resist. You don’t have one blightful hell hole to resist.”

But the plan does have policy implications, the biggest of which might be that the city will be forced to reduce Rikers’ population by about half to make demolishing it possible. New York — which already has a lower jail incarceration rate than any other large U.S. city — will lean more on diversion programs, home confinement and electronic monitoring, reserving jail space “for individuals who are facing very serious charges or who pose a high risk of flight,” according to the mayor.

In other words, rather than rely solely on policy to thin its jail population, New York will shrink the jails themselves in a way that will force policy to follow. Los Angeles County has debated a similar fix by proposing to rebuild its version of Rikers Island, the Men’s Central Jail, with fewer beds than before. A smaller jail would be “a serious inducement to the Sheriff’s Department and other county officials to view incarceration as a last resort,” argued the Los Angeles Times. Or put more succinctly: “If you build a jail, they will fill it.”

Will Doig was formerly Next City’s international editor. He's worked as a columnist at Salon, an editor at The Daily Beast, a lecturer at the New School, and a communications staffer at the Open Society Foundations. He is the author of High-Speed Empire: Chinese Expansion and the Future of Southeast Asia, published by Columbia Global Reports.