Held in Tokyo in 1964, the 18th Olympic Games were a showcase of Japan’s rising economic and industrial strength in the aftermath of World War II. It was a pivotal moment for the city. Less than 20 years after being decimated by the Allied firebombing, Tokyo had rebounded with a dazzling array of cutting-edge technology and infrastructure. The world’s first bullet train zipped spectators between Osaka and the capital at an unprecedented 130 miles per hour, and a monorail and a new expressway (considered pinnacles of 1960s urban mobility) moved people throughout the city. The first trans-Pacific communications cable was laid from Japan to Hawaii just in time for the Games. It was even the first Olympics to use computers instead of stopwatches.

This infrastructure — all created in the run-up to the ‘64 Games — “formed the foundation for Tokyo’s current prosperity,” wrote one official from the city’s bureau of construction in a 2012 article titled, “Realization of a Safe City Against Disasters in Tokyo.”

Two years ago, it was announced that in 2020, Tokyo will host the Olympic Games once again. But it seems that in the 56 years since the city’s last Olympics, optimism and ambition has been replaced with pragmatism and fear. The change in tone was palpable in an interview Tokyo’s 65-year-old governor, Yochi Masuzoe, gave to Reuters in February. “There are so many challenges [leading up to 2020], but my highest priority is the possibility of a disaster,” said Masuzoe. “We have already begun so as to have the perfect disaster prevention and mitigation plan.”

While the ’64 Games was a chance for Japan to show how it had advanced as a burgeoning world power, Tokyo will use the 2020 Games to display its preparedness for a natural disaster. As one of the most dangerous metropolitan areas in the world, the city sets the bar for how mega-cities should integrate disaster mitigation into their plans for large global events. But this focus is also about quelling fears — foreign visitors will no doubt be skittish with thoughts of the ongoing Fukushima nuclear crisis and the devastating destruction caused by the tsunami in March 2011.

What’s interesting is that, although natural disasters are clearly more of a focus this time around, they were just as prevalent half a century ago, even if they were spoken of less. Four months before the Olympics were set to begin in 1964, a magnitude 8.0 earthquake struck the northern Japanese city of Niigata, killing 25, damaging almost 2,000 homes and toppling an apartment block. Hirosi Kawasumi from the Earthquake Research Institute at the University of Tokyo wrote about the quake in 1968: “Even the Japanese themselves shuddered when they thought of the potential calamity of an earthquake that could strike when the Olympic stadiums were full of spectators.”

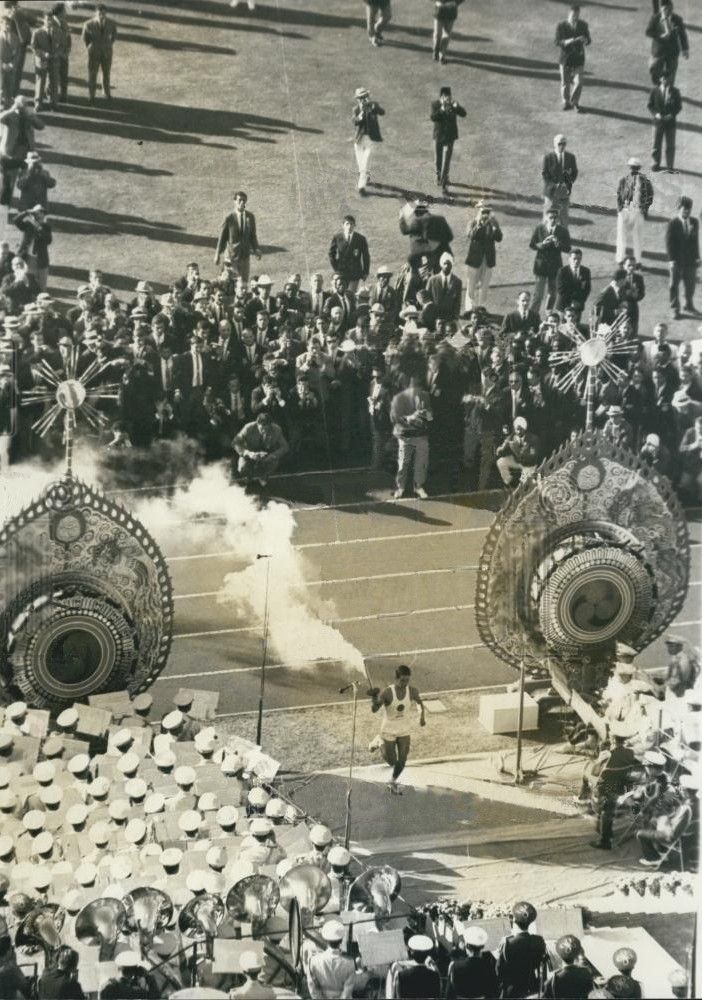

A runner carries the torch for the 1964 Games in Tokyo. Photo credit: Wikipedia

But shuddering didn’t turn into budgeting for a comprehensive mitigation plan. Most money for public works in the mid ‘60s went toward flood control (this was the dam-building decade, after all) or “infrastructure projects … directly related to the games themselves, and visitor access,” writes Roman Cybriwsky in his book Historical Dictionary of Tokyo. “When Tokyo prepared for the [Olympics], it paid little attention to comprehensive planning for the city as a whole.”

