Punch in “Westlands, Nairobi, Kenya,” on Google Maps and the world’s most popular map will populate a street grid with regular intersections, the shaded image of a dozen buildings per block, and pins galore: Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi Stock Exchange, Java House, Standard Chartered Bank and countless others. Switch over to Satellite mode, and the view looks roughly the same as those shaded buildings became photographic images of tidy business parks and elaborate high rises.

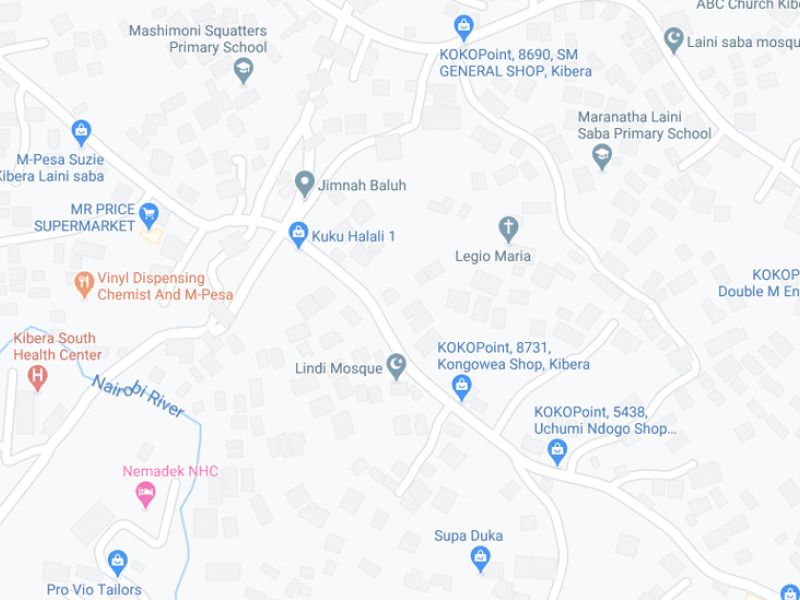

Do the same for “Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya,” and the contrast is striking. Google Maps will populate a handful of intersecting streets, the shaded image of a few hundred buildings, and pins for a dozen odd locations like the Lindi Primary School, Laini Saba Mosque and ABC Church Kibera. But in Satellite mode, the view looks dramatically different: Thousands of buildings packed tightly together connected by narrow alleyways.

Why do Map and Satellite views line up in Westlands but not in Kibera? Because the former is a formal neighborhood — where streets were laid out, land was divided into plots, and formal title was issued to landowners — and the latter is an informal neighborhood — where early-20th century migrants from the Kenyan countryside squatted and built their own houses on forested land that was then on the outskirts of the city. As a result, neighborhoods like Kibera lack an adequate street network. UN-Habitat estimates cities need to allocate at least 30 percent of their land area to streets in order to have a functioning city. Streets mean buildings have addresses, piped access to water and sanitation, legal land title with records that allow cities to generate tax revenue, easy access to fire trucks and ambulances, and other vital municipal services.

Approximately one billion people live in Kibera-like situations around the world, according to UN estimates. Last year, urban researchers, cartographers, and computational experts at the University of Chicago puzzled over a basic but complex question: Can we map their neighborhoods and estimate where they need streets in order to catch up with their formal counterparts?

