Digging in the public right-of-way in Chicago — or in any city — can be a risky proposition. According to the American Public Works Association, an underground utility line is hit every 60 seconds in the U.S., in part because many renditions of underground assets don’t record depth. When planning a dig, utility companies and city departments have had to accept a degree of the unknown.

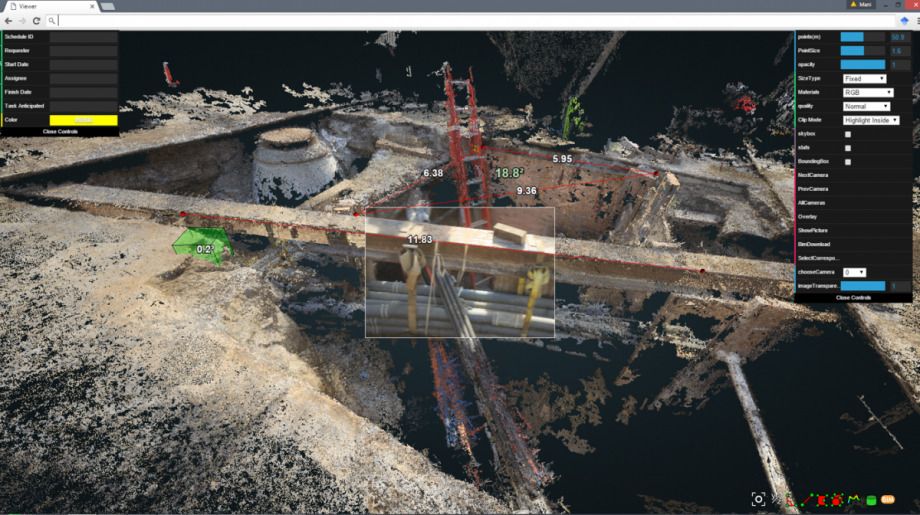

Now a Chicago consortium of public, private and university entities are piloting a digital 3D rendering system that aims to map underground Chicago by anchoring existing maps to real-life conditions. When a hole is opened up for a dig, the mass of exposed pipes and lines will be photographed by walking the perimeter — with just a smartphone camera — and digitally rendered in all three dimensions. That one rich node of data can then be used to extrapolate about the depth of pipes, utility lines and other assets as they extend away from the opening.

“Before you couldn’t see the assets that were under the other assets. You couldn’t see a fiber line hiding under a water main, for example,” says Steve Fifita, executive director of the City Digital consortium. So “when you dig in Chicago, you invariably run into things, whether it’s gas lines, power lines.”

The group aims to use Chicago as a test for new smart city technologies by bringing together startups, academics and city departments to solve specific problems. In this case, the tangle of underground infrastructure and the imprecise data on it, “wasn’t an unknown problem, it was actually a problem that was viewed as unsolvable,” says Fifita.

Brenna Berman, Chicago’s chief information officer, says she’d been aware of the issue from her first years with the city, when she would witness several departments overlaying tissue-thin maps to try to plan digs. The process has evolved since then, but it’s remained a challenge with no easy off-the-shelf solution. When City Digital formed (Berman was involved in the creation) the problem of underground assets was one of her first suggestions for a nut to crack. “And it’s turned out to be frankly the perfect type of problem to solve in this co-development type of environment,” she says.

For this project, it took a certain type of database already developed by Microsoft, an experimental photographic processing model from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, a data visualization tool from a Chicago startup, and a variety of other technologies for data security, role management and more.

“These were all technologies that existed but at various levels of product availability,” says Berman, and they’d never been used in quite this way before. After the six months it took to choose the best products for each need, the challenge was making them work together. City Digital tested it on a single intersection, and when it checked out, the question became “are they going to work on a large urban scale?” asks Berman. A three-city-block pilot launched last week.

But whether the technology itself scales up isn’t the only question. The process also needs to scale. Digs in Chicago are managed by the Office of Underground Coordination. Would requiring the department to use this technology before approving every project take too long? How should the contracts between the city, Microsoft, Accenture, utility companies and other partners be worked out? There’s also the looming question of data and access. Some assets are owned by the city, others by Chicago’s privately owned utility companies. Knowledge about the precise location of water mains, gas lines and internet fiber are deeply sensitive. This isn’t going to be public data, and it won’t even be accessible for every member of the consortium who worked on the project.

“We’re actually not trying to increase transparency with this project,” says Berman, “and that is an odd thing for the CIO of Chicago to say.”

There’s also the matter of marketability. Chicago is a customer for this product, but it’s also a part of the consortium developing it, and the goal here is to eventually market the technology to other cities. “We are absolutely after revenue generation here,” says Berman.

Fifita suggests the business model might look something like LinkedIn: Cities wouldn’t pay to use the platform, but engineering and utility companies would. Berman says it’s not yet clear how payment would work in Chicago or other cities, especially given that all cities manage digs differently, and some cities own their utilities while others don’t. She also points out that the majority of the time, the city is permitting its own departments, like the water department, for digs in the right-of-way. Chicago’s own water department has expressed excitement about using this technology during the dig planning phase.

Interestingly, because Chicago is both co-developer and customer, the city won’t actually use both sides of the technology. There’s one component for mapping the assets, and another for visualizing them. Chicago has its own data visualization program, so the city made sure to advocate that the front-end and back-end technologies weren’t too tightly coupled. Now other cities will have the option to purchase just one or the other too.

All of this, if it can be scaled, should decrease delays and project costs, while improving safety. In worst-case scenarios, “these accidents do hurt people,” says Berman, if, for example a gas main is struck. Or projects may take longer than anticipated, delay traffic and rack up costs. Right now, “there’s a high level of unknown,” says Berman. “This project will decrease that unknown.” The three-block pilot will run for two months.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)