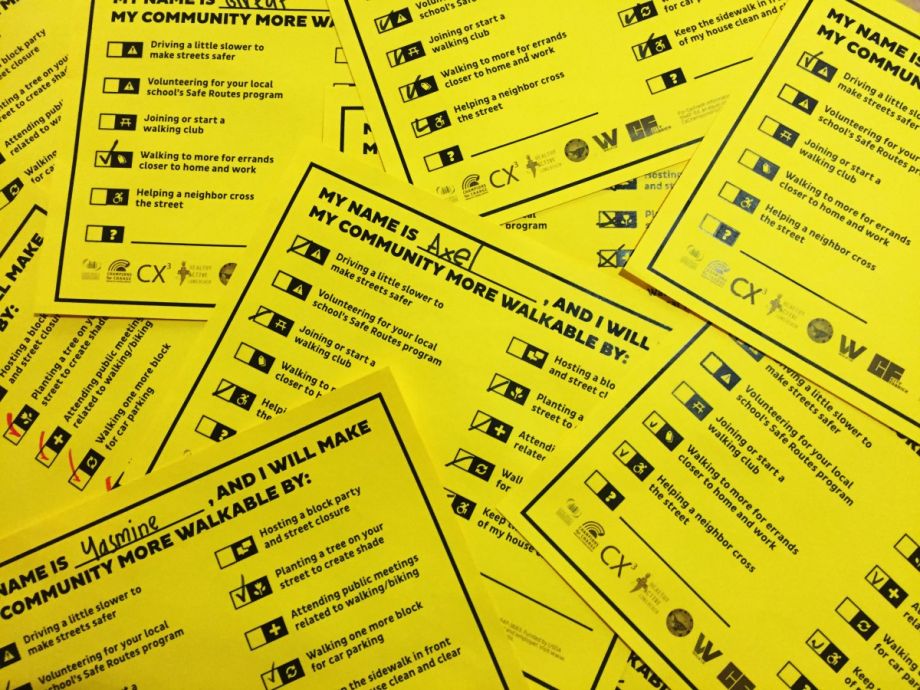

Last summer, at a city-run day camp for kids and teens in Long Beach, California, bright yellow pledge cards were passed out to around 120 campers. The pledge read: “MY NAME IS _________ AND I WILL MAKE MY COMMUNITY MORE WALKABLE BY…” A list of options followed, such as driving more slowly, creating a walking club, helping a neighbor cross the street, and keeping the sidewalk clear in front of their homes.

“Kids have a great sense of how to navigate their neighborhood by foot,” says Brian Ulaszewski, executive director of City Fabrick, the local nonprofit urban design studio and advocacy organization that produced the pledge cards. “Yet they are rarely asked to participate in making it better.”

This year, Ulaszewski and his team wrapped up a two-year project to create the first Pedestrian Master Plan for Central Long Beach. The effort is historic in two ways — both as the first master plan for pedestrians in a part of the city near its port, where the needs of industry have long reigned supreme, and as a pioneering collaboration with community for the small city that sits on the southern border of Los Angeles.

City Fabrick worked in in close collaboration with the Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), who had identified ten low-income areas with high public health needs in the city’s central and west side neighborhoods, near the Port of Long Beach, for their Communities of Excellence (CX3) Project. The CX3 Master Plan seeks “equity for all walkers” by improving walkability and access to healthy foods.

The design studio and health department have found success with playful and collaborative community engagement tactics, like the pledge cards, for researching the Pedestrian Plan. But their methods have another intention: to reach a wider span of residents, especially those often left out of planning processes, by making participation as easy as possible, and empowering them with the skills and materials to assess and analyze their own streets.

Walkability pledge cards (Credit: City Fabrick)

“The kids came up with such great, creative suggestions that we never could have prescribed for them,” says Lara Turnbull, project director at the DHHS. “They were so excited and took such ownership. And when they left with a pledge card they acted almost like they were being deputized!”

In preparation for the Pedestrian Plan, City Fabrick and the DHHS held dozens of community events, built pop-up information kiosks, and organized walking workshops and walking audits. Ulaszewski says City Fabrick is devoted to practicing “intense civic and community engagement,” pursuing egalitarian participation and empowerment that lasts long after the designers and city planners move on to the next project. This creates an “each one teach one” ethos, giving a child who signed a yellow card pledging to clean the sidewalk in front of their home the potential to create a domino effect.

Central Long Beach is an older part of the city, with a high population of Latino and Southeast Asian residents and a mix of modest single family homes, stucco apartment complexes and strip malls. All of the targeted areas share a lack of green space and healthy food options. While the midcentury infrastructure was originally built for trains and streetcars, car use quickly bloated the width of the city’s roadways. Despite great improvements in walkability over the past decade — it was named Southern California’s most walkable city last spring — in Central Long Beach there aren’t a lot options for a pleasant stroll.

In 2009, the Long Beach DHHS identified areas of Central Long Beach where over 50 percent of households fell below the federal poverty rate and began collecting data on the neighborhood’s health needs. They gathered school fitness scores, visited and catalogued products at grocery stores and fast food restaurants, and conducted walkabilty assessments to and from every market. Their findings determined that safe walking access to healthy food was one of the residents’ most pressing needs. Rather than isolate these two issues from each other, Turnbull and her colleagues recognized that safe, walkable access was a crucial element for the overall health of Central Long Beach residents, which caused them to reach out to City Fabrick. Perhaps unusual for civic health departments, Turnbull explained that Long Beach’s DHHS promotes the idea that “walking is a public health priority.”

