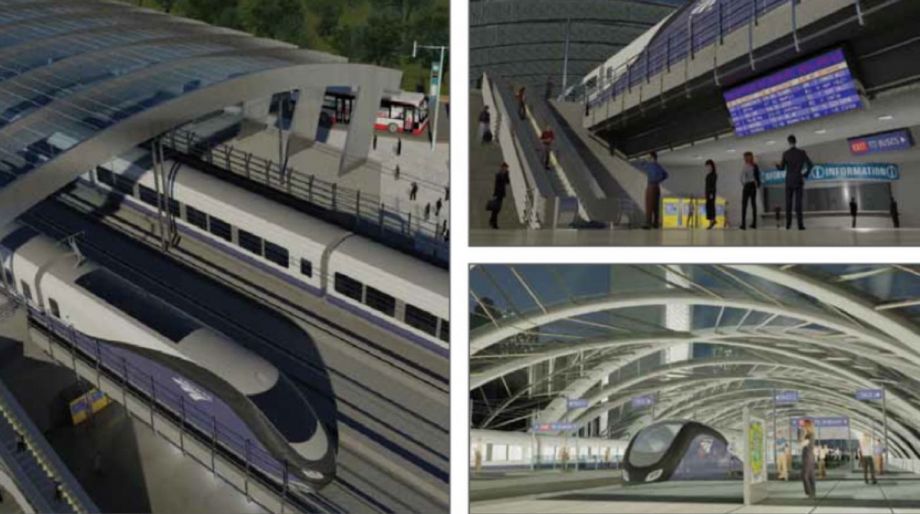

In the quite cursory report it released this week on the development of a potential high-speed rail system for the Northeast Corridor, Amtrak highlighted the potential redevelopment of two oft-forgotten cities along the route as one of the major advantages of an investment that could add up to more than $117 billion.

At the moment, there is no funding for Amtrak’s proposal, but it is the latest in a whole crop of similar plans. If the U.S. government continues to push intercity rail as a major travel mode, similar projects could be built.

Amtrak repeated what has become typical rhetoric about the advantages of high-speed rail: That the arrival of vastly improved travel times to other major cities would aid in the development of places that have been left behind by a changing economic environment. In the Northeast, that could mean restoring economic prosperity to Hartford and Baltimore, both awkwardly positioned between regional powerhouses like New York and Boston. This is the same language that has been used in reference to places like Detroit and the cities of California’s Central Valley, which may see much better rail service if their respective state governments get their way.

Whether high-speed rail provides the economic expansion Amtrak suggests it might is arguable, but excellent train service would undoubtedly make connections between currently cut-off cities much more simple. Under Amtrak’s plan, citizens of Hartford would have access to 7 million jobs within 90 minutes by rail, compared to just 1.4 million today; a similar expansion would occur for Baltimore. “These actions,” the report suggests, “would more closely tie Baltimore to the economic engine of the Northeast Corridor.” In other words, the city’s future growth would be based on its proximity to other, more healthy cities upon which it might be able to cull some benefit.

Is this the position in the national economy cities like Baltimore should be hoping for? If not, is there any alternative?

If you take Amtrak at its word, truly fast high-speed rail would encourage the growth of the Northeast region as a mega-region; by allowing commutes as quick as three and a half hours between Washington, D.C. and Boston, the whole concept of the metropolitan region is exploded. Business can be conducted across city and state lines with ease.

Here, I’ll take these assessments at face value, though in further analysis, we should endeavor to question whether mega-regions are legitimate physical manifestations of new social and economic interactions based on lowered travel times.

Ignoring that matter, the rise of the mega-region could allow capital that is freely flowing in New York and Washington to migrate (or be intentionally spread) to other cities along the corridor, like Baltimore and Hartford. In theory, people would be more likely to invest in these relatively downtrodden places if they could easily get to and from them from other cities.

But what statement does that make about the viability of these cities as independent units? Should Baltimore’s future identity just be as a second job core for Washington, and Hartford the same for New York? Does this mean a loss of local identity?

At this point, no answers to those questions have yet been established, but the experience of older suburbs brought into the social and economic realms of nearby cities suggests a possible historical model. Brookline, near Boston, and Hoboken, near New York, are interesting examples; both were formed as independent cities with most people living within them staying there to work. Yet as improved and fast transportation links were developed, first in the form of streetcars and mainline rail, and then in the form of highways, these cities turned into suburbs, converting them from independent entities into functional units of a growing metropolitan region. If they once had truly local economic and social identities, those have been mostly replaced by a regional identity focused on the core city.

Can — or should — Baltimore and Hartford expect to do they same? Is the future of a troubled city simply to be subsumed into the orbit of another, more powerful one? Even if the answer is no, there may be no other choice for such cities; they are stuck in an economic rut from which they must find a way out. According to the same Amtrak document, Hartford employment declined 42% between 1970 and 1998. Those dismal facts may not be resolved by anything other than closer connections to other, better-off cities.

Yonah Freemark is a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center at the Urban Institute, where he is the research director of the Land Use Lab at Urban. His research focuses on the intersection of land use, affordable housing, transportation, and governance.