Today, as it preps for 2020, Tokyo is clearly considering the city as a whole. Its disaster prevention plan is based on a report titled “Tokyo Vision 2020: Driving change in Japan/Showing our best to the world.” It’s an eight-goal strategy that Japan hopes can be implemented before the Games, and works from a comprehensive template that the report calls “sophisticated disaster resistance.” Three-year “action programs” break the goals down into manageable projects. For example, the action program taking place now (2013-2015) involves 22 policies and 363 projects requiring a budget of approximately 2.7 trillion Yen ($26.5 billion). That money will help fund a “complete seismic retrofit of buildings alongside emergency transport roads,” a wider retrofit across the city and the construction of wider roads in the 17,300 acres of the city made up of close-set wooden houses.

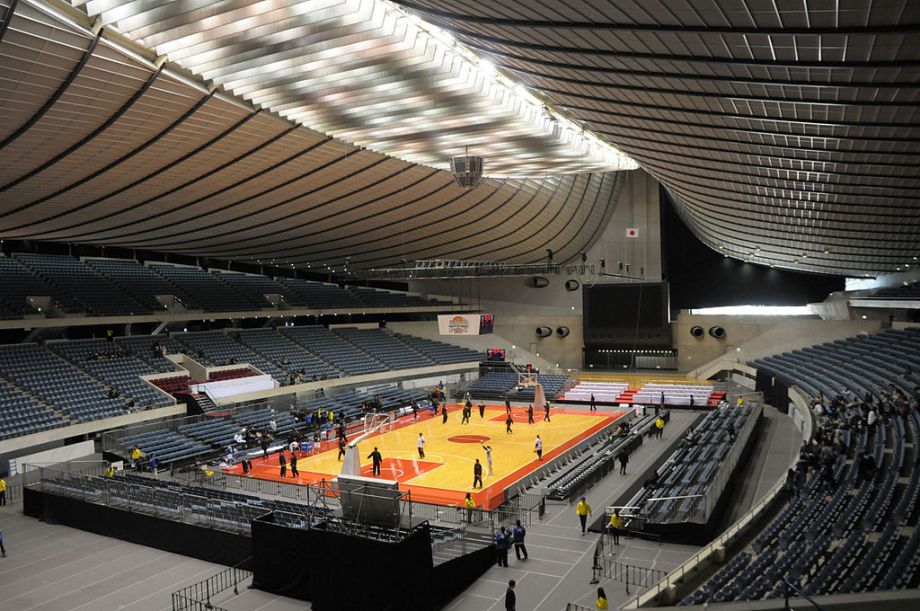

One major structure marked for retrofitting is the Yoyogi National Stadium, the main site for the ‘64 Olympic Games designed by Kenzō Tange. It may be old, but its temple-inspired form is still commanding. A new stadium, designed by London-based Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, will be part of this retrofitting, giving a new face to the old stadium. It will be the most expensive stadium in the world (if it is built).

Incredible amounts of money are being doled out by the government at a local and national levels with the hope of expanding infrastructure spending, and raising the wages of construction workers in the process. This kind of spending is something Japan excels at — it’s often seen as a panacea to the country’s economic woes. “The health of the Japanese economy is important,” said Governor Masuzoe in his February interview with Reuters. “We have come out of the recession and this economic growth is very important and as governor I want to sustain this momentum.”

But for those looking further ahead, mitigation will not occur by massive public-works projects alone. Tokyo will always be in the shadow of natural disasters, but there are other threats already knocking on the city’s door. Japan needs to “restrict new construction of infrastructure and focus on maintaining and renewing existing facilities to meet demographic changes,” says former prime minister Morihiro Hosokawa, reported in an Asahi Shimbun article published earlier this year. It’s possible that by 2020, that declining population we’ve been hearing about might finally start to be felt in Tokyo. Indeed, it’s possible that the city’s two Olympic Games may end up serving as bookends to Japan’s “miracle” rise to power and unrestrained growth. But there’s always hope — a lot can change in six years.

_1200_700_s_c1_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)