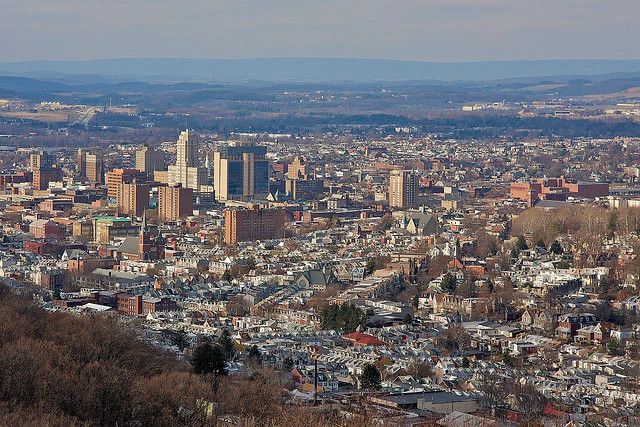

If you have heard of Reading, Pa., it’s probably because at some point during a meandering game of Monopoly you landed on the Reading Railroad. But two years ago, the city of 88,000 that lies 50 miles northwest of Philadelphia earned a much different reputation: It became the U.S. city with the largest share of its residents living in poverty.

Compiled from Census Bureau data, the list included only cities with populations of 65,000 or more. A whopping poverty rate of 41.3 percent put Reading ahead of more famously poor places like Detroit and Camden, N.J., and earned national media coverage from the likes of the New York Times and NPR. (New data released last week puts Detroit at the top of the most-impoverished list, with Reading second, at 40.5 percent of its residents now living in poverty.)

For decades — since the early 20th century, at least — Reading has been a shadow of its former, bustling self. But its descent into truly dire conditions happened rapidly. It went from having the 32nd highest poverty rate in the country to the highest in just 10 years. Employment rates fell by about 10 percent between 2000 and 2010, and a substantial number of those losses were low-skill jobs.

In response, the city and its economic development organizations have made the expected efforts to entice businesses to Reading. So far this year, the Greater Reading Economic Partnership (GREP), a public-private non-profit, has fielded inquiries from about 15 businesses looking to the area as a potential home. Seven of those businesses are in the manufacturing sector. But according to GREP president and CEO Jon Scott, everyone has the same question: “Will there be enough people available to fill the needs in the workforce?”

In 2009 and 2010, GREP surveyed 96 local businesses and found that 47 percent of them identified lack of skills as a workforce problem. Of those, 26 percent specifically noted a lack of technical skills. “We kept hearing from local employers, especially manufacturers, that they have not been able to find enough people with the right kind of trade skills and vocational degrees and certificates to meet the demands of the job market,” Scott said. “So the question was, what’s causing the disconnect?”

The answer was that people weren’t choosing an educational path that would lead to available openings. Reading needed its residents learning the skills that could land them jobs, a conundrum debated in cities nationwide (and the topic of this week’s Forefront story).

An early effort to address this problem was the Technical Academy, a partnership between the local community college and the two technology centers that train high school students. By the time students graduate high school, they can have up to 27 credits of the 75 needed to receive an associate degree under their belts.

“There are more ways to go to college” than the usual B.A.-after-high school path, said Gerald Witmer, administrative director of the Reading Muhlenberg Career & Technology Center. And not only that, but “there are ways to go to college and get someone else to pay for it.” There’s no tuition for Technical Academy college credits, and many manufacturing companies help cover tuition for employees’ continuing education.

With job opportunities available and technical training programs ramped up, Witmer said, one considerable obstacle remains: The “stigma of what people envision as the manufacturing workplace.” Today it’s just as common to see manufacturing employees in lab coats, sitting at computers, as assembling objects with machinery. These are not the filthy, stifling factories that “people see if they watch the History Channel,” Witmer explained.

It turned out that the most important strategy for connecting people to available jobs was to get across what “manufacturing” means in a world of 3-D printing and other advanced technologies. In other words, manufacturing needed a rebranding.

Enter Careers in 2 Years, GREP’s marketing campaign aimed at changing negative perceptions about manufacturing while touting the advantages of attending local career and technology centers. These take less time and cost less money than a four-year degree, and the resulting jobs pay well and are immediately available with many companies.

A central aim was to “get the salaries out there,” said Matt Golden, managing partner at Reese, the advertising agency that designed the campaign. “We wanted to present vocational training as a cool option that was very viable with good salaries.”

The Careers in 2 Years website promotes welding, mechatronics, robotics, computerized drafting and other careers that used to fall under the heading “vo-tech.” Besides an online presence, the campaign has included 30-second spots on local cable stations, a video shown during movie theater previews, outdoor ads, fliers used for direct mailing and handouts, and newspaper ads.

What Golden didn’t anticipate was the amount of conversation the campaign would generate among agencies looking to promote the same career tracks in other cities. He regularly gets inquiries asking what it would take to develop similar campaigns elsewhere. “Now,” Golden said, “they have something tangible” to consider implementing — if financing were available.

The cost, according to Scott, was “more than six figures” over the course of a few years, mostly funded out of GREP’s budget and helped by two grants from the Berks County Community Foundation, plus ad placement donations from cable companies and outdoor advertising companies. The fight is against the belief that only baccalaureate-level degrees, whatever the field, should be a person’s goal. Scott noted that the campaign targets not only students but also their parents.

At the Reading Muhlenberg Career & Technology Center, Witmer’s staff members use the Careers in 2 Years materials for recruiting, which they do as early as eighth and ninth grades. He sees the Careers in 2 Years campaign as the marketing piece of a local workforce puzzle. “We take that piece,” Widmer said, “and take it to the level of ‘let’s sit down and really talk about this.’”

Theresa Everline is a Philadelphia-based freelancer who likes to write about arts, urban issues and fascinating people. Formerly the editor-in-chief of Philadelphia City Paper, she has contributed stories to the New York Times, the “Ideas” section of the Boston Globe, SmartPlanet.com and Preservation Online. See her work at theresaeverline.com.