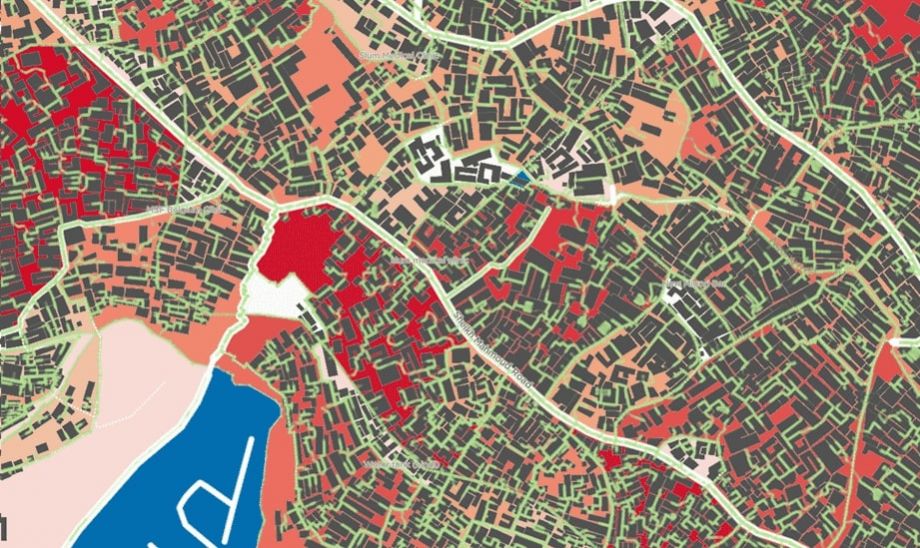

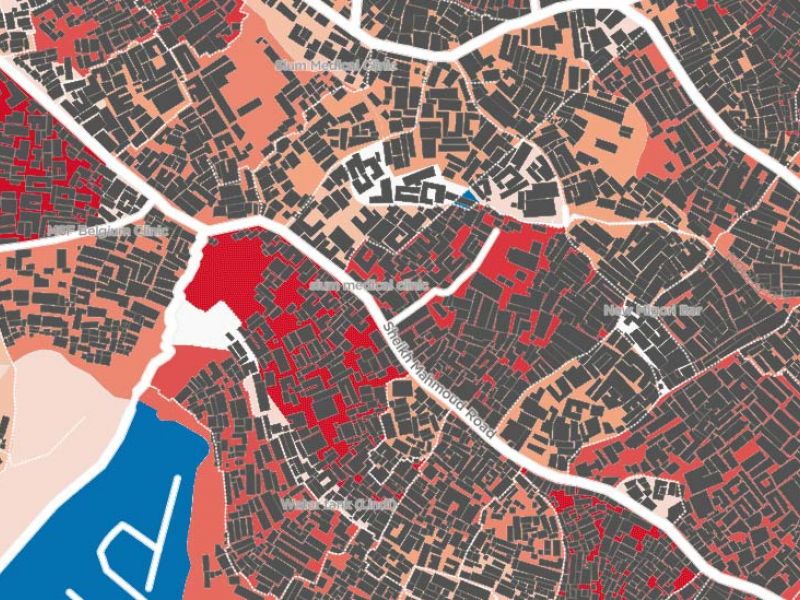

The result is the Million Neighborhoods map, jointly published by the university’s Mansueto Institute for Urban Innovation and the Research Computing Center late last year. The map color codes every city block in the developing world on a scale from red (very limited access) to blue (high access). In Nairobi, for example, Westlands populates in blue shades of mostly moderate to high access, while across town Kibera is a series of deep red blocks.

“We divided the earth into city blocks and found that about a million neighborhoods don’t have adequate infrastructure,” explains Mansueto Institute inaugural director Luis Bettencourt.

The Million Neighborhoods map color-codes neighborhoods on how they rank on street access. Then, the app algorithmically generates proposals for where to add streets without removing any existing buildings. (First screenshot; Map data ©2020 Google / Second screenshot via Million Neighborhoods)

Zoom in on any red block and the Million Neighborhoods map goes one step further than the blank spaces between streets on Google Maps. Green lines — algorithmically generated proposals for weaving a pattern of streets between buildings — appear. Suddenly, buildings completely cut off from the surrounding block have a clear pathway.

“Slums are predicated on this problem of lack of access,” Bettencourt says. “So for each city block, we algorithmically propose a minimal network.”

Such a bold cartographic vision would have been impossible to generate until recently thanks to new technological advances in remote sensing and computing power. Ever higher resolution spatial photography from satellites and drones has enabled user-generated projects such as OpenStreetMap, the so-called wiki of maps, where volunteers use photos to trace buildings onto maps, especially in the wake of humanitarian crises. These efforts have produced baseline maps for the kinds of informal settlements that Million Neighborhoods hopes to take one step further by highlighting where there are gaps in street infrastructure.

Generating the Million Neighborhoods map used to be painstakingly slow. “When we started, it took many weeks to produce small parts of the map,” Bettencourt says. But as computing power improves to tackle big data problems like Million Neighborhoods, these maps can now be produced with a much faster turnaround.

Bettencourt readily admits that the map’s envisioning of how to provide basic urban infrastructure to one billion people living in informal settlements is undeniably a broad-brush effort. “It just gives you this bare estimate without moving the buildings,” he says. At the individual block level, the map’s proposal to forge a street through a dense neighborhood may imply bulldozing beloved landmarks. It conjures up the specter of a 21st century version of urban renewal, wrought by algorithm rather than by planner.

To that end, Bettencourt emphasizes that Million Neighborhoods is not a prescription but rather a thought exercise to make the seemingly insurmountable challenge of addressing the world’s urban informal population appear more manageable.

“Is is very easy to feel paralyzed,” Bettencourt says. “Our whole logic is that you can deal with this problem of access by one city block at a time. You can deal with the world one neighborhood at a time, a million times.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: We’ve corrected the spelling of Luis Bettencourt’s name, as well as his title.

Our special correspondent Gregory Scruggs will be in Abu Dhabi to cover World Urban Forum 10, taking place February 8 through 13, 2020. To stay on top of the essential conversations and innovative solutions presented at WUF 10, sign up for Urban Planet, our global sustainability newsletter.

Gregory Scruggs is a Seattle-based independent journalist who writes about solutions for cities. He has covered major international forums on urbanization, climate change, and sustainable development where he has interviewed dozens of mayors and high-ranking officials in order to tell powerful stories about humanity’s urban future. He has reported at street level from more than two dozen countries on solutions to hot-button issues facing cities, from housing to transportation to civic engagement to social equity. In 2017, he won a United Nations Correspondents Association award for his coverage of global urbanization and the UN’s Habitat III summit on the future of cities. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.