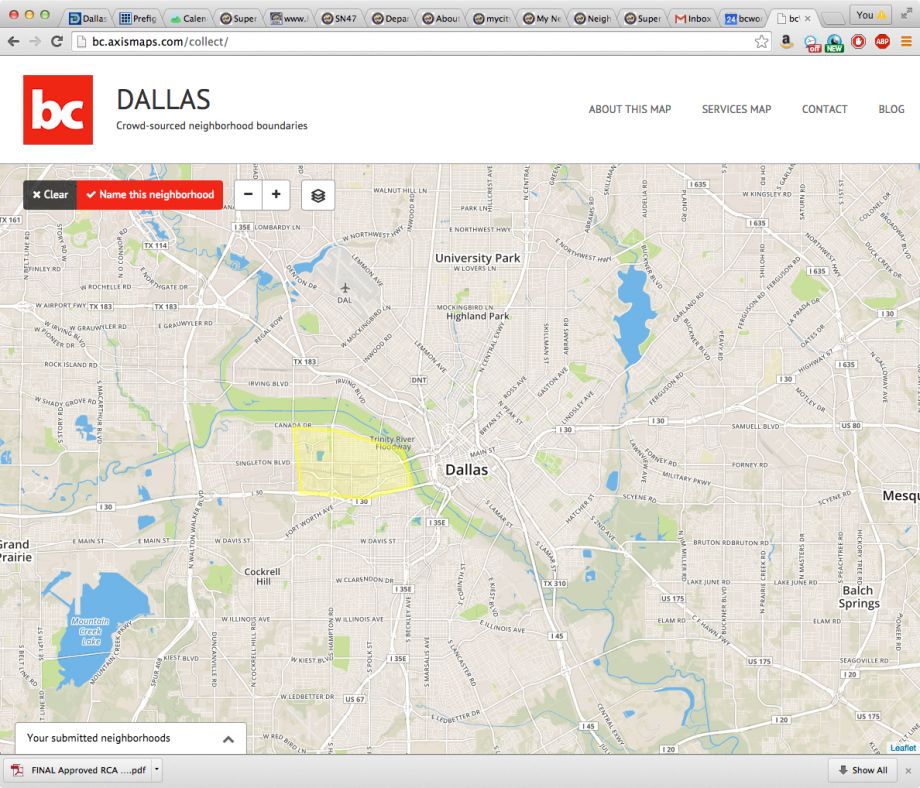

Three times already this year, local news stations have incorrectly identified a particular Dallas neighborhood, Pleasant Grove, as the scene of violent crimes that actually occurred in other neighborhoods. This is one of several reasons I’ve spent the last year asking Dallas residents to draw maps of their neighborhoods. The effort, launched two years ago by the nonprofit where I work, mirrors similar initiatives across the country, in cities including New York, Chicago and Portland. By crowdsourcing neighborhood boundaries, residents can put themselves on the map in critical ways.

Why does this matter? Neighborhoods are the smallest organizing element in any city. A strong city is made up of strong neighborhoods, where the residents can effectively advocate for their needs. A neighborhood boundary marks off a particular geography and calls out important elements within that geography: architecture, street fabric, public spaces and natural resources, to name a few. Putting that line on a page lets residents begin to identify needs and set priorities. Without boundaries, there’s no way to know where to start.

Knowing a neighborhood’s boundaries and unique features allows a group to list its assets. What buildings have historic significance? What shops and restaurants exist? It also helps highlight gaps: What’s missing? What does the neighborhood need more of? What is there already too much of? Armed with this detailed inventory, residents can approach a developer, city council member or advocacy group with hard numbers on what they know their neighborhood needs.

With a precisely defined geography, residents living in a food desert can point to developable vacant land that’s ideal for a grocery store. They can also cite how many potential grocery shoppers live within the neighborhood.

In addition to being able to organize within the neighborhood, staking a claim to a neighborhood, putting it on a map and naming it, can help a neighborhood control its own narrative and tell its story — so someone else doesn’t.

Our neighborhood map project was started in part as a response to consistent misidentification of Dallas neighborhoods by local media, which appears to be particularly common in stories about majority-minority neighborhoods. This kind of oversight can contribute to a false narrative about a place, especially when the news is about crime or violence, and takes away from residents’ ability to tell their story and shape their neighborhood’s future. Even worse is when neighborhoods are completely left off of the map, as if they have no story at all to tell.

Neighborhood mapping can also counter narrative hijacking like I’ve seen in my hometown of Brooklyn, where realtor-driven neighborhood rebranding has led to areas being renamed. These places have their own unique identities and histories, yet longtime residents saw names changed so that real estate sellers could capitalize on increasing property values in adjacent trendy neighborhoods.

Cities across the country — including Dallas, Boston, New York, Chicago, Portland and Seattle — have crowdsourced mapping projects people can contribute to. For cities lacking such an effort, tools like Google Map Maker have been effective.

Mapping your neighborhood is a simple but powerful activity that can quickly change how you perceive your daily surroundings. If you don’t know your neighborhood boundaries, start with a walk around where you live and note hard boundaries like rivers and large roads, changes in the street grid, or shifts in architectural styles from one block to another. What stands out? Might those shifts or significant markers constitute a boundary? Once you’ve made those observations, or if you already know or have some ideas about what your neighborhood boundaries are, you can start literally putting yourself on the map.

Maps are powerful tools. They help us navigate unfamiliar places. They document current conditions of our built and natural environment. They tell us incredible stories about the past. And just like history, they’re extremely subjective (and sometimes downright factually inaccurate). When a map is made, whoever is making it decides what’s in and what’s out. Those decisions can have real consequences. It should be experts making those decisions — and what better neighborhood experts than local residents themselves.

Lizzie MacWillie, a Dallas Public Voices participant, is senior design manager at buildingcommunityWORKSHOP, a nonprofit community design center.