How do you get a city more accustomed to biking trails to pedal the streets? Paint a whole lot of lanes.

Macon, Georgia, population 150,000, was able to increase cyclist counts nearly tenfold during a one-week pop-up bike network, which at 8 miles, may have been the largest such temporary installation ever.

Macon has had an 11-mile riverfront trail, where cyclists can travel from historic monument to playground to park without ever touching a street. But that, says Josh Rogers, president and CEO of the nonprofit NewTown Macon, which works to revitalize the city’s downtown, was exactly the problem. “People drive to the trail and then unload their bike and ride.”

The thought that there might be a better way stemmed from a 2015 trip to Copenhagen (funded by the Knight Foundation and organized by 8 80 Cities, an international mobility-focused nonprofit).

“It was like a lightbulb moment,” Rogers recalls. “We love biking along the river, why don’t we do this along every street?” At the time, Macon had exactly three blocks with “some form of bike infrastructure” in its downtown, “and they weren’t connected. They’re three random blocks,” Rogers says. On an average day, the number of people riding bikes in downtown Macon was 23.

In an effort to change that, NewTown, 8 80 Cities and other partners in and outside government decided to test on-street biking at a large scale and won a $150,000 grant from the Knight Cities Challenge to implement the project.

“Then we had to figure out how to actually do it,” Rogers says. They got advice and help from Jason Roberts of Better Block, which focuses on healthy built environments.

Roberts admits that the biggest pop-up bike infrastructure they’d put in prior to Macon’s was less than a mile long. “I didn’t find that out until we were out laying out the path.”

Regardless, 498 cans of paint, five days, 80 volunteers and 180 bollards later, the pop-up bike network was open. It was intended to be a weekend-long test, but when Mayor Robert Reichert cut the ribbon, he declared it would stay up for a week.

The project also coincided with the launch of Macon’s bike-share program.

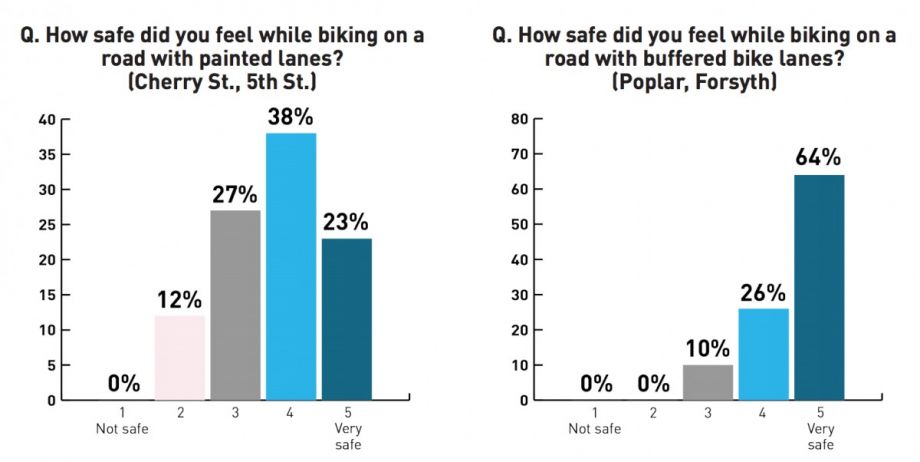

NewTown and partners tested five kinds of bike infrastructure, from sharrows or a painted stripe, to more buffered lanes as well as protected cycletracks with bollards, says Rossana Tudo from 8 80 Cities. They found that the protected lanes were by far the most popular, accounting for four out of five rides.

(From Macon Connects)

During the weeklong pop-up in September, average bike counts increased nearly tenfold, to 217 daily. And “the vast majority of people [using the bike network] had never been on a protected bike lane, ever,” says Roberts.

Data were collected with four counters along the lanes as well as three volunteers who recorded the demographics of cyclists using the infrastructure. According to a wrap-up report, Macon’s black residents, who make up 53 percent of the population, were underrepresented on the pop-up’s lanes by 21 percent, and the “data reveals that there needs to be more effort dedicated to ensuring that bike infrastructure links to different neighborhoods and connects residents of all racial backgrounds.” There’s also a note about how few people over age 55 and younger than 17 participated, and that “the ideal bike network should appeal to those across the age spectrum.”

These will all be factors to consider as Macon moves toward making the bike lanes permanent, which was supported by a majority of residents surveyed as well as political leadership. The infrastructure expansion will, of course, take more time and money.

“It’s hard to explain to you what a massive shift [this has been]. From ‘Oh, people aren’t going to bike, we put in a block and nobody used it,’ to now they know what good infrastructure looks like, and they’re going to use it,” says Rogers.

“I think what was remarkable about the fact that we did this in Macon,” says Tudo, “was that driving there is actually quite nice. There’s not a lot of traffic. There isn’t a crisis of gridlock that is causing people to rethink mobility. But there are leaders in the city who don’t want to wait around until there is a crisis.”

Rachel Kaufman is Next City's senior editor, responsible for our daily journalism. She was a longtime Next City freelance writer and editor before coming on staff full-time. She has covered transportation, sustainability, science and tech. Her writing has appeared in Inc., National Geographic News, Scientific American and other outlets.

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)