Ulaszewski and Turnbull knew they wanted to avoid prescribing solutions, and City Fabrick’s team of architects and designers were well aware of the shortfalls of conventional engagement strategies. “Asking the same 12 people to come to a meeting on a Thursday night is not the most effective plan,” says Ulaszewski. “Instead of asking, ‘Who’s not at the table?’ we try to ask, ‘Whose table are we not at?’”

City Fabrick embedded themselves within the broad community network established by the DHHS and collaborating nonprofits in Central Long Beach. They set up booths at health fairs and other weekly community events, and staffed tables near grocery stores, bus stops and parking lots that were already a natural part of residents’ routes, seeking ways to make talking about walking in Central Long Beach easy.

“We’ve found that If we use planning language we see people’s eyes begin to glaze. So we usually start with questions like ‘What would help you walk today? Or help you walk further?’ A good way to engage with parents is to ask: ‘How tightly do you grip your child’s hand on this street? Or do you let them walk on their own here?’” says Ulaszewski. While most people don’t know the acronym-heavy jargon of city planning, or the nuances of the term “walkability,” a parent will certainly know which streets necessitate hand holding.

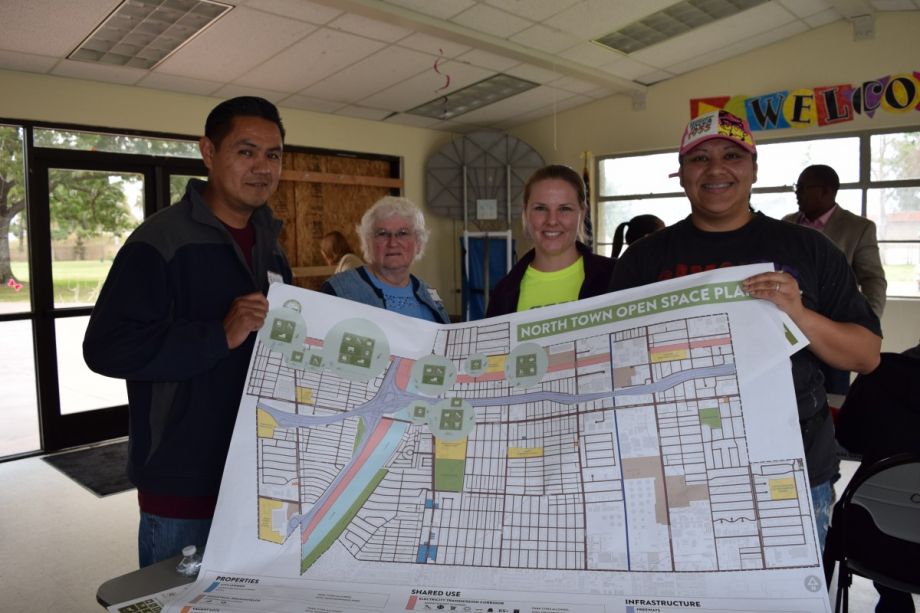

Besides listening to residents, City Fabrick led several community walks in collaboration with local stakeholders, to witness, listen and learn about local walking habits and preferences. They displayed maps and encouraged residents to mark sites of interest, including the “good, bad and ugly” parts of their neighborhood. The responses were compiled and will be turned into walking route cards that City Fabrick will return to the community and offer online for free printing. Inspired by the series of City Walk cards for major cities published by Chronicle Books, City Fabrick hopes to eventually create free cards for 50 different walks all over Long Beach. (Some of them are already available online.)

They designers also produced a DIY walking audit, offered in English, Spanish and Khmer (Long Beach has the nation’s largest Cambodian population), for residents to fill out. In an easy-to-read format, the checklist asks participants to select their priorities (safety, accessibility, beauty, etc.) and rate their walking experience to various locations (school, daycare, work, bus stops). It also asks participants why they choose not to walk to those same places. The flip side asks them to describe a place in or out of Long Beach where they enjoy walking. The data gathered was used for the Master Plan, but the residents’ experience of examining and articulating their walking environment has the potential to last much longer.

Long Beach residents weigh in on where the city needs more open spaces. (Credit: City Fabrick)

While made for Central Long Beach, these walking audits can, with slight modification, be used by anyone to evaluate their own neighborhood. In fact, City Fabrick, in partnership with California Walks, will be repurposing the checklist for an upcoming walkability survey in San Jose, California, where it will be translated into Vietnamese. The checklist is an easily distributable tool that helps residents start to notice how things like trees, visibility, streetlights, shade and sidewalks create streets that feel welcoming or dangerous.

“I see a growth in understanding in this community of how place matters, and of how their neighborhood can support a healthier lifestyle. The residents understand that we care what they think,” says Turnbull. “We’ve engaged youth a lot, who are not often engaged in this kind of thing. And they’re gaining an investment in their built environment.”

When the community response was completed, one priority was improving safety, as Turnbull and Ulaszewski had assumed, and which they address with road diets, sidewalk widening, refuge islands and continental crosswalks. But they were pleased to hear residents putting a great emphasis on having attractive places to walk for the sake of walking. So the Plan also suggests trees, public art, murals, parklets, walking loops, greenbelts and bright street furniture. Tackling obesity and diabetes through pedestrian access to healthy foods is a vital step in the right direction, but those walks need to be enjoyable, too.

The idea that walkability, and thus urban infrastructure, is a public health priority may be a crucial one for other cities considering the wellbeing of their residents. Walking could be recognized not only for its physical health benefits, but also for the mental health boost a pleasant stroll provides. “My hope is that one day doctors will prescribe walking as medicine,” says Ulaszewski. “They could say “Take three walk cards and see how you feel.”

This article is part of a Next City series focused on community-engaged design made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Lyra Kilston is a writer and 4th-generation Angeleno. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, Los Angeles Review of Books, Time, and Wired, among other publications.