Kathleen Webster lived on Forsyth Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in the late 1970s, when her neighbors started organizing around Sara D. Roosevelt Park. Everything around it was boarded up and closed.

“This community got on bicycles, did a whistle campaign. They organized themselves to take the park back from pimps and drug dealers,” she says.

The police, and eventually the parks department, were more than happy to work closely with the community, Webster remembers. “At the time, they were happy actually to have anybody take it on, because nobody else wanted to be here,” she says. “As one person told me, a parks employee threw the keys at him for a back gate, and said ‘do you want to take care of this?’”

Take care of it they did, Webster and her neighbors. They focused their initial energies on one section of the narrow but long park and transformed it into the BRC Senior Center, which is now surrounded by the Elizabeth Hubbard Memorial Garden (named for one of the original volunteers). The site became the anchor to gradually wrest the park back to healthy, productive community use. Webster, who still lives in the neighborhood, became president of the Sara D. Roosevelt Park Community Coalition, which continues to organize around the park.

But times have changed. The Lower East Side is now one of the hottest real estate markets in Manhattan. Public assets, including parks, park buildings, former schools, library buildings whether they’re in use or not, community gardens and city-owned vacant lots are suddenly in the crosshairs of developers who once wouldn’t touch the neighborhood. Now the volunteers who worked to make the area safe are left wondering: How can they get the attention of public officials when people with deep pockets are drawing up plans and proposing shiny designs for repurposing public assets that seem otherwise underutilized?

“If you think of development as a race, with a starting line and a finish line, in too many communities, government starts at or slightly ahead of the starting line, the developer’s usually way down the road, and the communities aren’t even at the starting line,” says Susan Lerner, executive director of Common Cause New York, the state chapter of the national civic engagement and government accountability organization.

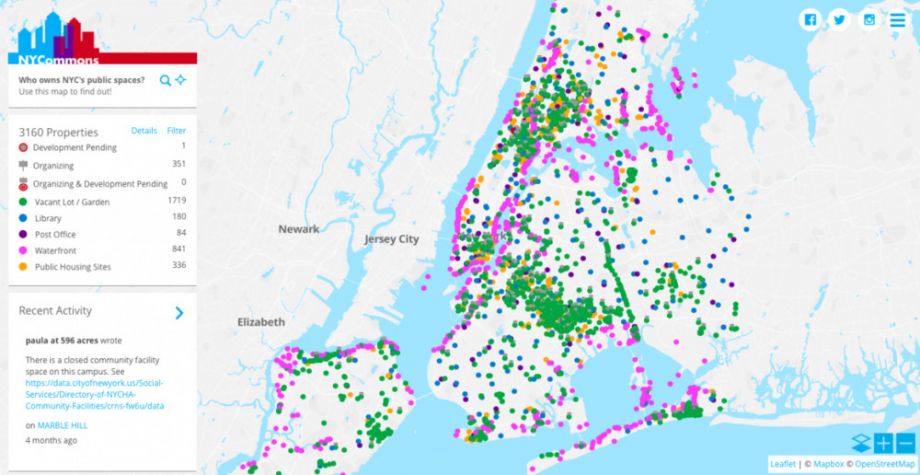

Common Cause New York has been collaborating with the Community Development Project at the Urban Justice Center and 596 Acres on the NYCommons initiative to build a modern set of organizing tools to help grassroots groups compete with private real estate developers when it comes to determining the future of publicly owned assets across the city. One of those tools is a new online map and database of all the public assets that, while hard to define, essentially provide some type of potential real estate development opportunity — something a city agency could potentially sell or lease to someone else.

“The baseline thing we need to do is figure out what the set of things is that we’re trying to include in this conversation,” says attorney Paula Segal, founder of 596 Acres, which supports grassroots organizing around vacant publicly owned lots in NYC. “The truth is, we’re in a city, most of our infrastructure and our assets are shared — the subways, the roads, the sidewalks, the water, something like 30, 40 percent of all housing in the city is some form of cooperatively owned. The list goes on and on to the point where privately owned property can start to seem like the real outlier.”

The NYCommons map is a work in progress as city records and other documentation continue being parsed for accuracy. (Credit: NYCommons)

Residents like Webster and her neighbors have long been organizing around many of these assets. About three or four years ago, Lerner says, Common Cause and the other NYCommons partners started to see a pattern in the organizing against a proposed soccer stadium taking away public park space in Queens, around the Midtown Library in Manhattan, and around the future of the main Brooklyn Public Library Branch and other public assets.

“It seemed as if each one of these particular issues was being attacked as if it was a free-standing issue, and the people working on it were thinking of it as ‘this is a parks issue, this is a libraries issue,’” Lerner says. “We started thinking about the fact that all of these separate challenges had similar underlying policy issues that have to do with how does government think about commonly owned, shared assets.”

Residents were spending huge amounts of time and energy, often to no avail for some of these larger proposals and projects involving public assets.

Meanwhile, when it came to vacant lots, over nearly the same two-year period, grassroots groups in four of the five boroughs successfully organized around 36 former publicly owned vacant lots, which were officially declared permanent public parks at the end of 2015. 596 Acres supported 17 of those grassroots groups.

“We were able to get new parks created by getting people involved very early on before anybody talked about flipping anything in vacant, publicly owned real estate assets in their own neighborhoods, transforming them into community resources that maybe weren’t recognized as permanent when they were created, but they became permanent,” says Segal.

596 Acres has developed a number of tools and found or created resources specifically around city-owned vacant land, including its own online map and database, Living Lots NYC, that provides a useful platform for organizers to connect and maintain records of organizing activity around each lot. NYCommons hopes to create an expanded tool set to serve grassroots organizing around the broader universe of public assets in NYC.

They started by asking. NYCommons went to 10 neighborhoods over the spring and summer where they knew people were organizing. Lerner says they found “a tremendous amount of energy in all five boroughs” for sharing best practices and connecting with others doing similar work.

NYCommons picked three neighborhoods for pilots, and provided them documentation, workshop facilitation and other resources to begin developing a tool kit. Many resources already existed, thanks to groups like the Center for Urban Pedagogy or New Yorkers for Parks. The Sara D. Roosevelt Park Community Coalition was one of the pilot sites.

“Movement happens in funny ways, but the NYCommons materials were very helpful as a draft basis from which to go,” says Webster.

The coalition’s current focus is a former recreation center, currently used as a systemwide parks storage facility, smack dab in the middle of a well-used area of the park. “We’ve been having a conversation about this building since 1994,” says Webster.

The group had already successfully lobbied local Council Member Margaret Chin and Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer to earmark $1 million for renovations to the building, but the parks department has yet to propose a new purpose for the building. Webster credits NYCommons for helping get through this most recent round of community visioning for the site. Chin testified at a recent hearing that she supported one of the coalition’s ideas to turn the facility into a daytime drop-in center for the homeless.

Efforts by Webster and the other pilot sites around the city will continue to shape the final NYCommons tool kit and the online platform. Many sites already have data from recent years’ organizing efforts that need to be uploaded. The organizing track records themselves provide vital talking points for future hearings and op-eds and community meetings.

“There’s a real hunger for this in neighborhoods of all different backgrounds,” says Lerner. “Hopefully NYCommons can provide an entrée into a fairly sophisticated, experienced, citywide network of groups who are all thinking along the same lines, putting pressure on government to be responsive, with a similar vocabulary and set of expectations about public assets serving the public.”

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)